![]()

Armand Guillaumin, Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine, ca. 1874

| Artist | Armand Guillaumin, French, 1841–1927 |

| Title | Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine |

| Object Date | ca. 1874 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Paysage d’Île de France |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 19 3/8 x 25 3/4 in. (49.2 x 65.4 cm) |

| Signature | Signed lower left: Guillaumin |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Promised gift of Robert L. and Barbara Bloch in honor of his parents, Henry and Marion Bloch, and the 75th anniversary of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 27-1989 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Armand Guillaumin, Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine, ca. 1874,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.621.5407.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Armand Guillaumin, Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine, ca. 1874,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.621.5407.

During his lifetime, Armand Guillaumin (1841–1927) was considered one of the premiere French Impressionist landscape artists. From relatively humble beginnings, over the course of an increasingly successful career, he rose to a position of prominence among his contemporaries and achieved considerable commercial success within Parisian art circles and abroad.1Guillaumin was featured in three solo exhibitions by gallerist Paul Durand-Ruel in the years 1894, 1896, and 1898. See Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Paul Durand-Ruel: Memoirs of the First Impressionist Art Dealer, 1831–1922 (Paris: Flammarion, 2014), 213, 216–18. Together with Paul Cezanne (1839–1906) and others, Guillaumin helped redefine French landscape painting. In his approach to landscape and appreciation for industry, he ushered in a modern pictorial process for those subjects. Indeed, in 1886, the critic Félix Fénéon referred to Guillaumin as “the beautiful painter of landscapes.”2Félix Fénéon, “Les Impressionnistes en 1886,” La Vogue (1886): 395. “Et ce coloriste furieux, ce beau peintre de paysages gorgés de sèves et haletants, a restitué à toutes ses figures humaines une robuste et placide animalité” (“And this furious colorist, this beautiful painter of breathless and sap-drenched landscapes, has restored to all his human figures a robust and placid animality”). Translation by the author. Today many of his works are represented in the collections of major museums and have been included in exhibitions of recent decades dedicated to Impressionism.3See, for example, Denis Coutagne, Cézanne and Paris, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la RMN-Grand Palais, 2011); Felix Kramer, Monet and the Birth of Impressionism, exh. cat. (Munich: Prestel, 2015); and Alexander Babin and Albert Grigorevich Kostenevich, Impressionism: Sensation and Inspiration: Highlights from the Hermitage, exh. cat. (Amsterdam: Museumshop Hermitage Amsterdam, 2012).

Despite these contributions, Guillaumin is arguably the French Impressionist landscape innovator most neglected by today’s scholars. Many of his works remain largely unknown, among them the Nelson-Atkins landscape, which was previously dated 1876–1877 and titled Landscape, Île-de-France.4The Nelson-Atkins landscape entered the collection of Robert Bloch in June 1989, but it was not exhibited in public until 2007, when it was included in an exhibition at the Nelson Atkins Museum of Art. See Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 14, 74–78, 158. The Nelson-Atkins landscape is also not reproduced in the artist’s catalogue raisonné: G. Serret and D. Fabiani, Armand Guillaumin 1841–1927 (Paris: Mayer, 1971). New research reveals that Guillaumin probably completed the painting earlier and that it depicts Ivry-sur-Seine, an industrial town located along the Paris-Orléans railway, where the artist was employed.5Christopher Gray, “1841–1869: Beginnings,” in Armand Guillaumin (Chester, CT: Pequot Press, 1972), 2. See also Marco-Edo Tralbaut, Armand Guillaumin (1841–1927): En famille et sur le motif (Antwerp: Peré, 1971). Likely painted around 1874, it may well rank among Guillaumin’s earliest and most ambitious compositions produced in and around the southeastern suburb of Ivry-sur-Seine in the early 1870s.

