Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Allison Perelman, “Pierre Bonnard, Still Life with Guelder Roses, 1892; reworked 1929,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.704.5407.

MLA:

Perelman, Allison. “Pierre Bonnard, Still Life with Guelder Roses, 1892; reworked 1929,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.704.5407.

In December 1891, Pierre Bonnard participated in the exhibition Peintres impressionnistes et symbolistes (Impressionist and Symbolist Painters) at the Parisian gallery Le Barc de Boutteville. This group show was the first joint venture organized around a young circle of artists who called themselves the NabisNabis: Nabi is the Hebrew word for prophet. Founded by Paul Sérusier, the Nabis were a group of Post-Impressionist painters active in France from 1888 to around 1900. Utilizing a simplified style of thick, undulating contours and flat planes of vibrant color inspired by Synthetism, the Nabis rejected naturalistic depictions of reality and relied instead on metaphor and purely formal devices to evoke feelings and subject matter. An experimental group of painters, the Nabi created stage sets for Symbolist theatre productions and painted on unconventional supports such as velvet and cardboard. See also Synthetism..1The circle did not publicly refer to itself collectively as “les Nabis” until late in the 1890s. Véronique Serrano, “Chronology: 1867–1947,” in Pierre Bonnard: Painting Arcadia, ed. Guy Cogeval and Isabelle Cahn, exh. cat. (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2015), 313. Although Bonnard was a member, he distanced himself from any collective allegiance. In an article on the exhibition, he gave a rare statement about his artistic identity: “I do not belong to any school. I am only looking to do something personal.”2“Je ne suis d’aucune école. Je cherche uniquement à faire quelque chose de personnel.” Bonnard quoted in Jacques Daurelle, “Chez les jeunes peintres,” L’Écho de Paris 8, no. 2779 (December 28, 1891): 2.

Painted the following year, Still Life with Guelder Roses reflects this pivotal moment in Bonnard’s career, as he experimented with techniques and aesthetics in a quest to develop his own style. The work depicts an arrangement of at least fifteen clusters of yellow-white blossoms against a field of loosely defined leaves in various shades of green. The foliage emerges from a white vase, but the setting for the still life is not defined; rather, the bouquet seems to float on a flat backdrop of gray-brown. In the bottom left corner, the suggestion of a crumpled yellow cloth—which dissolves into loose brushstrokes of whites, grays, and dark brown—hints at a tabletop that otherwise does not appear. In 1929, the artist returned to the canvas,3Jean and Henry Dauberville record the painting’s date as 1892, but retouched by the artist in 1929, when Bonnard added the signature. See Jean Dauberville and Henry Dauberville, Bonnard: Catalogue Raisonné de l’Œuvre Peint, 1888–1905 (Paris: Éditions J. et H. Bernheim-Jeune, 1965), no. 31, p. 1:107. adding dabs of color over his original marks without altering the composition. The still life thus offers insight into the development of Bonnard’s personal aesthetic at an early stage of his career as well as its later evolution.

Beginning in 1886–87, Bonnard trained at the Académie Julian, an established and progressive art school in Paris. In this same period, he also enrolled at the prestigious yet conservative École des Beaux-Arts. Although Bonnard would later admit to only “intermittent” attendance at these institutions, his time there proved to be formative for his artistic career due to the people he met.4Antoine Terrasse, Bonnard: Shimmering Color, trans. Laurel Hirsch (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2000), 15. At the Académie Julian, he befriended other young artists, notably Maurice Denis (1870–1943), Henri-Gabriel Ibels (1867–1936), Paul Ranson (1862–1909), and Paul Sérusier (1864–1927). They began to refer to themselves collectively as the Nabis, a French transliteration of the Hebrew word for “prophets” (Nebiim). Although their individual aesthetics differed, they shared a desire to reject convention and instead seek a subjective vision of the world. Likewise, the Nabis challenged traditional artistic hierarchies by experimenting across media and venturing into the decorative arts. In 1889, the circle grew with the addition of Ker-Xavier Roussel (1867–1944) and Edouard Vuillard (1868–1940); Vuillard and Bonnard formed a close friendship. Bonnard joined in the meetings, exhibitions, and shared projects of the Nabis, but he remained an independent spirit and avoided the theorizing practices of others.5One of Bonnard’s first biographers, Thadée Natanson, claimed that the artist never participated in the theoretical conversations of the other Nabis, notably Denis and Sérusier. Sarah Whitfield, “Fragments of an Identical World,” in Bonnard, ed. Sarah Whitfield, exh. cat. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998), 9.

