Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Garden Party (Fête Champêtre), 1725–30, and The Bathers, 1728–30,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.326.5407.

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Garden Party (Fête Champêtre), 1725–30, and The Bathers, 1728–30,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.326.5407.

Jean-Baptiste Pater is one of the more enigmatic painters of the early eighteenth century. Often overshadowed by his teacher Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684–1721), he has historically been dismissed as a painter whose work lacked originality and adhered too closely to his master’s example. Yet two paintings by Pater in the collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art—The Garden Party (Fête Champêtre) and The Bathers—invite a reassessment. Painted around 1725–30, these works capture a critical juncture in Pater’s brief career when he moved from Watteau’s visual lexicon of elegant leisure toward more erotically charged subjects. Although the two paintings are often considered pendantspendant: One of two paintings conceived as a pair and intended to be displayed togther. due to their nearly identical dimensions and shared provenance since at least 1889, they diverge sharply in subject, tone, and paint handling. Taken together, they offer a compelling window into the tension between civility and sensuality in Pater’s oeuvre, while exemplifying how his reuse of motifs and passages reflects a pragmatic, commercially savvy response to market demands—one that aligns with broader eighteenth-century practices of recombination and replication.1In a recent publication, David Pullins redefines eighteenth-century French painting by showing how artists such as Watteau, Jean-Baptiste Oudry (1686–1755), and François Boucher (1703–1770) relied on a “cut-and-paste” approach, in which motifs circulated freely across media, contexts, and collaborative studios—a model that also illuminates Pater’s practice. See David Pullins, The Mobile Image from Watteau to Boucher (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2024), esp. 95, in which the author discusses the idea of recycling and collaboration, positing that the redeployment of motifs and the imitation of extant passages originated by other artists constituted a practical solution to commercial demands rather than an erudite citation.

Pater was Watteau’s only documented pupil.2Pater initially studied with a local painter and then with his father, who was a sculptor, before working briefly under Watteau in Paris. The only catalogue raisonné and substantive account of Pater’s life remains Florence Ingersoll-Smouse, Jean-Baptiste Joseph Pater: Biographie et catalogue critiques, l’œuvre complète de l’artiste (Paris: Les Beaux-arts, 1928). Both artists hailed from

Valenciennes, and Pater likely first encountered Watteau around 1710. A

short-lived apprenticeship ended in a falling out, prompting Pater to

return to Valenciennes before reestablishing himself in Paris by 1718,

where he worked for, among others, Watteau’s dealer Edme-François

Gersaint. In the final months of Watteau’s life, the two reconciled, and

Pater later acknowledged that the brief time spent with his mentor had a

formative impact on his artistic development. After Watteau’s death in

1721, Pater devoted himself to supplying fêtes galantes—idealized

visions of courtly leisure or amorous play—to meet a market eager for

the genre. He was agréé (agreed, or admitted) by the Académie Royale

in 1725 and reçu (received) in 1728 as a painter of fêtes galantes

with his painting Soldier’s Merrymaking (Musée du Louvre), one of the

few firmly datable works in his oeuvre.3For Pater’s morceau de reception (reception piece), see Jean-Baptiste Pater, Une Fête Champêtre: Réjouissance de Soldats, 1728, oil on canvas, 44 7/8 x 60 5/8 in. (114 x 154 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. 7137, https://collections.louvre.fr

The Garden Party exemplifies Pater’s engagement with the fête galante

tradition pioneered by Watteau. Set in a clearing on the wooded edge of

a park, the painting depicts elegantly dressed couples reclining,

conversing, and exchanging flirtatious glances as they enjoy

refreshments. Some lean toward one another and others feign resistance,

while children play at their feet. The verdant setting, the rhythmic

grouping of figures, and several specific motifs—including the African

servant, the seated man with his knees apart, and the child viewed from

behind—quote directly from Watteau’s visual vocabulary.4Richard Rand noted this in his catalogue entry for this pair of paintings in Intimate Encounters: Love and Domesticity in Eighteenth-Century France, exh. cat. (Hanover, NH: Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, 1997), 101–3. The couple

at far left, dressed in seventeenth-century Flemish attire, show that,

like Watteau, Pater also drew inspiration from Flemish art, notably the

work of Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640).5See, in particular, Peter Paul Rubens, Rubens, Helena Fourment (1614–1673), and Their Son Frans (1633–1678), ca. 1635, oil on wood, 80 1/4 x 62 1/4 in. (203.8 x 158.1 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1981.238, https://www.metmuseum.org

Costume amplifies this theatricality. The women are clothed in

fashionable silk gowns of the period, while the men wear

pseudo-historical or masquerade garments evocative of the

Comédie-ItalienneComédie-Italienne: The French term for Italian commedia dell’arte companies who performed in France. Coined in 1680, it was intended to distinguish Italian plays from native French plays. The Comédie-Italianne was expelled from Paris in 1697 but permitted to return in 1716. See commedia dell’arte.. This shift between contemporary and theatrical dress,

inherited from Watteau, heightens the sense of artifice and frames the

scene as a carefully choreographed fantasy. The sculpture of a reclining

female nude, presiding over the assembly from atop a monumental urn,

could evoke the mythic presence of Venus, representing the idea of

sensual love, in contrast to the more civilized amorous interactions

taking place below.7I am grateful to Yuriko Jackall, who offered this suggestion via email on July 18, 2024. Jackall suggested it reminded her of the reclining stone statue in the background of Antoine Watteau, Les Champs Elisées, ca. 1720–21, oil on walnut panel, 12 1/4 x 16 1/8 in. (31.2 x 41 cm), Wallace Collection, London, P389, https://wallacelive.wallacecollection.org:443

Fig. 2. Claude Audran III, La Magnificence Royale, 1729, oil on canvas, 84 5/8 x 84 5/8 in. (215 x 215 cm), Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, inv. no. MV8778. Photo: Christophe Fouin © RMN-Grand Palais / Christophe Fouin / Art Resource, NY

Fig. 2. Claude Audran III, La Magnificence Royale, 1729, oil on canvas, 84 5/8 x 84 5/8 in. (215 x 215 cm), Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, inv. no. MV8778. Photo: Christophe Fouin © RMN-Grand Palais / Christophe Fouin / Art Resource, NY

Fig. 3. Attributed to Jean-Baptiste Pater, Rococo Wall Design with a Fountain and Swans [verso], ca. 1729, red chalk and red chalk counterproof on two joined sheets of laid paper, sheet: 9 x 9 1/8 in. (22.9 x 23.2 cm), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 1996.25.1.b

Fig. 3. Attributed to Jean-Baptiste Pater, Rococo Wall Design with a Fountain and Swans [verso], ca. 1729, red chalk and red chalk counterproof on two joined sheets of laid paper, sheet: 9 x 9 1/8 in. (22.9 x 23.2 cm), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 1996.25.1.b

Pater’s link to this ornamental tradition was more than incidental. Like Watteau, Pater also worked in Audran’s workshop, supplying both arabesque decoration and figure designs.9Pullins, Mobile Image, 51, 56. The younger artist absorbed a visual system in which motifs could migrate fluidly between fine and decorative arts, as seen in a recto/verso drawing featuring a design for a RococoRococo: Developed under the reign of Louis XV (r. 1715–74) and his mistress the Marquise de Pompadour (1721–64), the Rococo style featured sensual, pastoral, and mythological subjects set in silvery light and created in painterly, soft colors. The works of François Boucher epitomize the style that spread to every medium, including furniture and decorative arts. wall with a fountain, swans, and a male figure holding a staff (Fig. 3). Like Watteau, Pater used red chalk for his preparatory drawings, which often contained multiple figure types or ornamental elements awaiting placement: to be inserted, recombined, or altered as needed for a commission. David Pullins has argued that this modular approach allowed artists to build up or break down their compositions with ease.10Pullins, Mobile Image, 99. Figure studies functioned as visual currency—reentering compositions in different guises, whether destined for a decorative panel, a cabinet picture, or an easel painting. In the case of The Garden Party, for instance, a drawing of two women seen from complementary vantage points (Fig. 4) finds visual echoes in the seated young girls facing opposite directions, underscoring the mobility and reuse of figural templates in Pater’s repertoire.11There is no definitive catalogue raisonnée of Pater’s drawings.

Fig. 4. Jean-Baptiste Pater, Two Seated Ladies, ca. 1720–30, red chalk, 5 5/8 x 9 in. (14.2 x 23 cm), Collection Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands, inv. no. FI 151 (PK). On loan from the Stichting Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen (former Koenigs collection) / Photo: Studio Tromp

Fig. 4. Jean-Baptiste Pater, Two Seated Ladies, ca. 1720–30, red chalk, 5 5/8 x 9 in. (14.2 x 23 cm), Collection Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands, inv. no. FI 151 (PK). On loan from the Stichting Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen (former Koenigs collection) / Photo: Studio Tromp

Fig. 5. Jean-Antoine Watteau, Three Studies of a Young Black Man, ca. 1717, black, red, and white chalk and wash, 9 5/8 x 10 5/8 in. (24.3 x 27 cm), Musée du Louvre, inv. no. RF 28721, Recto. Photo: Suzanne Nagy. © Musée du Louvre, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Suzanne Nagy / Art Resource, NY

Fig. 5. Jean-Antoine Watteau, Three Studies of a Young Black Man, ca. 1717, black, red, and white chalk and wash, 9 5/8 x 10 5/8 in. (24.3 x 27 cm), Musée du Louvre, inv. no. RF 28721, Recto. Photo: Suzanne Nagy. © Musée du Louvre, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Suzanne Nagy / Art Resource, NY

The turbaned African servant at right is a recurrent motif in art from

the seventeenth century into the eighteenth.12The motif of the exoticized Black figure in art has many seventeenth-century precedents, deftly unpacked in Judy Sund, “Middleman: Antoine Watteau and ‘Les Charmes de La Vie,’” Art Bulletin 91, no. 1 (2009): 59–82. Watteau’s Three

Studies of a Young Black Man (Fig. 5) provide a prototype for several

of Pater’s fête galante figures; Pater likely had access to the same

sitter or to Watteau’s studies.13See, in particular, Jean Antoine Watteau, La Conversation, 1712–13, oil on canvas, 19 3/4 x 24 in. (50.2 x 61 cm), Toledo Museum of Art, 1971.152, https://emuseum.toledomuseum.org

If The Garden Party engages with the theatrical decorum of the fête

galante, The Bathers moves into more explicitly erotic territory. A

group of women in various states of undress frolic around a shallow pool

in a secluded glade. On the left, a sculptural group of two cupids

riding a dolphin, an emblem of Venus, crowns the baroque fountain that

feeds the pool; at right, a stone pavilion closes the space. At the

composition’s center, a bather with her back to the viewer climbs from

the water, her chemisechemise: A plain, thin white cotton garment with short sleeves and sometimes a low neckline. soaked and clinging—a pose Pater reused in

multiple bathing scenes, including versions in the Rosenberg Collection

(Fig. 6) and others.17See Ingersoll-Smouse, Jean-Baptiste Joseph Pater, figs. 83, 86, 88, 89, 97–98, and 102, pp. 44–46, 144, 146–48, 153, 157. Technical examination of the Kansas City

painting shows that this figure’s drapery was originally shorter and

more revealing, likely lengthened in the early nineteenth century for

reasons of modesty (Fig. 29).18See accompanying technical entry by paintings conservator Diana M. Jaskierny, “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Bathers, 1728–30,” https://doi.org