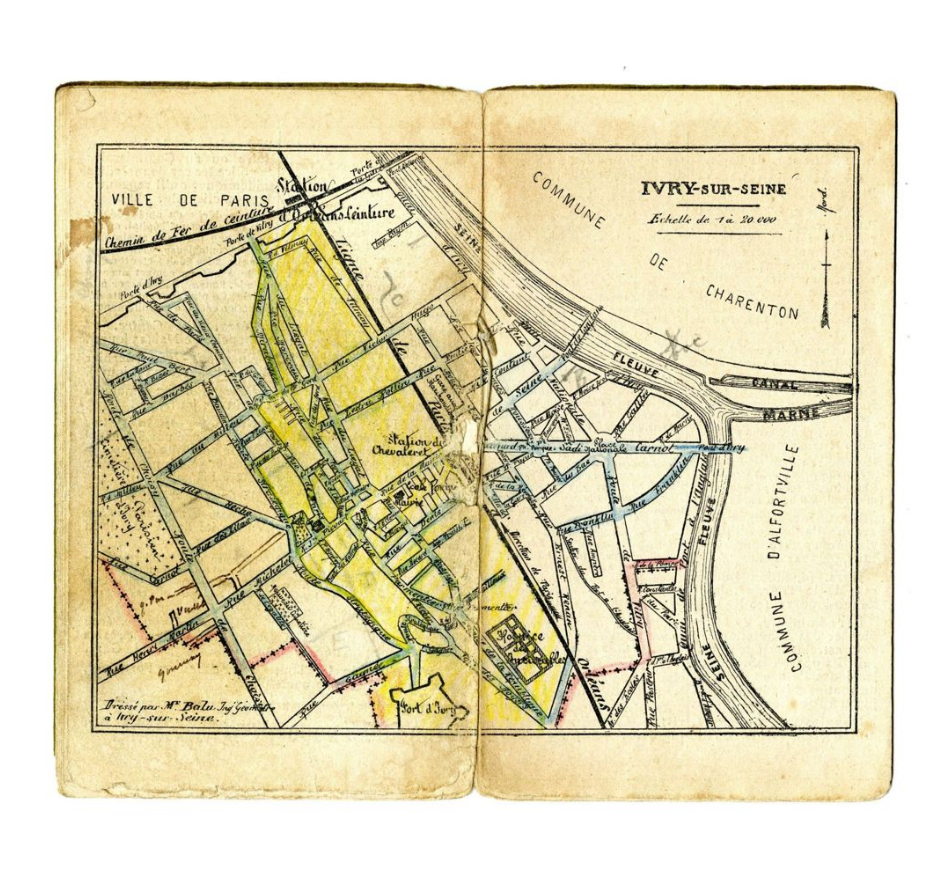

Fig. 1. Petit Guide Ivryen, 7th ed. (Ivry-sur-Seine: R. Aubert, 20th century), 14–15; copy from Archives municipals d’Ivry-sur-Seine

Fig. 1. Petit Guide Ivryen, 7th ed. (Ivry-sur-Seine: R. Aubert, 20th century), 14–15; copy from Archives municipals d’Ivry-sur-Seine

Fig. 2. Jean-Baptiste-Armand Guillaumin, Sunset at Ivry, 1873, oil on canvas, 25 5/8 x 31 7/8 in. (65 x 81 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris, RF 1951 34

Fig. 2. Jean-Baptiste-Armand Guillaumin, Sunset at Ivry, 1873, oil on canvas, 25 5/8 x 31 7/8 in. (65 x 81 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris, RF 1951 34