This male spectator in The Bathers recalls the Greek myth of Diana and

Actaeon—in which Actaeon spies on Diana’s nymphs as they bathe—reframed

here as a secular, libertine fantasy where secluded female spaces become

spectacles for male (and, by extension, the viewer’s) gaze.19Ingersoll-Smouse has proposed that Pater’s bather scenes may have been commissioned by members of libertine societies or cénacles galants (gallant gatherings), aristocratic circles devoted to wit, sensuality, and unorthodox pleasures. See Ingersoll-Smouse, Jean-Baptiste Joseph Pater, 14. Pater’s

approach is relatively restrained: only one woman is topless, while

others reveal their bodies through wet drapery or partial undress. This

contrasts with Watteau’s Diana at Her Bath (Musée du Louvre), where

the mythological context legitimizes full nudity, and the famously

chaste goddess is alone.20See Antoine Watteau, Diana at Her Bath, 1715/16, oil on canvas, 31 1/2 x 39 3/4 in. (80 x 101 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, https://collections.louvre.fr

Both The Garden Party and The Bathers reflect an ideal of elite leisure in the 1720s and early 1730s, projecting aristocratic pleasure onto a fictional countryside that stages the rituals of conversation, seduction, and repose. Although they are linked in ownership, format, and certain compositional devices—for example, the matching cylindrical plinths at right that serve as beverage stations—the two paintings differ markedly in mood and theme. The Garden Party is public, performative, and rooted in codes of elite sociability; The Bathers, by contrast, plays more overtly to erotic fantasy, with its secluded setting, voyeuristic premise, and subtle cues of social mixing. The presence of both refined and rustic dress hints at a licentious pastoral ideal; one that blurs class boundaries for sensual effect. Their juxtaposition reflects the breadth of Pater’s range and the adaptability of his compositional vocabulary. As Martin Eidelberg has observed, eighteenth-century interiors often paired dissimilar subjects for visual and conversational variety, and it is plausible that the Kansas City pair was acquired with such a display in mind.21In an email exchange with the author (August 8, 2024), Martin Eidelberg explained that the pairing of two dissimilar themes was not at all unusual for the period.

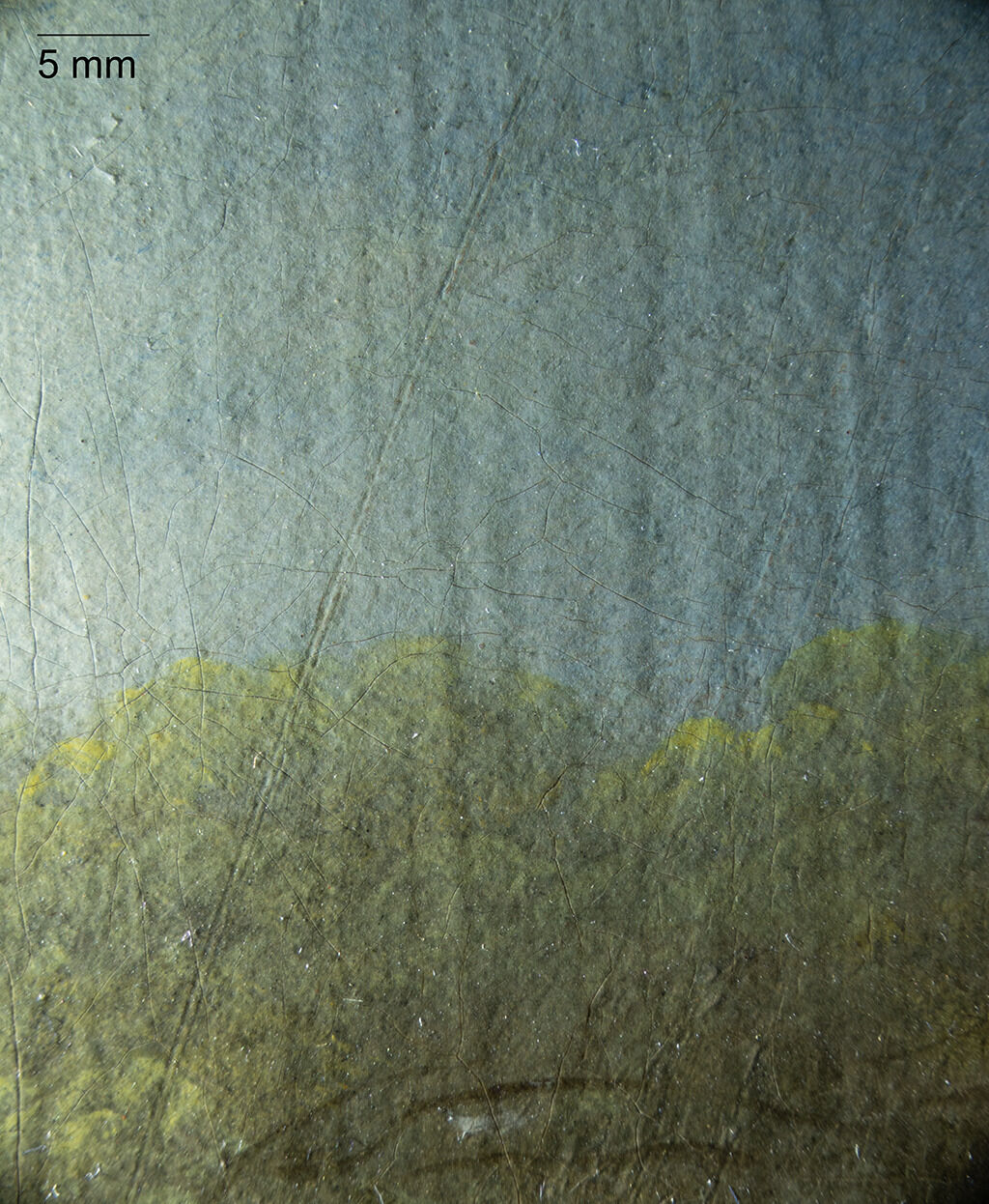

The two paintings also diverge stylistically. The palette of The Bathers

is cooler than that of The Garden Party, the brushwork

sketchier, and the forms more atmospheric. While dating Pater’s works is

notoriously difficult, such handling supports a slightly later date for

The Bathers. Unless one counts the overdoor at the Petit Trianon in

Versailles (ca. 1720; Fig. 7), whose tone and treatment are markedly

different from The Bathers, Pater seems not to have engaged with

bathing subjects until around 1728–29.22This overdoor painting from the dining room of the Petit Trianon, commissioned by Louis XV, is one of Pater’s earliest known works. It had previously been attributed to Watteau on stylistic grounds. See the object entry in the collections database, “Le Bain,” POP: la plateforme ouverte du patrimoine, Ministère de la Culture, updated February 8, 2024, https://pop.culture.gouv.fr

In both works, Pater’s reuse of motifs—whether drawn from Watteau, from his own earlier compositions, or from ornamental design—signals his participation in a broader eighteenth-century visual economy. As Pullins has recently argued, this “cut and paste modality” was not merely a workaround for productivity but a well-established mode of invention shaped by workshop practice, collector preference, and commercial demand.23Pullins, Mobile Image, 1. Figures, poses, and groupings circulated freely among easel painting, decorative arts, and ornamental prints, with artists often extracting studies from albums for reuse. Rather than aiming for originality in the modern sense, painters like Pater calibrated familiarity and novelty to suit a market that valued variation within recognizable forms.

Pater’s ability to recontextualize familiar motifs for new emotional registers—whether the composed elegance of The Garden Party or the sensual intimacy of The Bathers—demonstrates not only artistic dexterity but also commercial acumen. His prodigious output in these years was likely fueled as much by personal urgency as by external demand, and his strategic recycling of imagery reflects a studio practice attuned to the expectations of collectors and dealers. Positioned between civility and seduction, tradition and adaptation, Pater’s paintings speak to a period culture that prized pleasure and recognition as much as innovation.

Notes

-

In a recent publication, David Pullins redefines eighteenth-century French painting by showing how artists such as Watteau, Jean-Baptiste Oudry (1686–1755), and François Boucher (1703–1770) relied on a “cut-and-paste” approach, in which motifs circulated freely across media, contexts, and collaborative studios—a model that also illuminates Pater’s practice. See David Pullins, The Mobile Image from Watteau to Boucher (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2024), esp. 95, in which the author discusses the idea of recycling and collaboration, positing that the redeployment of motifs and the imitation of extant passages originated by other artists constituted a practical solution to commercial demands rather than an erudite citation.

-

Pater initially studied with a local painter and then with his father, who was a sculptor, before working briefly under Watteau in Paris. The only catalogue raisonné and substantive account of Pater’s life remains Florence Ingersoll-Smouse, Jean-Baptiste Joseph Pater: Biographie et catalogue critiques, l’œuvre complète de l’artiste (Paris: Les Beaux-arts, 1928).

-

For Pater’s morceau de reception (reception piece), see Jean-Baptiste Pater, Une Fête Champêtre: Réjouissance de Soldats, 1728, oil on canvas, 44 7/8 x 60 5/8 in. (114 x 154 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. 7137, https://collections.louvre.fr

/ark: ./53355 /cl010061409 -

Richard Rand noted this in his catalogue entry for this pair of paintings in Intimate Encounters: Love and Domesticity in Eighteenth-Century France, exh. cat. (Hanover, NH: Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, 1997), 101–3.

-

See, in particular, Peter Paul Rubens, Rubens, Helena Fourment (1614–1673), and Their Son Frans (1633–1678), ca. 1635, oil on wood, 80 1/4 x 62 1/4 in. (203.8 x 158.1 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1981.238, https://www.metmuseum.org

/art ./collection /search /437532 -

Christoph Vogtherr has observed: “A pattern emerged that, for Pater, almost exclusively drawings of individual figures, mostly from the immediate foreground of his compositions, can be identified, but so far no composition drawings.” Vogtherr suggests that Pater would take a single motif here and there and insert it into a composition, thus creating something new. See Christoph Vogtherr et al., Französische Gemälde I: Watteau, Pater, Lancret, Lajoüe (Berlin: Akademie, 2011), 245–47.

-

I am grateful to Yuriko Jackall, who offered this suggestion via email on July 18, 2024. Jackall suggested it reminded her of the reclining stone statue in the background of Antoine Watteau, Les Champs Elisées, ca. 1720–21, oil on walnut panel, 12 1/4 x 16 1/8 in. (31.2 x 41 cm), Wallace Collection, London, P389, https://wallacelive.wallacecollection.org:443

/eMP ./eMuseumPlus ?service =ExternalInterface&module =collection&objectId =65323&viewType =detailView -

I am grateful to Christoph Martin Vogtherr, who offered this suggestion via email on August 18, 2024. For examples of this type of ornamental design, see Jean Berain, engraved by Gérard Jean-Baptiste Scotin (1698–after 1755) and others, Ornament Designs Invented by J. Berain, 1711 or after, engraving, 20 5/16 x 16 in. (51.6 x 40.6 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 21.36.141, https://www.metmuseum.org

/art ./collection /search /345898 -

Pullins, Mobile Image, 51, 56.

-

Pullins, Mobile Image, 99.

-

There is no definitive catalogue raisonnée of Pater’s drawings.

-

The motif of the exoticized Black figure in art has many seventeenth-century precedents, deftly unpacked in Judy Sund, “Middleman: Antoine Watteau and ‘Les Charmes de La Vie,’” Art Bulletin 91, no. 1 (2009): 59–82.

-

See, in particular, Jean Antoine Watteau, La Conversation, 1712–13, oil on canvas, 19 3/4 x 24 in. (50.2 x 61 cm), Toledo Museum of Art, 1971.152, https://emuseum.toledomuseum.org

/objects ./55384 /la-conversation -

See Sund, “Middleman,” 66–76. See also David Pullins, “Watteau’s Black Models,” in Univers de Watteau: Résaux et influence autour d’Antoine Watteau (1684–1721), ed. Alex Moulnier (Paris: L’Échelle de Jacob, 2022), 183–89.

-

See Ingersoll-Smouse, Jean-Baptiste Joseph Pater, nos. 29, 30, 40, 41, 51, 200bis, pp. 241, 474, 506, 558, 561, 604. Pullins also makes this observation in “Watteau’s Black Models,” 189.

-

See Adrienne L. Childs, “Sugarboxes and Blackamoors: Ornamental Blackness in Early Meissen Porcelain,” in Michael E.Yonan and Alden Cavanagh, eds., The Cultural Aesthetics of Eighteenth-Century Porcelain (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2010), 159–77; and Childs, “A Blackamoor’s Progress: The Ornamental Black Body in European Furniture,” in Awam Amkpa, ed., ReSignifications: European Blackamoors, Africana Readings (Rome: Postcart SRL, 2017), 116–26, cited in Pullins, “Watteau’s Black Models,” 189n40.

-

See Ingersoll-Smouse, Jean-Baptiste Joseph Pater, figs. 83, 86, 88, 89, 97–98, and 102, pp. 44–46, 144, 146–48, 153, 157.

-

See accompanying technical entry by paintings conservator Diana M. Jaskierny, “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Bathers, 1728–30,” https://doi.org

/10.37764/78973 ..5 .327 .2088 -

Ingersoll-Smouse has proposed that Pater’s bather scenes may have been commissioned by members of libertine societies or cénacles galants (gallant gatherings), aristocratic circles devoted to wit, sensuality, and unorthodox pleasures. See Ingersoll-Smouse, Jean-Baptiste Joseph Pater, 14.

-

See Antoine Watteau, Diana at Her Bath, 1715/16, oil on canvas, 31 1/2 x 39 3/4 in. (80 x 101 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, https://collections.louvre.fr

/ark: ./53355 /cl010066605 -

In an email exchange with the author (August 8, 2024), Martin Eidelberg explained that the pairing of two dissimilar themes was not at all unusual for the period.

-

This overdoor painting from the dining room of the Petit Trianon, commissioned by Louis XV, is one of Pater’s earliest known works. It had previously been attributed to Watteau on stylistic grounds. See the object entry in the collections database, “Le Bain,” POP: la plateforme ouverte du patrimoine, Ministère de la Culture, updated February 8, 2024, https://pop.culture.gouv.fr

/notice ./joconde /000PE006535 -

Pullins, Mobile Image, 1.

Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Garden Party, 1725–30

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Diana M. Jaskierny, “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Garden Party (Fête Champêtre), 1725–30,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.326.2088.

MLA:

Jaskierny, Diana M. “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Garden Party (Fête Champêtre), 1725–30,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.326.2088.

The Garden Party (Fête Champêtre), painted by Jean-Baptiste Pater, demonstrates the artist’s combination of fine detail and active brushwork. In the painting, groups of figures interact dynamically. They wear rich fabric, both in color and texture, which contrasts with the soft, diffuse background.

Attached to a five-member stretcherstretcher: A wooden structure to which the painting’s canvas is attached. Unlike strainers, stretchers can be expanded slightly at the joints to improve canvas tension and avoid sagging due to humidity changes or aging., the painting appears to have been executed on a twill-weavetwill weave: A canvas weave in which one weft thread passes over one or more warp threads before passing under two or more warp threads, creating a pronounced diagonal pattern. canvas; however, weave interferenceweave interference: A distortion that can occur when excess heat or pressure is applied to a painting, usually during the lining process. As a result, the original canvas weave texture becomes more pronounced or the weave texture of the lining material becomes visible on the painting surface. Also called weave emphasis or weave accentuation. from an early lininglining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive. has complicated positively identifying the canvas weave. Although the tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. are no longer extant, likely removed during the lining process, cuspingcusping: A scalloped pattern along the canvas edges that relates to how the canvas was stretched. Primary cusping reveals where tacks secured the canvas to the support while the ground layer was applied. Secondary cusping can form when a pre-primed canvas is re-stretched by the artist prior to painting. along the top, left, and right sides indicates that the painting retains approximately its original dimensions.1The picture plane was increased between three and five millimeters on the top, bottom, and right edges during the lining process and approximately ten centimeters on the left edge near the top. Muted pink fill material and retouching covers the expanded space.

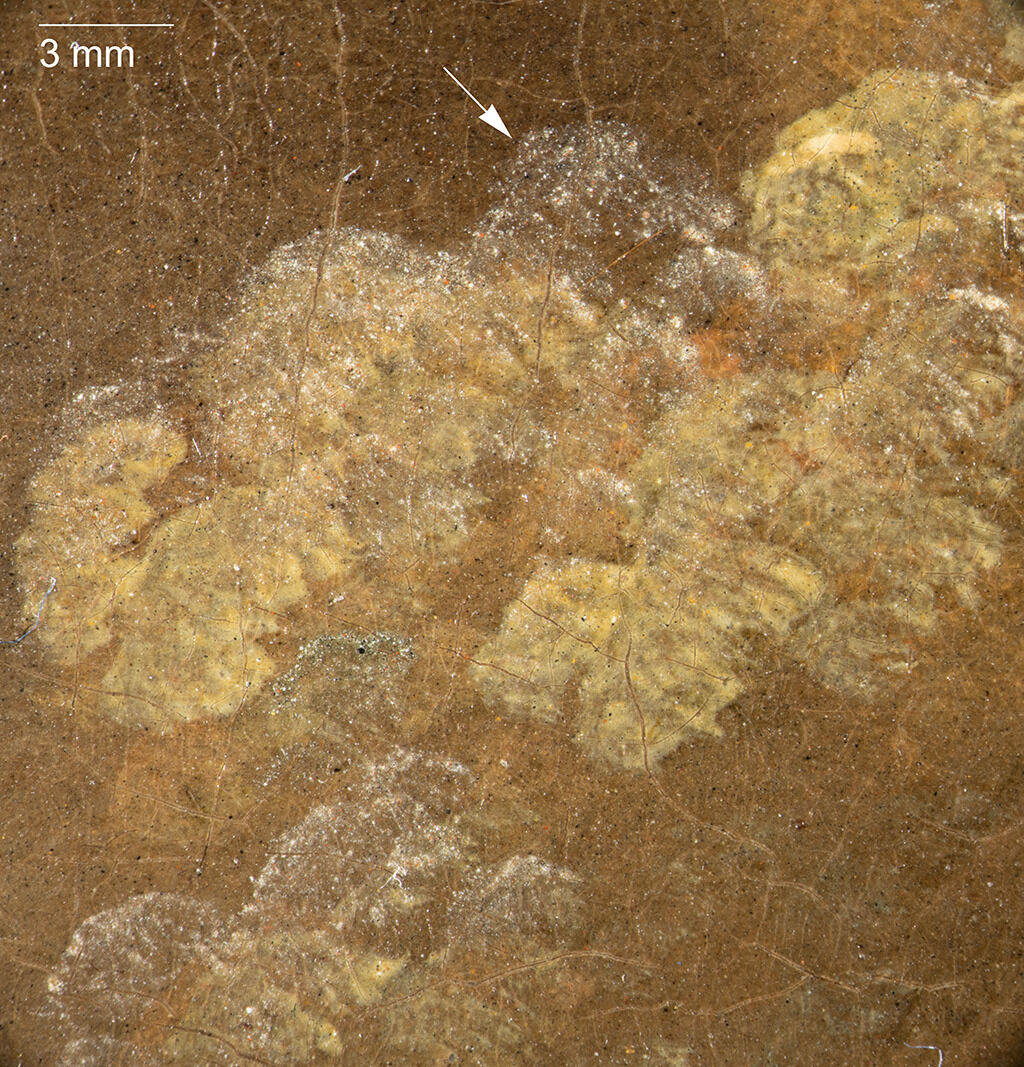

The canvas appears to have been prepared with a double groundground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. of pale earth red or peach, followed by an off-white layer.2A similar double ground was found on Fête Galante (ca. 1721–25; National Gallery, London), with an “orange-red followed by a warm buff colour.” Humphrey Wine, The Eighteenth Century French Paintings (London: National Gallery, 2018), 364. The lower peach layer is visible in few areas, such as along the original edges and in isolated cracks and small losses (Fig. 8). The luminosity of the upper ground layer remains visible throughout the composition. Across the majority of the composition, a thin semitransparent brown washwash: An application of thin paint that has been diluted with solvent. provides a warm tone beneath the foreground and trees.3This wash layer appears to be present in all areas except beneath the upper left sky. Within the sky, there do not appear to be any washes between the off-white ground and the final paint layer. Underlying, sweeping marks near the left edge of sky (Fig. 9) appear to be the result of the ground application with a broad spatula, although which ground layer cannot be determined.

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph in raking light of incised lines in the sky, The Garden Party (1725–30)

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph in raking light of incised lines in the sky, The Garden Party (1725–30)