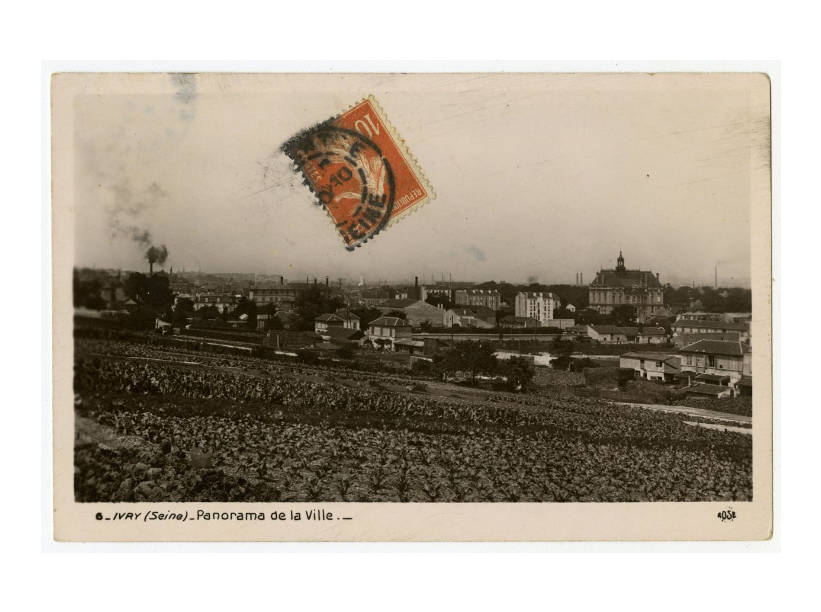

Fig. 3. View of Ivry-center, 1917, postcard, published by Rose, Municipal Archives of Ivry-sur-Seine, 2 Fi 1034

Fig. 3. View of Ivry-center, 1917, postcard, published by Rose, Municipal Archives of Ivry-sur-Seine, 2 Fi 1034

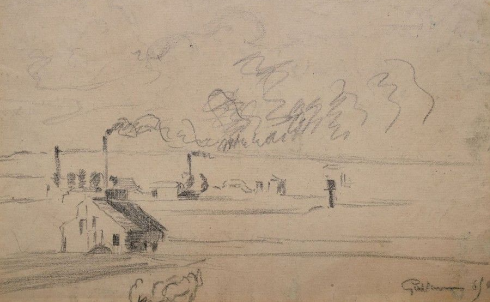

Fig. 4. Armand Guillaumin, Landscape at Ivry, 1869, black pencil on beige paper, 8 1/8 x 12 3/8 in. (20.5 x 31.5), private collection

Fig. 4. Armand Guillaumin, Landscape at Ivry, 1869, black pencil on beige paper, 8 1/8 x 12 3/8 in. (20.5 x 31.5), private collection

A promised gift of Robert L. Bloch, Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine is newly recognized as an important example of Guillaumin’s early development as a landscape artist. Indeed, the painting was featured in a 2021 exhibition organized by the Nelson-Atkins entitled Among Friends: Guillaumin, Cezanne, Pissarro, highlighting the artist’s creativity, exchange, and friendship with Cezanne and Pissarro.15Among Friends: Guillaumin, Cezanne, Pissarro was held at the Nelson Atkins Museum of Art from February 12 to January 23, 2022. No catalogue was produced.

Notes

-

Guillaumin was featured in three solo exhibitions by gallerist Paul Durand-Ruel in the years 1894, 1896, and 1898. See Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Paul Durand-Ruel: Memoirs of the First Impressionist Art Dealer, 1831–1922 (Paris: Flammarion, 2014), 213, 216–18.

-

Félix Fénéon, “Les Impressionnistes en 1886,” La Vogue (1886): 395. “Et ce coloriste furieux, ce beau peintre de paysages gorgés de sèves et haletants, a restitué à toutes ses figures humaines une robuste et placide animalité” (“And this furious colorist, this beautiful painter of breathless and sap-drenched landscapes, has restored to all his human figures a robust and placid animality”). Translation by the author.

-

See, for example, Denis Coutagne, Cézanne and Paris, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la RMN-Grand Palais, 2011); Felix Kramer, Monet and the Birth of Impressionism, exh. cat. (Munich: Prestel, 2015); and Alexander Babin and Albert Grigorevich Kostenevich, Impressionism: Sensation and Inspiration: Highlights from the Hermitage, exh. cat. (Amsterdam: Museumshop Hermitage Amsterdam, 2012).

-

The Nelson-Atkins landscape entered the collection of Robert Bloch in June 1989, but it was not exhibited in public until 2007, when it was included in an exhibition at the Nelson Atkins Museum of Art. See Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 14, 74–78, 158. The Nelson-Atkins landscape is also not reproduced in the artist’s catalogue raisonné: G. Serret and D. Fabiani, Armand Guillaumin 1841–1927 (Paris: Mayer, 1971).