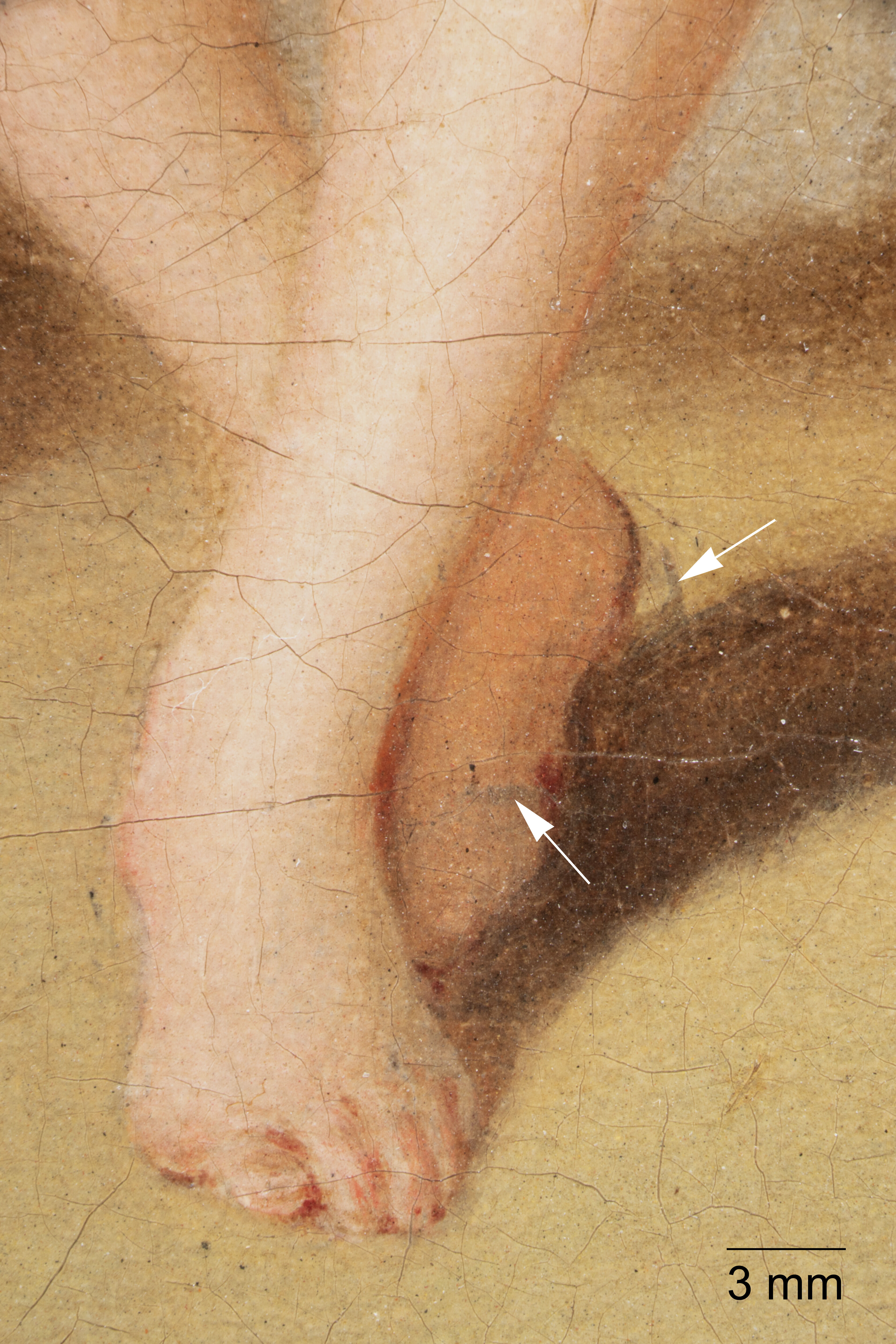

Fig. 10. Detail of the unfinished foot of the proper left attendant, exposing the painted underdrawing, The Garden Party (1725–30)

Fig. 10. Detail of the unfinished foot of the proper left attendant, exposing the painted underdrawing, The Garden Party (1725–30)

Infrared reflectographyinfrared reflectography (IRR): A form of infrared imaging that exploits the behavior of painting materials at wavelengths beyond those accessible to infrared photography. These advantages sometimes include a continuing increase in the transparency of pigments beyond wavelengths accessible to infrared photography (i.e, beyond 1,000 nanometers), rendering underdrawing more clearly. The resulting image is called an infrared reflectogram. Devices that came into common use in the 1980s such as the infrared vidicon effectively revealed these features but suffered from lack of sharpness and uneven response. Vidicons continue to be used out to 2,200 nanometers but several newer pixelated detectors including indium gallium arsenide and indium antimonide array detectors offer improvements. All of these devices are optimally used with filters constraining their response to those parts of the infrared spectrum that reveal the most within the constraints of the palette used for a given painting. They can be used for transmitted light imaging as well as in reflection. reveals a faint underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint., with a fluid medium used in the background and exterior figures, and a thin, dry medium used within the central figures. In the right-side foreground, the attendant’s proper left foot was left unpainted, revealing Pater’s sketching process (Fig. 10). Similarly, near the center of the composition, the initial sketch for the kneeling figure’s leg can be discerned beneath glazesglaze: A transparent, oil or resin-rich paint application that influences the tonality of the underlying paint. of brown paint applied to develop the folds and translucent shadows of the clothing (Fig. 11). The underdrawing is difficult to see in areas that are more thickly or opaquely painted, but glimpses can be found, such as in the hand of the central female figure and the fold of fabric where she pinches her gown (Fig. 12).

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of the central kneeling figure, illustrating the layering structure of the brown wash underpainting, The Garden Party (1725–30)

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of the central kneeling figure, illustrating the layering structure of the brown wash underpainting, The Garden Party (1725–30)

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of the underdrawing in the central female figure’s hand and gown, The Garden Party (1725–30)

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of the underdrawing in the central female figure’s hand and gown, The Garden Party (1725–30)

With the underdrawing in place, Pater laid in brown washes to roughly block in the scene. He then developed the figures with opaque layers. Brown washes remain visible in many of the faces, possibly an intentional technique used to create shadows. However, some of this may also be due to abrasionabrasion: A loss of surface material due to rubbing, scraping, frequent touching, or inexpert solvent cleaning. of the upper paint layer. Dashes of an opaque red earth pigment were used to create deeper shadows, such as for creases in the neck, while a translucent red lake pigmentlake pigment: An organic pigment manufactured by precipitating a soluble, natural colorant onto a colorless or white, insoluble, inorganic substrate. Historically, natural colorants were extracted from plants and insects. The substrate is traditionally hydrated aluminum oxide, but other substrates such as chalk (calcium carbonate), clay, or gypsum (calcium sulphate) have also been used. was used to enhance the facial features. The eye and lashes of the foreground girl were created with two flicks of red lake (Fig. 13).4No elemental analysis has been completed to identify the pigments. Similarly, opaque red paint was added to emphasize the contours of the figures, as is seen in the fingers of Figure 12. Each of these details in the uppermost paint layer appear to be final touches to the composition. The background was likely painted concurrently with the figures or after the figures. In much of the composition, the background paint was brought close to but does not touch the figures, while in a few locations, there is a slight overlap onto the figures as the background was refined.

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph of the foreground girl’s face, illustrating the use of translucent red lake and opaque red earth pigments, The Garden Party (1725–30)

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph of the foreground girl’s face, illustrating the use of translucent red lake and opaque red earth pigments, The Garden Party (1725–30)

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of the proper left male figure and the painterly ruffles of his shirt, The Garden Party (1725–30)

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of the proper left male figure and the painterly ruffles of his shirt, The Garden Party (1725–30)

A wide variety of brushwork is found throughout the composition. Many fabric textures were formed with painterly strokes, as, for example, in the white ruffles around the male figure’s neck (Fig. 14), while structured garments have a draftsman-like quality, such as in the boning in the bodice of the foreground girl (Fig. 15). Though most figures are fully rendered, in some instances Pater economically utilized the lower washes as both shadows and middle tones, while highlights were added to help define the shapes. An obvious example of this can be seen in the central woman’s shoe, where apart from the brown wash of the foreground, only a few lines of yellow form the structure and design (Fig. 16).

Fig. 15. Photomicrograph of the foreground girl’s bodice, The Garden Party (1725–30)

Fig. 15. Photomicrograph of the foreground girl’s bodice, The Garden Party (1725–30)

Fig. 16. Photomicrograph of the central female figure, illustrating the use of the brown underpainting and opaque yellow highlights to render her shoe, The Garden Party (1725–30)

Fig. 16. Photomicrograph of the central female figure, illustrating the use of the brown underpainting and opaque yellow highlights to render her shoe, The Garden Party (1725–30)

The majority of the painting was completed with wet-over-drywet-over-dry: An oil painting technique that involves layering paint over an already dried layer, resulting in no intermixing of paint or disruption to the lower paint strokes. or wet-over-wetwet-over-wet: An oil painting technique which involves drawing a stroke of one color across the wet paint of another color. paint application. The flowers in the female figures’ hair and in the foreground basket, however, appear to be more intentionally blended with wet-into-wetwet-into-wet: An oil painting technique which involves blending of colors on the picture surface. application, as Pater dragged colors together. This is especially noticeable when comparing the difference in paint applications between the loosely painted flowers and the structured basket in the foreground (Fig. 17). Here the artist pulled the highlights of the flowers over and through the lower saturated colors. In contrast, the weave of the basket does not appear to have intentional blending, as it was developed with pale yellow and muted orange lines, each under one millimeter wide.

Pater used atmospheric perspectiveatmospheric perspective: An artistic technique used to create the illusion of depth in a composition in which distant elements are cooler and more diffuse, causing them to recede. to create a hazy appearance for the distant foliage by means of pale colors and less defined forms. He gradually added greater detail and color saturation for elements approaching the foreground.5Similar descriptions of haziness or “foggy” backgrounds have been noted in other Pater paintings dated to the late 1720s. Christoph Martin Vogtherr, Watteau at the Wallace Collection (London: Wallace Collection, 2011), 133. Leaves of the trees range from greens to oranges, with red lake used sparingly to intensify the richness in the shadows. However, the overall color profile of the foliage may have shifted with age or damage. Many of the leaves in the final layer appear granular, with coarse white, black, and orange pigment particles, indicating that a sensitive pigment in the foliage is no longer present (Fig. 18). Whether the altered appearance was caused through abrasion or fading, it is difficult to speculate how the foliage appeared when it was freshly painted.

The painting is overall in good condition after having undergone multiple conservation campaigns throughout its history. Prior to entering the Nelson-Atkins collection, the painting was glue-paste lined, a structural treatment that continues to support the original canvas. In 1982, after entering the collection, a discolored varnish layer was removed and fillsfill material: A material added to a loss of paint and/or ground to create an area level with the surrounding original paint. at the turnover edgesturnover edge: The point at which the canvas begins to wrap around the stretcher, at the junction between the picture plane and tacking margin. See also foldover edge. were adjusted, and in some areas, the original canvas edges were revealed.6Forrest R. Bailey, October 22, 1982, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, no. F82-35/1. Despite widespread abrasion in the figures’ faces and in the background foliage, there is limited retouchingretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch. present, with most from the 1982 campaign along the turnover edges and in isolated losses within the picture plane.

Notes

-

The picture plane was increased between three and five millimeters on the top, bottom, and right edges during the lining process and approximately ten centimeters on the left edge near the top. Muted pink fill material and retouching covers the expanded space.

-

A similar double ground was found on Fête Galante (ca. 1721–25; National Gallery, London), with an “orange-red followed by a warm buff colour.” Humphrey Wine, The Eighteenth Century French Paintings (London: National Gallery, 2018), 364.

-

This wash layer appears to be present in all areas except beneath the upper left sky. Within the sky, there do not appear to be any washes between the off-white ground and the final paint layer.

-

No elemental analysis has been completed to identify the pigments.

-

Similar descriptions of haziness or “foggy” backgrounds have been noted in other Pater paintings dated to the late 1720s. Christoph Martin Vogtherr, Watteau at the Wallace Collection (London: Wallace Collection, 2011), 133.

-

Forrest R. Bailey, October 22, 1982, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, no. F82-35/1.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Garden Party (Fête Champêtre), 1725–30,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.326.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Garden Party (Fête Champêtre), 1725–30” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.326.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Garden Party (Fête Champêtre), 1725–30,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.326.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Garden Party (Fête Champêtre), 1725–30,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.326.4033.

Eugène Secrétan (1836–1899), Paris, by March–July 13, 1889 [1];

Purchased along with its pendant at his sale, Seventeen Ancient and Modern Pictures of the Highest Importance, Until Recently Forming Part of the Celebrated Secrétan Collection, Christie, Manson, and Woods, London, July 13, 1889, no. 3, as A Fete Champetre [sic], by Boussod, Valadon et Cie., Paris, stock no. 19985 or 19986, as Fête champêtre, July 15–December 3, 1889 [2];

Purchased from Boussod, Valadon, et Cie., by Lacroix, Paris, December 3, 1889 [3];

Marcel Bernstein (1840–1896), Paris, by June 8, 1892–1896;

Inherited by his wife Ida Bernstein (née Seligman, 1854–1921), or by descent to his son, Henry (1876–1953) Bernstein, Paris, 1896–1899;

Purchased from Ida Bernstein or Henry Bernstein by Ernest Gimpel, Paris, January 27, 1899–1901 [4];

Purchased from Gimpel by François “Ernest” Cronier (1840–1905), Paris, March 22, 1901–before August 27, 1905 [5];

Returned by Cronier to Ernest Gimpel and Wildenstein, as Rustic Pleasures, before August 27, 1905–March 1906 [6];

Purchased from Ernest Gimpel and Wildenstein by John Woodruff (1850–1920) and Kate (née Seney, 1868–1943) Simpson, New York, March 1906–May 16, 1920 [7];

Purchased from the estate of John Woodruff Simpson by Wildenstein and Co., New York, stock no. 1008d, 1921–September 14, 1982 [8];

Purchased from Wildenstein by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1982.

Notes

[1] Secrétan’s copper syndicate collapsed in March 1889. See email from Dr. Diana Kostyrko, Australian National University, to Meghan Gray, NAMA, April 6, 2017, NAMA curatorial files. Secrétan made his first acquisitions around 1876 but only began collecting old master paintings in 1880. Due to the generalized painting titles (like Fête champêtre) used in auction catalogues at the time, it is impossible to identify the museum’s painting prior to 1889. See email from Pamella Guerdat, PhD candidate at University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland, to Glynnis Stevenson, NAMA, August 11, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

[2] The paintings were both titled A Fete Champetre in the 1889 Secrétan sales catalogue. See “Goupil et Cie/Boussod, Valadon and Co. Stock Books, Series II. Galerie Boussod, Valadon Stock Books, 1875–1919, Livre no. 12, 1887–1891,” p. 115, stock no. 19985 or 19986, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. The pair was purchased together, and it is not clear from the stock books which painting was assigned which stock number. They were reserved for the July 13, 1889, London sale of the collection by Secrétan’s English creditors. See email from Kostyrko to Gray, April 6, 2017, NAMA curatorial files.

[3] Several possibilities for “Lacroix” are French painter Tristán Lacroix (1849–1914), active in Argentina from the end of the nineteenth century [See María Isabel Baldasarre, “Buenos Aires: An Art Metropolis in the Late Nineteenth Century,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 16, no. 1 (Spring 2017): https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2017.16.1.2]; Gaston Lacroix (1862–1909), an industrialist who lived at 104, avenue des Champs Elysées; or Gaston Lacroix, who earned his law degree in Toulouse in 1895. All three bought pictures from Boussod, Valadon, et Cie.

[4] Henry Bernstein’s biographers note that on January 27, 1899, either Henry or his mother Ida sold the Pater pendants to Gimpel. By this time, Henry and Ida were selling parts of the collection developed by Marcel Bernstein. Georges Bernstein Gruber and Gilbert Maurin, Bernstein, le magnifique: cinquante ans de théâtre, de passions et de vie parisienne (Paris: J. C. Lattès, 1988), 18.

[5] See René Gimpel, Diary of an Art Dealer (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1966), 305–06. Cronier returned the Pater pendants to Gimpel sometime before his suicide and estate sale in 1905. See email from Kostyrko to Gray, April 6, 2017, NAMA curatorial files.

[6] Gimpel went into business with Nathan and Ernest Wildenstein, and they opened their New York branch in 1902. See email from Kostyrko to Gray, April 6, 2017, NAMA curatorial files.

[7] See email from Joseph Baillio, Senior Vice President, Wildenstein and Company, to Meghan Gray, NAMA, November 9, 2016, NAMA curatorial files.

[8] See email from Baillio to Gray, November 9, 2016, NAMA curatorial files. In the Pater catalogue raisonné by Ingersoll-Smouse, the paintings are listed as in the collection Mrs. John Woodruff Simpson (née Katherine “Kate” Seney, 1868–1943), New York. See Florence Ingersoll-Smouse, Pater (Paris: Les beaux-arts, Édition d’études et de documents, 1928), no. 51, pp. 42, 120. Simpson often lent the paintings to exhibitions in New York, including in 1915 at the Benjamin Altman Gallery. Katherine Seney Simpson and her daughter, Jean Walker Simpson (1897–1980), inherited the bulk of the Woodruff estate and likely facilitated the sale of art to Wildenstein.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Garden Party (Fête Champêtre), 1725–30,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.326.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Garden Party (Fête Champêtre), 1725–30,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.326.4033.

Jean-Baptiste Pater, Gathering in a Park, 1719–20, oil on canvas, 25 9/16 x 31 7/8 in. (65 x 81 cm), Museu de Arte de São Paulo, Brazil, MASP.00052.

Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Dance and The Swing, ca. 1720s, oil on canvas, 30 1/4 x 39 3/8 in. (76.8 x 100 cm), sold at Collection Louis Grandchamp des Raux: Le choix de l’élégance En association avec Artcurial, Sotheby’s, Paris, March 26, 2015, lot 10.

Jean-Baptiste Pater, Rest in the Park, ca. 1728, oil on canvas, 21 7/8 x 25 1/4 in. (55.6 x 64.1 cm), Frick Pittsburgh Museums and Gardens, 1970.44.

Jean-Baptiste Pater, Fête Galante, ca. 1730, oil on canvas, 24 x 33 in. (61 x 83.8 cm), English Heritage, Kenwood House, London, IBK 954.

Jean-Baptiste Pater, Fête Galante, ca. 1730, oil on canvas, 24 x 33 in. (61 x 83.8 cm), English Heritage, Kenwood House, London, IBK 955.

Jean-Baptiste Pater, Fête in a Park, ca. 1730, oil on canvas, 20 3/4 x 25 3/8 in. (52.7 x 64.4 cm), Wallace Collection, London, P424.

Jean-Baptiste Pater, Fête Galante with Figures in a Park: “Amour et Badinage”, 1730s, oil on canvas, 27 1/2 x 35 1/2 in. (69.9 x 90.2 cm), sold at Important Old Master Paintings, Sotheby’s, New York, January 26, 2007, lot 98.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Garden Party (Fête Champêtre), 1725–30,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.326.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Garden Party (Fête Champêtre), 1725–30,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.326.4033.

Cents Chefs-d’œuvre des collections françaises et étrangères, Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, June 8–July 29, 1892, no. 31, as Le Goûter.

Loan Exhibition of Fifty-nine Masterpieces of Ancient and Modern Schools, Benjamin Altman Gallery, New York, March 24–April 4, 1915, no. 38, as Le Gouter [sic].

Exposition Rococo: poésie et rêve de la peinture française au XVIIIe siècle, Otani Museum, Nishinomiya, Japan, January 14–February 12, 1978, no. 4, as Fête champêtre.

A Bountiful Decade: Selected Acquisitions 1977–1987, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1987, no. 51, as Le Goûter.

Intimate Encounters: Love and Domesticity in Eighteenth-Century France, Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, October 4, 1997–January 4, 1998; The Toledo Museum of Art, OH, February 15–May 10, 1998; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, May 31–August 23, 1998, no. 7, as The Picnic.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Garden Party (Fête Champêtre), 1725–30,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.326.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Garden Party (Fête Champêtre), 1725–30,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.326.4033.

Possibly Tableaux anciens et modernes. . . .: catalogue de la collection de feu M. le duc de B[ojano] (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, January 19–20, 1882), 24, as Les plaisirs champêtres or Conversation galante.

F. G., “Galerie Sécretan,” Le Gaulois, no. 2500 (July 3, 1889): 2, as Fête champêtre or seconde Fête champêtre.

“The Secretan [sic] Sale,” Times (London), no. 32,741 (July 3, 1889): 7.

“Seventeen Secrétan Pictures,” Times (London), no. 32,746 (July 9, 1889): 11.

Catalogue of Ancient and Modern Pictures of the Highest Importance, Until Recently Forming Part of the Celebrated Secrétan Collection; in conjunction with Messrs. Boussod, Valadon, et Cie., London and Paris, and M. C. Sedelmeyer, Paris (London: Christie, Manson, and Woods, July 13, 1889), B2, as A Fete Champetre [sic].

Frederick Wedmore, “The London Group of Secretan [sic] Pictures,” Academy 36, no. 897 (July 13, 1889): 27, as Fête Champêtre.

F. G., “La Vente Secrétan a [sic] Londres,” Le Gaulois, no. 2503 (July 14, 1889): 2, as Fête champêtre, treize personnages dans un jardin près d’une fontaine sculptée.

L. K., “At the Secretan [sic] Sale: Scenes and Incidents of the Great Occasion. Eminent Persons Who Filled the Room—Intensity of the Interest Shown—Millet and Meissonier,” New York Times 38, no. 11,817 (July 14, 1889): 5.

“Fine Pictures and Big Prices: The Secretan [sic] Pictures,” British Architect 32 (July 19, 1889): 52, as Fêtes Champêtre.

“Sales,” Athenaeum, no. 3221 (July 20, 1889): 104, as Fête Champêtre.

Montezuma, “My Note Book,” Art Amateur 21, no. 4 (September 1889): 66, as Fête Champêtre.

George Lafenestre and L[éon] Roger-Milès, Cents Chefs-d’Œuvre des Collections Françaises et Étrangères, exh. cat. (Paris: Georges Petit, 1892), 19, 63–64, 152, (repro.), as le Goûter.

Exposition de Peinture: Cent Chefs-d’œuvre des Écoles Françaises et Étrangères (Deuxième Exposition), exh. cat. (Paris: Georges Petit, 1892), 35, as Le Goûter.

W. Roberts, Memorials of Christie’s: A Record of Art Sales from 1766 to 1896 (London: G. Bell and Sons, 1897), 2:140.

Georges Lafenestre, Artistes et Amateurs (Paris: Société d’Édition Artistique, 1900), 315, as le Goûter.

Loan Exhibition of Fifty-nine Masterpieces of Ancient and Modern Schools, exh. cat. (New York: Benjamin Altman Gallery, 1915), unpaginated, as Le Gouter [sic].

“Year’s Best Show of Art for War Aid: Owners of More Than 50 Masterpieces Join Exhibition at Altman Gallery,” New York Times 64, no. 20,878 (March 24, 1915): 11.

“A Magnificent Loan Exhibition: Masterpieces of Eighteenth Century French Art on View at the Residence of the Late Benjamin Altman,” New York Times 64, no. 20,882 (March 28, 1915): SM22.

Guy Pène du Bois, “Mistresses of Famous American Collectors: The Collection of Mrs. John W. Simpson,” Arts and Decoration (March 1917): 234.

Florence Ingersoll-Smouse, Pater (Paris: Les beaux-arts, Édition d’études et de documents, 1928), no. 51, pp. 42, 120, (repro.), as Fête Champêtre ou Le Gouter [sic].

René Gimpel, Diary of an Art Dealer, trans. John Rosenberg (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1966), 301, 305–06, as Rustic Pleasures.

Didier Romand, “La Cote des peintres: peintures,” Gazette de l’Hôtel Drouot, no. 42 (December 8, 1972): 19, as Fête champêtre ou Le goûter.

Exposition Rococo: poésie et rêve de la peinture française au XVIIIe siècle, exh. cat. (Nishinomiya, Japan: Otani Museum, 1978), unpaginated, as Fête champêtre.

“New Acquisitions,” Gallery Events (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (November 1982): unpaginated, as Fête Champêtre.

Donald Hoffmann, “Pater oils grace museum collection,” Kansas City Star 103, no. 43 (November 7, 1982): 9-I, (repro.), as Fete [sic] Champetre [sic].