-

Christopher Gray, “1841–1869: Beginnings,” in Armand Guillaumin (Chester, CT: Pequot Press, 1972), 2. See also Marco-Edo Tralbaut, Armand Guillaumin (1841–1927): En famille et sur le motif (Antwerp: Peré, 1971).

-

Charles Louis Borgmeyer, “Armand Guillaumin,” Fine Arts Journal 33, no. 5 (November 1915): 465–66. For more on Guillaumin’s years at the Académie Suisse, see Christophe Duvivier, Armand Guillaumin: Les années impressionnistes, exh. cat. (Aulnay-sous-Bois: Presses de Suisse, 1991).

-

For the Paris Orléans railroad timetables, see Petit Guide Ivryen, 7th ed. (Ivry-sur-Seine: R. Aubert, n.d.), http://cabinetdecuriosites.ivry94.fr/a/164/petit-guide-ivryen.

-

For more on the history of Ivry-sur-Seine, see Ivry-Centre, Transformation(s) d’un quartier XVIIe–XXe siècles, exh. cat. (Ivry-sur-Seine: Municipal archives of Ivry-sur-Seine, 2017), http://cabinetdecuriosites.ivry94.fr/r/59/ivry-centre-transformation-s-d-un-quartier-xviiie-xxe-siecle.

-

James H. Rubin identified five of these works, excluding the Nelson-Atkins painting, as the first concentrated works by an Impressionist on a clearly industrial motif. See James Rubin, “Factories and Work Sites,” in Impressionism and Modern Landscape: Productivity, Technology, and Urbanization from Manet to Van Gogh (Berkeley: University of California, 2008), 132–34, 216n43.

-

A postcard depicts the route that ran from Fort de Bicêtre to Fort d’Ivry. See Ivry-Centre, Transformation(s) d’un quartier.

-

Gray, “1841–1869: Beginnings,” 3.

-

In 1874, Guillaumin and Cezanne participated in the first Impressionist exhibition. In the catalogue, both artists listed their address as 120 Rue de Viaugirard. See Catalogue de la première Exposition de Peinture par MM. Caillebotte, Cals, Cézanne, Cordey, Degas, Guillaumin, Jacques-François, Lamy, Levert, Maureau, C. Monet, B. Morisot, Piette, Pissarro, Renoir, Rouart, Sisley, Tillot, exh. cat. (Paris: Imprimerie E. Capiomont et V. Renault, 1877), 9, 11 [repr., in Theodore Reff, ed., Modern Art in Paris: Two-Hundred Catalogues of the Major Exhibitions Reproduced in Facsimile in Forty-Seven Volumes, vol. 23, Impressionist Group Exhibitions (New York: Garland, 1981), unpaginated]. The two became neighbors a year later: in January 1875, Cezanne moved to 15 Quai d’Anjou, while Guillaumin lived at no. 13. For more on this, see John Rewald’s chapter, “Cézanne and Guillaumin,” in Études d’art Français offertes a Charles Sterling (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1975), 344.

-

For more on Guillaumin’s friendship and close working relationship with Cezanne, see James H. Rubin’s chapter, “Armand Guillaumin and Paul Cézanne in Ile-de-France,” in Coutagne, Cézanne and Paris, 64–71. See also Rewald, “Cézanne and Guillaumin,” 346–47; and Armand Guillaumin: l’Impressioniste, ami de Cézanne et Van Gogh, exh. cat. (Geneva: Musée d’Art Moderne, 1995).

-

For more on Cezanne’s constructive stroke and Guillaumin’s possible influence, see Rewald, “Cézanne and Guillaumin,” 346–47. See also Rubin, “Armand Guillaumin and Paul Cezanne in Ile-de-France,” 67–68.

-

Among Friends: Guillaumin, Cezanne, Pissarro was held at the Nelson Atkins Museum of Art from February 12 to January 23, 2022. No catalogue was produced.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Diana M. Jaskierny, “Armand Guillaumin, Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine, ca. 1874,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.621.2088.

MLA:

Jaskierny, Diana M. “Armand Guillaumin, Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine, ca. 1874,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.621.2088.

Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine was completed on a somewhat coarse, open, plain-weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas.1Openings are only visible in areas where there is no ground or priming material. The tacking margins are preserved and retain important details about how the support was prepared prior to painting, with pronounced cuspingcusping: A scalloped pattern along the canvas edges that relates to how the canvas was stretched. Primary cusping reveals where tacks secured the canvas to the support while the ground layer was applied. Secondary cusping can form when a pre-primed canvas is re-stretched by the artist prior to painting. on all tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. and the edges of the picture planepicture plane: The two-dimensional surface where the artist applies paint.. The canvas was then prepared with an opaque white or slightly off-white ground layerground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer., and in areas where the paint layer was thinly applied, the coarse texture of the ground layer is visible (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph with raking light, showing the coarse ground layer texture found in the lower right quadrant in Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine (ca. 1874)

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph with raking light, showing the coarse ground layer texture found in the lower right quadrant in Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine (ca. 1874)

Fig. 7. Detail of the left side turnover edge and ground layer application in normal light (left) and raking light (right), with a white arrow pointing toward the ground layer edge bead, in Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine (ca. 1874)

Fig. 7. Detail of the left side turnover edge and ground layer application in normal light (left) and raking light (right), with a white arrow pointing toward the ground layer edge bead, in Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine (ca. 1874)

Fig. 8. Infrared photograph of the left-side horizon with white arrows pointing toward parallel underdrawing lines in Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine (ca. 1874)

Fig. 8. Infrared photograph of the left-side horizon with white arrows pointing toward parallel underdrawing lines in Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine (ca. 1874)

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of exposed ground and charcoal underdrawing (see white arrows) beside the large smokestack in Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine (ca. 1874)

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of exposed ground and charcoal underdrawing (see white arrows) beside the large smokestack in Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine (ca. 1874)

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of gray-blue underpainting (see black arrow) near the horizon in Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine (ca. 1874)

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of gray-blue underpainting (see black arrow) near the horizon in Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine (ca. 1874)

Fig. 11. Detail of red-roofed building and background, illustrating glimpses of exposed ground in Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine (ca. 1874)

Fig. 11. Detail of red-roofed building and background, illustrating glimpses of exposed ground in Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine (ca. 1874)

Fig. 12. Detail of the central figure and horses in Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine (ca. 1874)

Fig. 12. Detail of the central figure and horses in Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine (ca. 1874)

Fig. 13. Detail of hatching on the stone wall in Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine (ca. 1874)

Fig. 13. Detail of hatching on the stone wall in Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine (ca. 1874)

Fig. 14. Detail of clouds in Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine (ca. 1874)

Fig. 14. Detail of clouds in Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine (ca. 1874)

Fig. 15. Detail of the right clothesline illustrating wet-over-dry paint application in Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine (ca. 1874)

Fig. 15. Detail of the right clothesline illustrating wet-over-dry paint application in Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine (ca. 1874)

Notes

-

Openings are only visible in areas where there is no ground or priming material.

-

The distance between the turnover edgeturnover edge: The point at which the canvas begins to wrap around the stretcher, at the junction between the picture plane and tacking margin. See also foldover edge. and edge of the ground layer varies between each of the four sides, ranging from two to five millimeters.

-

Since Guillaumin was known to use unprimed canvases at times, it is possible that the artist purchased this canvas unprimed and added the priming layer himself. Anthea Callen, The Art of Impressionism: Painting Technique and the Making of Modernity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 67.

-

Pascal Labreuche, “The Industrialisation of Artists’ Prepared Canvas in Nineteenth-Century Paris—Canvas and Stretchers: Technical Developments Up to the Period of Impressionism,” Zeitschrift für Kunsttechnologie und Konservierung 22, no. 2 (2008): 319.

-

While the existing stretcher appears older and could be contemporaneous to the painting, it is unknown if it is the original stretcher or an early replacement from when the painting was lined.