Bill Marvel, “How good is the Nelson?” STAR Magazine, supplement, Kansas City Star 103, no. 186 (April 24, 1983): S26.

John Russell, “Art View: A Panoramic View of A French Master of Still Lifes,” New York Times 132, no. 45,756 (July 31, 1983): H25.

Donald Hoffmann, “Art journal: More about Oudry,” Kansas City Star 103, no. 292 (August 28, 1983): 8E.

Roger Ward, ed., A Bountiful Decade: Selected Acquisitions, 1977–1987, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1987), 122–23, (repro.), as Le Goûter.

Georges Bernstein Gruber and Gilbert Maurin, Bernstein, le magnifique: cinquante ans de théâtre, de passions et de vie parisienne (Paris: J. C. Lattès, 1988), 18.

Gloria Groom, Edouard Vuillard, Painter-decorator: Patrons and Projects, 1892–1912 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1993), 238n18.

Alice Thorson, “Traveling treasures: Some gallery favorites to go on tour as Nelson gears up for expansion,” Kansas City Star 118, no. 87 (December 13, 1997): E2.

Richard Rand, Intimate Encounters: Love and Domesticity in Eighteenth-Century France, exh. cat. (Hanover, NH: Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, 1997), 41, 101–03, (repro.), as Le Goûter and The Picnic.

Colin B. Bailey, Philip Conisbee, and Thomas W. Gaehtgens, The Age of Watteau, Chardin, and Fragonard: Masterpieces of French Genre Painting, exh. cat. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003), 52–53, (repro.), as The Picnic.

Tableaux Anciens et du XIXe siècle: Incluant 50 œuvres vendues sans prix de réserve (Paris: Christie’s, June 24, 2004), 103, as Le Goûter.

Emmanuel Bénézit, Dictionnaire critique et documentaire des peintres, sculpteurs, dessinateurs, et graveurs de tous les temps et de tous les pays (Paris: Gründ, 2006), 10:988, as Fêtes champêtres.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 89, (repro.), as Le Goûter.

Diana Kostyrko, The Journal of a Transatlantic Art Dealer: René Gimpel 1918–1939 (London: Harvey Miller, 2017), 153–54, as Le Goûter.

Christel H. Force, ed., Pioneers of the Global Art Market: Paris-Based Dealer Networks, 1850–1950 (London: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020), 241n6, as Les Plaisirs champêtre.

Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Bathers, 1728–30

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Diana M. Jaskierny, “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Bathers, 1728–30,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.327.2088.

MLA:

Jaskierny, Diana M. “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Bathers, 1728–30,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.327.2088.

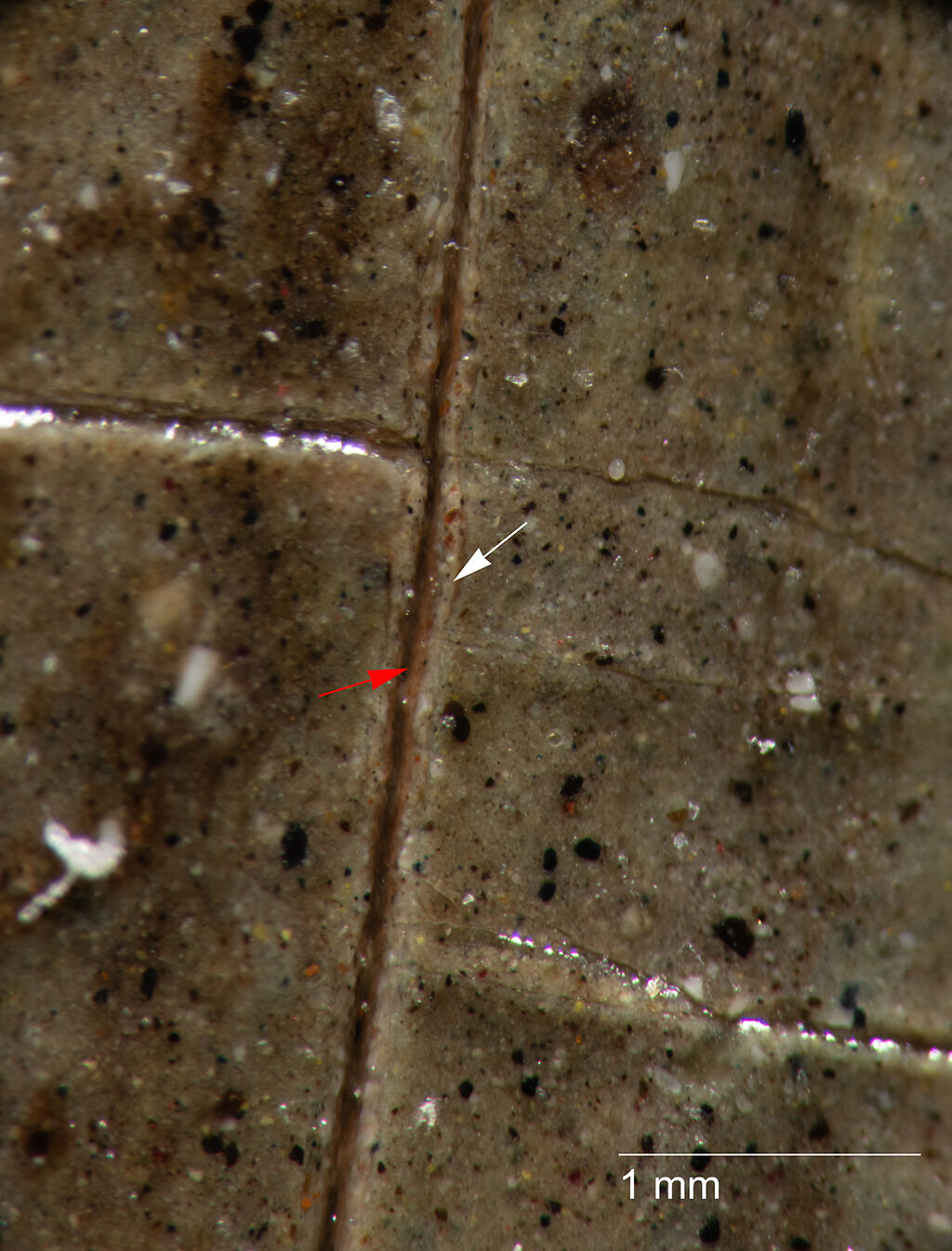

The Bathers, by Jean-Baptiste Pater, reveals much of the artist’s planning process through an elaborate underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint. that he modified as he worked through washwash: An application of thin paint that has been diluted with solvent.-like layers and lively brushwork. The painting was executed on a plain-weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas and is attached to a five-member stretcherstretcher: A wooden structure to which the painting’s canvas is attached. Unlike strainers, stretchers can be expanded slightly at the joints to improve canvas tension and avoid sagging due to humidity changes or aging.. Though the tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. were removed, likely during an early lininglining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive. process, pronounced cuspingcusping: A scalloped pattern along the canvas edges that relates to how the canvas was stretched. Primary cusping reveals where tacks secured the canvas to the support while the ground layer was applied. Secondary cusping can form when a pre-primed canvas is re-stretched by the artist prior to painting. is visible throughout the perimeter of the picture planepicture plane: The two-dimensional surface where the artist applies paint., indicating that the painting was not significantly altered in format or dimensions.1Former conservator Forrest Bailey speculated that portions of the original tacking margins may now extend onto the picture plane due to the slight increase in size; however, this is difficult to confirm due to the extensive fill material and retouching around the edges. In the radiograph, there are no clear tack holes visible to indicate that the tacking margins are present. Forrest R. Bailey, August 25, 1982, examination report, NAMA conservation file, no. F82-35/2.

It is not entirely clear how the ground layerground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. was applied or what the layer structure is. In many areas where the ground is visible, throughout much of the sky and some of the foreground, it appears to be a pale red-earth tone (Fig. 19). However, in the architecture and in many figures, there appears to be an off-white layer on top of the red-earth ground. It is possible that Pater applied a red-earth ground across the entirety of the canvas, while the off-white layer was used to block in the active parts of the composition.

Fig. 19. Photomicrograph of the red-earth ground layer visible through abrasion in the sky, The Bathers (1728–30)

Fig. 19. Photomicrograph of the red-earth ground layer visible through abrasion in the sky, The Bathers (1728–30)

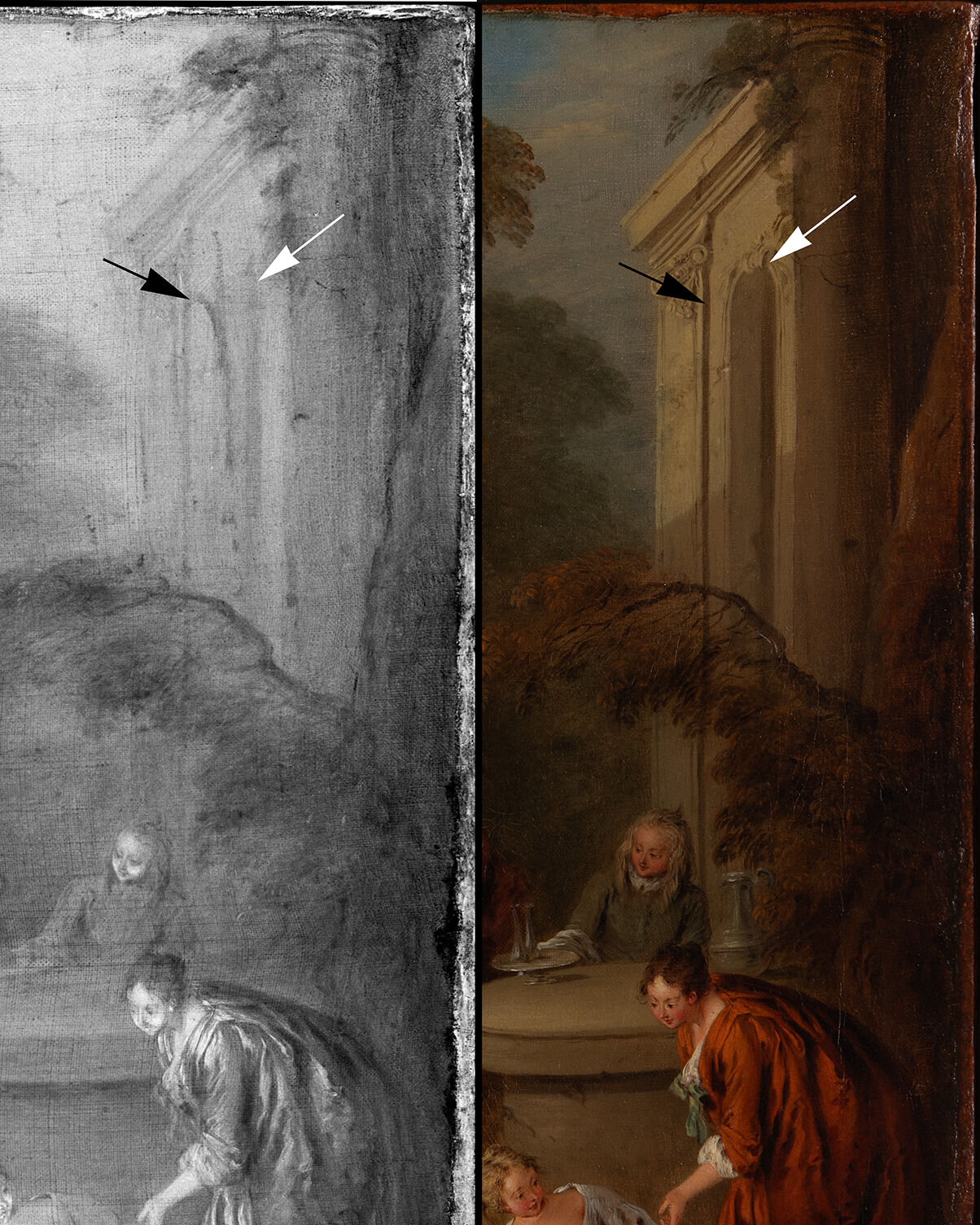

Fig. 20. Infrared reflectograph captured at 1950 nanometers, with a white arrow indicating the fluid medium and a black arrow indicating the dry medium, The Bathers (1728–30)

Fig. 20. Infrared reflectograph captured at 1950 nanometers, with a white arrow indicating the fluid medium and a black arrow indicating the dry medium, The Bathers (1728–30)

Infrared reflectographyinfrared reflectography (IRR): A form of infrared imaging that exploits the behavior of painting materials at wavelengths beyond those accessible to infrared photography. These advantages sometimes include a continuing increase in the transparency of pigments beyond wavelengths accessible to infrared photography (i.e, beyond 1,000 nanometers), rendering underdrawing more clearly. The resulting image is called an infrared reflectogram. Devices that came into common use in the 1980s such as the infrared vidicon effectively revealed these features but suffered from lack of sharpness and uneven response. Vidicons continue to be used out to 2,200 nanometers but several newer pixelated detectors including indium gallium arsenide and indium antimonide array detectors offer improvements. All of these devices are optimally used with filters constraining their response to those parts of the infrared spectrum that reveal the most within the constraints of the palette used for a given painting. They can be used for transmitted light imaging as well as in reflection. reveals that two methods were used when developing the underlying drawing. Within the background, both the trees and the tall arch were sketched using a fluid medium, likely applied by brush based on the variation of line thickness. In contrast, the drawing of the figures and much of the foreground was formed with fine lines of a dry medium such as charcoal (Fig. 20). Throughout the painting, due to the thin application of paint, some of these fine lines remain visible in standard light, such as around the central figure’s feet (Fig. 21).

Fig. 21. Photomicrograph of the underdrawing visible in standard light of the original foot placement for the female figure in the yellow skirt, The Bathers (1728–30)

Fig. 21. Photomicrograph of the underdrawing visible in standard light of the original foot placement for the female figure in the yellow skirt, The Bathers (1728–30)

Fig. 22. Detail of arch in the infrared reflectogram, captured at 1950 nanometers (left) and in standard light (right), illustrating the changed position, with the black arrows indicating the original drawn placement and the white arrows indicating the final painted placement, The Bathers (1728–30)

Fig. 22. Detail of arch in the infrared reflectogram, captured at 1950 nanometers (left) and in standard light (right), illustrating the changed position, with the black arrows indicating the original drawn placement and the white arrows indicating the final painted placement, The Bathers (1728–30)

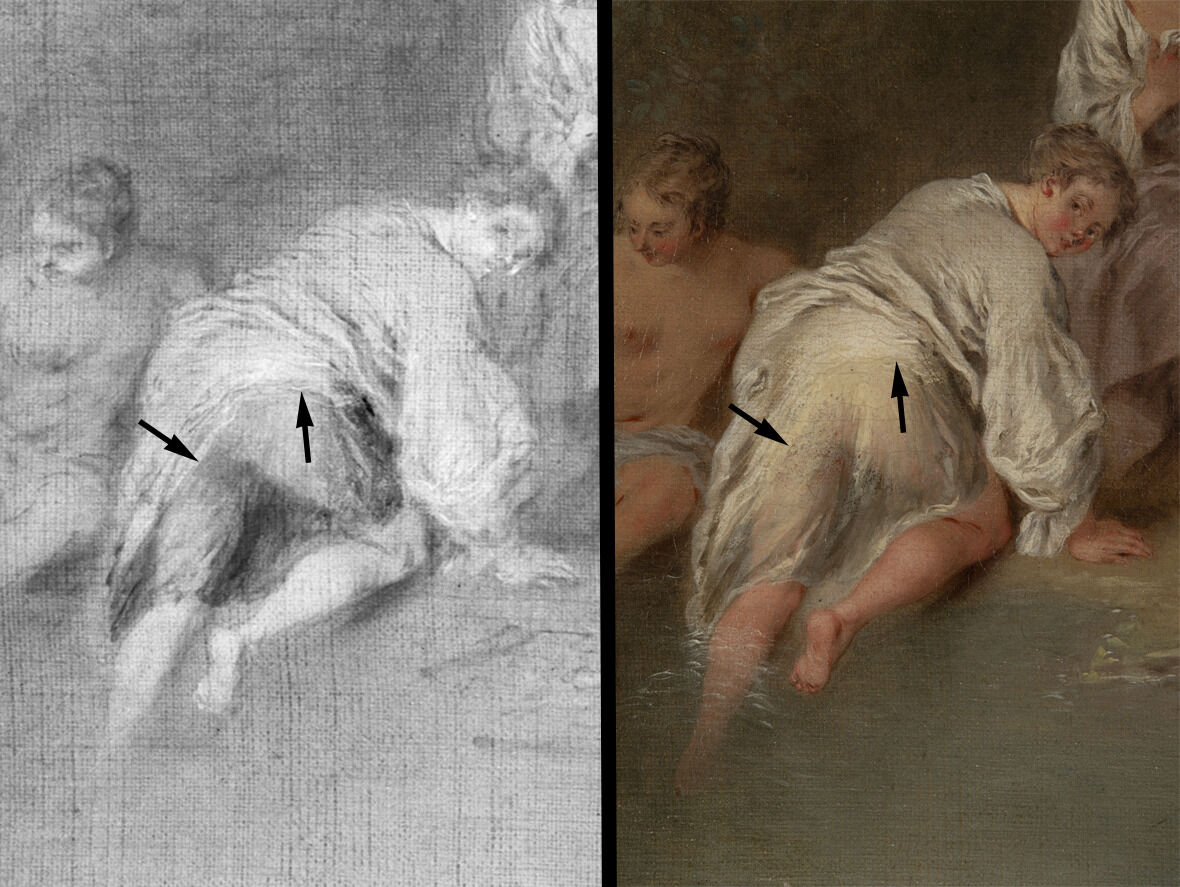

The underdrawing reveals that multiple changes were made by the artist using both types of media. The fluid underdrawing of the background confirms that the original location of the arch’s opening was shifted slightly to the left of where Pater ultimately painted it (Fig. 22). Within the figures, more adjustments were made, specifically with the orientation of some heads. The central figure who rises the tallest among the cluster of figures was shifted, as indicated by the oval that once marked the position of her head, with a horizontal line designating the brow placement. Additionally, the second figure from the left edge was also adjusted, with her head turning toward the water as opposed to the lower left corner (Fig. 23). It is possible that Pater made this latter modification to avoid repetitive poses in relation to the right-most figure and the seated central figure, each with their heads positioned in a similar manner.

Fig. 23. Details of figures in the infrared reflectogram, captured at 1950 nanometers (left) and in standard light (right), illustrating the changed positions of heads, with arrows indicating the original drawn placements, The Bathers (1728–30)

Fig. 23. Details of figures in the infrared reflectogram, captured at 1950 nanometers (left) and in standard light (right), illustrating the changed positions of heads, with arrows indicating the original drawn placements, The Bathers (1728–30)

Fig. 24. Details of the girl in The Garden Party (left; 1725–30) and the woman in The Bathers (right; 1728–30), illustrating the similarities in figures

Fig. 24. Details of the girl in The Garden Party (left; 1725–30) and the woman in The Bathers (right; 1728–30), illustrating the similarities in figures

Fig. 25. Jean-Baptiste Pater, Bathing Party in a Park, ca. 1730, oil on canvas, 25 1/4 x 33 7/16 in. (64.2 x 85 cm), The Wallace Collection, London, P426. Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. The dotted lines surround a group of figures which is simliar to that in The Bathers in the Nelson-Atkins collection.

Fig. 25. Jean-Baptiste Pater, Bathing Party in a Park, ca. 1730, oil on canvas, 25 1/4 x 33 7/16 in. (64.2 x 85 cm), The Wallace Collection, London, P426. Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0. The dotted lines surround a group of figures which is simliar to that in The Bathers in the Nelson-Atkins collection.

While these changes demonstrate that Pater continued to work out his composition into the painting stage, the artist was also known for his formulaic approach to figures and architecture. Frequently reusing figures between paintings, his work has been described as “a theme with few variations.”2David Wakefield, French Eighteenth-Century Painting (New York: Alpine Fine Arts Collection, 1984), 36. An example of this can be found in the Nelson-Atkins paintings. In The Bathers, the head of the figure closest to the foreground is also present in The Garden Party (1725–30), though in the latter, she is portrayed as a young girl, while in the former she appears to be an adult (Fig. 24). In the painting Bathing Party in a Park (Fig. 25), a similar group of figures in the lower right corner mimics the group found in the lower right corner of the Nelson-Atkins version, The Bathers. In this instance, however, the figure previously in question has light hair and a slightly different face (Fig. 26).

Fig. 26. Comparison of the foreground woman in Bathing Party in a Park (left; The Wallace Collection, London; ca. 1730) and of the foreground woman in The Bathers (right; the Nelson-Atkins; 1728–30)

Fig. 26. Comparison of the foreground woman in Bathing Party in a Park (left; The Wallace Collection, London; ca. 1730) and of the foreground woman in The Bathers (right; the Nelson-Atkins; 1728–30)

Fig. 27. Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Bathing Party, early 18th century, oil on canvas, 26 1/ 4 x 32 1/4 in. (66.8 x 81.9 cm), Toledo Museum of Art, 1954.28

Fig. 27. Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Bathing Party, early 18th century, oil on canvas, 26 1/ 4 x 32 1/4 in. (66.8 x 81.9 cm), Toledo Museum of Art, 1954.28

Fig. 28. Comparison of the central figure in The Bathing Party (left; Toledo Museum of Art, T1954.28) and the central figure in The Bathers (right; the Nelson-Atkins; 1728–30)

Fig. 28. Comparison of the central figure in The Bathing Party (left; Toledo Museum of Art, T1954.28) and the central figure in The Bathers (right; the Nelson-Atkins; 1728–30)

One change to the Nelson-Atkins composition that was not made by the

artist involves the central, kneeling woman in white, who turns

backwards to look toward the viewer. As with other figures, she has also

been repeated in other paintings and can be found in The Bathing Party

(Fig. 27). However, a notable difference exists in the depiction of the

lower portion of clothing, with the version in the Toledo Museum of Art

being slightly more revealing in its length (Fig. 28).3Another similar variation of this figure more closely resembling that of the Toledo Museum of Art can be found in the collection of the Birmingham Museum of Art: Les Baigneuses (Female Bathers in a Landscape), ca. 1735, https://www.artsbma.org

Fig. 29. Detail of central kneeling figure in the infrared reflectogram, captured at 1950 nanometers (left) and in standard light (right), revealing overpaint, with the black arrows indicating where the original paint likely ended, The Bathers (1728–30)