-

Similar brief underdrawings were found in Guillaumin’s The Sea at Saint-Palais (1892; Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne) and Rock at Baumette Point (1893; Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne). While these underdrawings were also composed of few lines to place compositional elements, in these paintings the underdrawings are described as being composed of fine particles. Caroline von Saint-George and Annegret Volk, “Armand Guillaumin—The Sea at Saint-Palais, Brief Report on Technology and Condition,” in Research Project Painting Techniques of Impressionism and Postimpressionism, 2008, https://forschungsprojekt-impressionismus.de/bilder/pdf/7_e.pdf. See also Caroline von Saint-George and Annegret Volk, “Armand Guillaumin–Rock at Baumette Point, Brief Report on Technology and Condition,” in Research Project Painting Techniques of Impressionism and Postimpressionism, 2008, https://forschungsprojekt-impressionismus.de/bilder/pdf/8_e.pdf.

-

No underdrawing was found to establish the structures in the foreground, any figures, or the larger structures in the far-right background.

-

Forrest R. Bailey, June 13, 1978, treatment report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 27-1989.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Armand Guillaumin, Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine, ca. 1874,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.621.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Armand Guillaumin, Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine, ca. 1874,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.621.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Armand Guillaumin, Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine, ca. 1874,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.621.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Armand Guillaumin, Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine, ca. 1874,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.621.4033.

With Adolfo Bullrich y Cía. Ltda. S.A., Buenos Aires, by September 20–23, 1971;

Purchased from Bullrich, Arte y Antigüedades, September 20–23, 1971, lot 27, as Paisaje de los alrededores de Paris [1];

Saussure Collection, Paris;

Galerie Schmit, Paris, by 1974–June 8, 1978 [2];

Purchased from Galerie Schmit, Paris, by Mr. and Mrs. Robert L. Bloch, June 8, 1978 [3];

Notes

[1] Seller and buyer is currently unknown, but see annotated sales catalogue in the Collection of Frick Art Reference Library, New York, which says “3800” in the left margin.

[2] For purchase date, see correspondence from Robert Schmit to Robert Bloch, June 8, 1978, NAMA curatorial files.

[3] The painting was purchased from Galerie Schmidt by Robert Bloch in 1978 with his first wife Lisa. Robert Bloch and his second wife, Barbara, have promised the painting in honor of his parents, Henry and Marion Bloch, and the 75th anniversary of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. See correspondence from Robert Bloch to Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Louis L. and Adelaide C. Ward Senior Curator, European Arts, NAMA, August 25, 2020, NAMA curatorial object files.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Armand Guillaumin, Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine, ca. 1874,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.621.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Armand Guillaumin, Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine, ca. 1874,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.621.4033.

Armand Guillaumin, The Seine at Ivry, ca. 1869, oil on wood, 12 x 15 1/2 in. (30.5 x 39.5 cm), Musée du Petit Palais, Geneva.

Armand Guillaumin, Forges at Ivry, ca. 1873, oil on canvas, 23 5/8 x 39 3/8 in. (60 x 100 cm), private collection, Lausanne; illustrated in G. Serret and D. Fabiani, Armand Guillaumin 1841–1927 (Paris: Mayer, 1971), no. 17.

Armand Guillaumin, Forges at Ivry in the Snow, ca. 1873, oil on canvas, 13 x 18 1/8 in. (33 x 46 cm), private collection; illustrated in G. Serret and D. Fabiani, Armand Guillaumin 1841–1927 (Paris: Mayer, 1971), no. 18.

Armand Guillaumin, Sunset at Ivry, 1873, oil on canvas, 25 5/8 x 31 7/8 in. (65 x 81 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

Armand Guillaumin, Snow at Ivry, 1873, oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 28 3/4 in. (52 x 73 cm), Musée du Petit Palais, Geneva.

Preparatory Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Armand Guillaumin, Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine, ca. 1874,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.621.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Armand Guillaumin, Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine, ca. 1874,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.621.4033.

Armand Guillaumin, Landscape, undated, pastel, 13 3/4 x 19 3/4 in. (35 x 50 cm), location unknown; illustrated in Tableaux modernes et du XIXe siècle (Versailles: Palais des Congrès, November 26, 1978), unpaginated.

Armand Guillaumin, Landscape with Factory Chimneys, undated, pastel, 8 5/16 x 14 13/16 in. (21 x 37.5 cm), location unknown; illustrated in Tableaux Modernes (Paris: Sotheby’s, December 16, 2012), unpaginated.