Fig. 29. Detail of central kneeling figure in the infrared reflectogram, captured at 1950 nanometers (left) and in standard light (right), revealing overpaint, with the black arrows indicating where the original paint likely ended, The Bathers (1728–30)

Fig. 30. Photomicrograph of the foreground woman’s red skirt, showing the thin red wash, deeper red shadows, and opaque red highlights, The Bathers (1728–30)

Fig. 30. Photomicrograph of the foreground woman’s red skirt, showing the thin red wash, deeper red shadows, and opaque red highlights, The Bathers (1728–30)

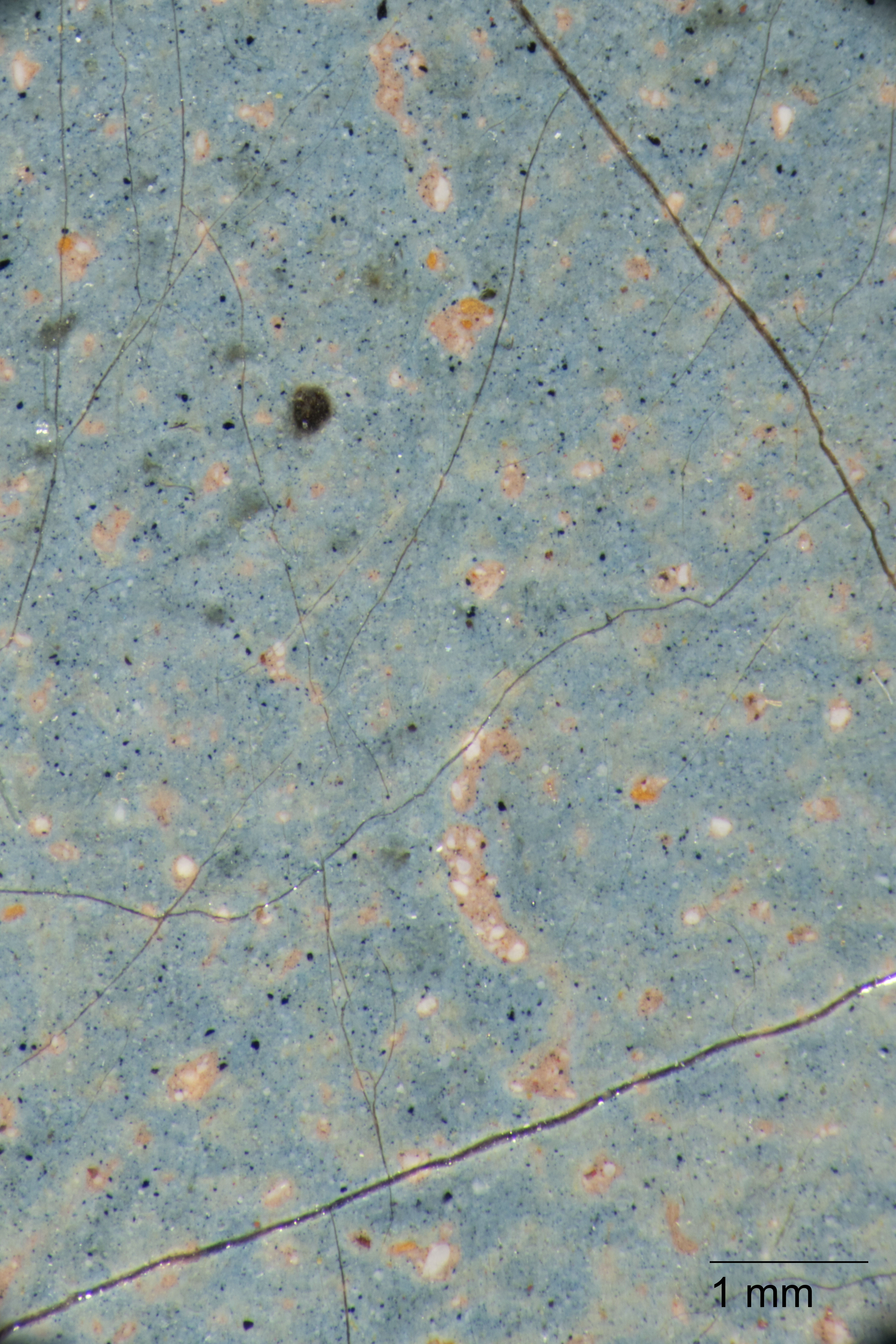

With active, loose brushwork and overall thin passages, the application of paint in The Bathers often resembles that of a painted sketch6Pater’s works are sometimes described as being “executed in the manner of a sketch,” partially because of the speed in which he was creating the repetitious imagery, as found in The Bathers. Patrick Ramade and Martin Eidelberg, Watteau et la fête galante, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2004), 186. in comparison to the brushwork found on The Garden Party. The fabric, specifically that of the women’s skirts, was first blocked in with a thin wash, as is found in the figure nearest to the viewer. Here, the thin red wash remains clearly visible, and the texture of the canvas weave is prominent beneath it. Pater then added some deeper reds for shadows before adding an opaque red admixture to create folds and volume in the fabric (Fig. 30). To create the rich blue fabric for the skirt on the figure just right of center, a gray-brown wash was applied first, and then the folds were developed with black shadows and green-blue highlights (Fig. 31).

Fig. 31. Photomicrograph of the center-right woman’s blue skirt, showing the thin gray-brown wash, deeper black shadows, and green-blue highlights, The Bathers (1728–30)

Fig. 31. Photomicrograph of the center-right woman’s blue skirt, showing the thin gray-brown wash, deeper black shadows, and green-blue highlights, The Bathers (1728–30)

Fig. 32. Photomicrograph of the face of the central kneeling woman, illustrating the fine brushwork, The Bathers (1728–30)

Fig. 32. Photomicrograph of the face of the central kneeling woman, illustrating the fine brushwork, The Bathers (1728–30)

In contrast to the animated brushwork of the clothing, the figures’ heads were delicately painted with small brushes, sometimes producing lines as thin as one tenth of a millimeter. The features of the faces were formed with fine lines of brown and red paint, as is seen in the central kneeling figure (Fig. 32). Here the hair was constructed with short, thin brushstrokes, alternating highlights and shadows while allowing a lower brown wash to remain visible. Through the thinly painted hair, glimpses of underdrawing peek around the temple and ear, adding to the depth of the form.

The painting is in fair condition and has undergone multiple conservation campaigns. Likely early in its history, the painting was glue-paste lined, which appears to have extended the overall picture plane size by a few millimeters on each side. Though much of the translucency of the bathing scene is a result of the artist’s technique, abrasionabrasion: A loss of surface material due to rubbing, scraping, frequent touching, or inexpert solvent cleaning. is widespread across the painting. A few areas with small losses have been retouchedretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch., with the majority of the restoration occurring along the edges and within the architecture in the proper left background.7Forrest R. Bailey, October 20, 1982, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, no. F82-35/2.

Notes

-

Former conservator Forrest Bailey speculated that portions of the original tacking margins may now extend onto the picture plane due to the slight increase in size; however, this is difficult to confirm due to the extensive fill material and retouching around the edges. In the radiograph, there are no clear tack holes visible to indicate that the tacking margins are present. Forrest R. Bailey, August 25, 1982, examination report, NAMA conservation file, no. F82-35/2.

-

David Wakefield, French Eighteenth-Century Painting (New York: Alpine Fine Arts Collection, 1984), 36.

-

Another similar variation of this figure more closely resembling that of the Toledo Museum of Art can be found in the collection of the Birmingham Museum of Art: Les Baigneuses (Female Bathers in a Landscape), ca. 1735, https://www.artsbma.org

/collection ./les-baigneuses-female-bathers-in-a-landscape/ -

Though the garment appears to be somewhat transparent, when comparing the painting today to the image reproduced in the 1928 catalogue raisonné, it appears this restoration has increased in transparency with age. Likely, it appeared more opaque and cohesive with the figure when it was first added. Florence Ingersoll-Smouse, Jean-Baptiste Joseph Pater: Biographie et catalogue critiques, l’œuvre complète de l’artiste (Paris: Les Beaux-arts, 1928), 121.

-

Pierre Schneider, The World of Watteau: 1684–1721 (New York: Time Incorporated, 1967), 76, 79–80.

-

Pater’s works are sometimes described as being “executed in the manner of a sketch,” partially because of the speed in which he was creating the repetitious imagery, as found in The Bathers. Patrick Ramade and Martin Eidelberg, Watteau et la fête galante, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2004), 186.

-

Forrest R. Bailey, October 20, 1982, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, no. F82-35/2.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Bathers, 1728–30,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.327.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Bathers, 1728–30,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.327.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Bathers, 1728–30,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.327.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Bathers, 1728–30,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.327.4033.

Eugène Secrétan (1836–1899), Paris, by March 1889–July 13, 1889 [1];

Purchased along with its pendant at his sale, Seventeen Ancient and Modern Pictures of the Highest Importance, Until Recently Forming Part of the Celebrated Secrétan Collection, Christie, Manson, and Woods, London, July 13, 1889, no. 4, erroneously as A Fete Champetre [sic], by Boussod, Valadon, et Cie., Paris, stock no. 19985 or 19986, as Fête champêtre, July 15–December 3, 1889 [2];

Purchased from Boussod, Valadon, et Cie., by Lacroix, Paris, December 3, 1889 [3];

Marcel Bernstein (1840–1896), Paris, by June 8, 1892–1896;

Inherited by his wife Ida Bernstein (née Seligman, 1854–1921), or by descent to his son, Henry Bernstein (1876–1953), Paris, 1896–1899;

Purchased from Ida Bernstein or Henry Bernstein by Ernest Gimpel, Paris, January 27, 1899–1901 [4];

Purchased from Gimpel by François “Ernest” Cronier (ca. 1840–1905), Paris, March 22, 1901–before August 27, 1905 [5];

Returned by Cronier to Ernest Gimpel and Wildenstein, as The Bath, before August 27, 1905–March 1906 [6];

Purchased from Ernest Gimpel and Wildenstein by John Woodruff (1850–1920) and Kate (née Seney, 1868–1943) Simpson, New York, March 1906–May 16, 1920 [7];

Purchased from the estate of John Woodruff Simpson by Wildenstein and Co., New York, stock no. 1007, 1921–September 14, 1982 [8];

Purchased from Wildenstein by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1982.

Notes

[1] Secrétan’s copper syndicate collapsed in March 1889. See email from Dr. Diana Kostyrko, Australian National University, to Meghan Gray, NAMA, April 6, 2017, NAMA curatorial files. Secrétan made his first acquisitions around 1876 but only began collecting old master paintings in 1880. Due to the generalized painting titles (like Fête champêtre) used in auction catalogues at the time, it is impossible to identify the museum’s painting prior to 1889. See email from Pamella Guerdat, PhD candidate at University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland, to Glynnis Stevenson, NAMA, August 11, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

[2] The paintings were both titled A Fete Champetre in the 1889 Secrétan sales catalogue. See “Goupil et Cie/Boussod, Valadon, and Co. Stock Books, Series II. Galerie Boussod, Valadon Stock Books, 1875–1919, Livre no. 12, 1887–1891,” p. 115, stock no. 19985 or 19986, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. The pair was purchased together, and it is not clear from the stock books which painting was assigned which stock number. They were reserved for the July 13, 1889, London sale of the collection by Secrétan’s English creditors. See email from Kostyrko to Gray, April 6, 2017, NAMA curatorial files.