Armand Guillaumin, Landscape at Ivry, 1869, charcoal and black chalk, location unknown; illustrated in Christopher Gray, Armand Guillaumin (Chester, CT: Pequot Press, 1972), 3.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Armand Guillaumin, Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine, ca. 1874,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.621.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Armand Guillaumin, Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine, ca. 1874,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.621.4033.

Naissance de l’impressionnisme, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Bordeaux, May 3–September 1, 1974, no. 92, as Paysage d’Ile-de-France.

VIIIe Biennale des Antiquaires, Galerie Schmit, Paris, September 23–October 10, 1976, no. 20, as Paysage d’Ile-de-France.

Aspects de la Peinture Française: XIXe et XXe Siècles, Galerie Schmit, Paris, May 10–June 30, 1978, no. 31, as Paysage d’Ile-de-France.

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 12, as Landscape, Île de France (Paysage d’Île de France).

Magnificent Gifts for the 75th, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, February 13–April 4, 2010, no cat.

Impressionist France: Visions of Nation from Le Gray to Monet, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, October 19 2013–February 9, 2014; The Saint Louis Art Museum, March 18–July 14, 2014, no. 139, as Landscape, Île de France.

Among Friends: Guillaumin, Cezanne, and Pissarro, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, January 28, 2021–January 23, 2022, no cat.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Armand Guillaumin, Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine, ca. 1874,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.621.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Armand Guillaumin, Landscape, Ivry-sur-Seine, ca. 1874,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.621.4033.

Arte y Antigüedades (Buenos Aires: Adolfo Bullrich y Cía. Ltda. S.A., 1971), unpaginated, (repro.), as Paisaje de los alrededores de Paris.

Advertisement, Connoisseur 177, no. 714 (August 1971): 19, (repro.), as Paysage aux environs de Paris.

Naissance de l’impressionnisme, exh. cat. (Bordeaux, France: Musée des Beaux-Arts, 1974), 130–31, (repro.), as Paysage d’Ile [sic] -de-France.

VIIIe Biennale des Antiquaires, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Schmit, 1976), unpaginated, (repro.), as Paysage d’Ile [sic] -de-France.

Aspects de la Peinture Française: XIXe et XXe Siècles, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Schmit, 1978), 33, (repro.), as Paysage d’Ile [sic] -de-France.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 14, 74–78, 158, (repro.), as Landscape, Île de France (Paysage d’Île de France).

“75 Nelson-Atkins Patrons Give 400 Extraordinary Works of Art to Commemorate Museum’s 75th Anniversary,” Art and Artworks (February 2008): unpaginated, as Landscape, Ile [sic] de France (Paysage d’Ile [sic] de France).

“A 75th Anniversary Celebrated with Gifts of 400 Works of Art,” Art Tattler International (February 2008): unpaginated, (repro.), as Landscape, Île de France (Paysage d’Île de France).

Alice Thorson, “Gift will leave lasting impression,” Kansas City Star 130, no. 143 (February 7, 2010): G2.

Simon Kelly and April M. Watson, Impressionist France: Visions of Nation from Le Gray to Monet, exh. cat. (St. Louis, MO: St. Louis Art Museum, 2013), 25, 236–37 (repro.), as Landscape, Île de France.

Alice Thorson, “Nelson’s ‘Impressionist France’ offers an insider’s guide to a country in transition,” Kansas City Star (November 8, 2013): https://www.kansascity.com/news/local/article331233/Nelsons-Impressionist-France-offers-an-insiders-guide-to-a-country-in-transition.html, as Landscape, Ile [sic] de France.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 79, (repro.), as Landscape, Île de France.

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” Forward (March 14, 2017), http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca/ [repr., in Menachem Wecker, “Kansas City Collection Is A Chip Off the Old Bloch,” Forward (March 17, 2017): 20–22], as Landscape.

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “A Refuge of Peaceful Meditation,” KC Studio 12, no. 5 (September/October 2020): 74–75, (repro.), as Landscape, Île de France.