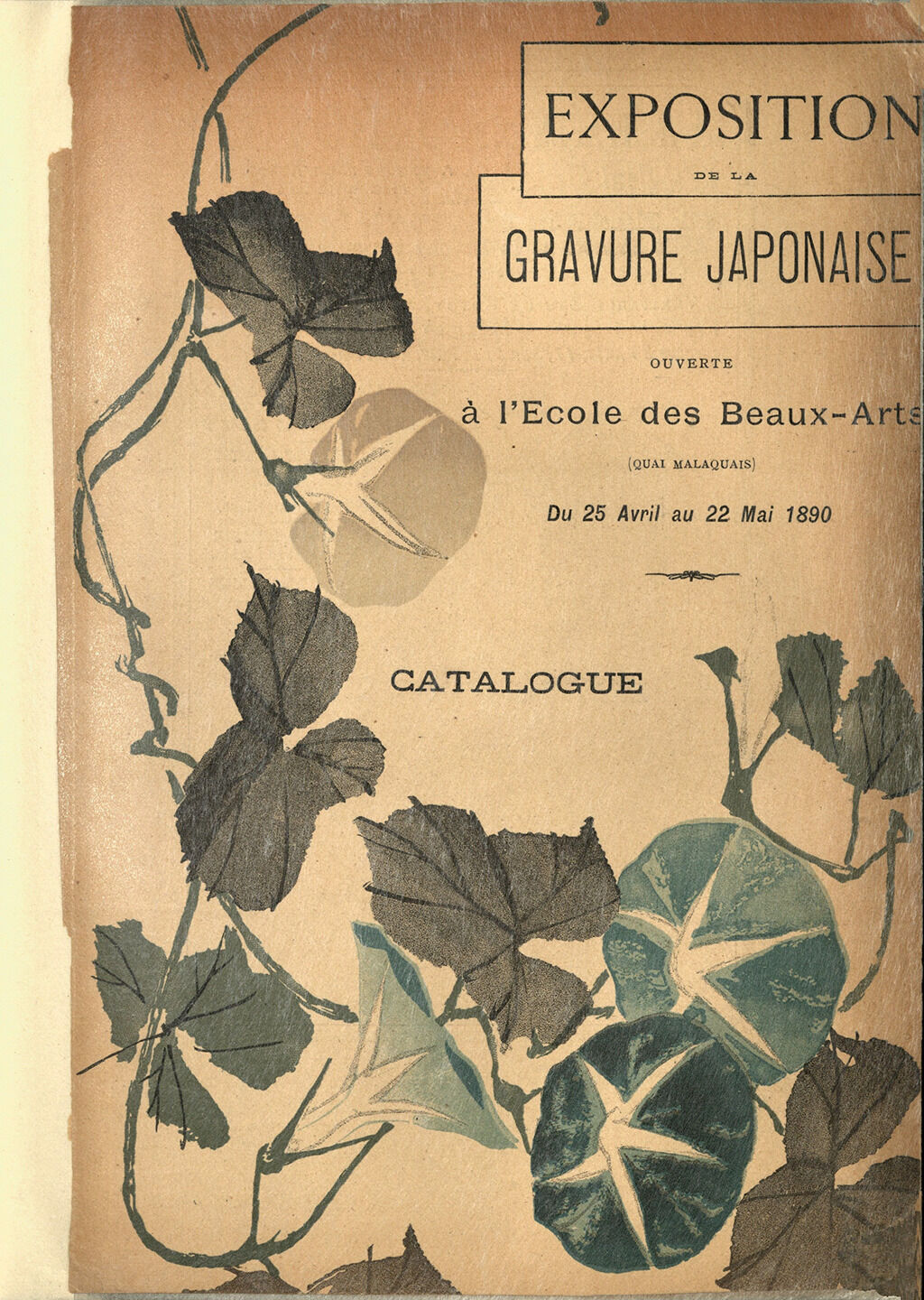

In May 1890, Bonnard visited La Gravure japonaise (Japanese Prints) at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris (Fig. 1). This exhibition featured 725 woodblock prints and 421 illustrated books from Japan.6Elsa M. Smithgall and Lisa Lipinski, “Chronology,” in Pierre Bonnard: Early and Late, ed. Elizabeth Hutton Turner, exh. cat. (London: Philip Wilson in association with the Phillips Collection, 2002), 28. The vibrant prints fascinated Bonnard, who found in them a visual style that was distinct from European conventions for composition and treatment of space. He began collecting Japanese prints, particularly so-called crépons (chirimen-e), which he could purchase cheaply in Paris.7These prints were produced on Japanese paper in the same manner as standard woodblock prints and subsequently pressed to create a crinkled texture, reminiscent of fabric. See, for example, Kosode fragment, 1800–49, white silk crepe (chirimen) with brush drawing and resist dyeing, 9 3/4 × 15 3/4 in. (24.77 × 40.01 cm), Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 31-100/48, https://art.nelson-atkins.org/objects/27676. As he later recounted:

In the department store, for one or two pennies, I found crépons or crumpled rice papers in astonishing colors. I filled the walls of my room with this naïve and gaudy art. . . . I understood immediately from those crude images that color could express all things without needing modeling or relief.8“C’est là que je trouvais pour un ou deux sous des crépons ou des papiers de riz froissés des couleurs étonnâtes. Je remplis les murs de ma chambre de cette imagerie naïve et criarde. . . . J’avais compris au contact de ces frustes images populaires que la couleur pourrait comme ici exprimer toutes choses sans besoin de relief ou modèle.” Bonnard quoted in Gaston Diehl, “Bonnard dans son univers enchanté,” Comœdia 3, no. 106 (July 10, 1943): 6; translated in Elizabeth Hutton Turner, “The Imaginary Cinema of Pierre Bonnard,” in Turner, ed., Pierre Bonnard: Early and Late, 54.

The artist continually surrounded himself with these inspiring works; photographs of his studios up to the end of his life reveal the prints he kept pinned to his walls.9Ursula Perucchi-Petri, “Japonisme in Bonnard’s Early and Late Work,” in Turner, Pierre Bonnard: Early and Late, 191. Although he was participating in the larger cultural movement of Japonisme—a widespread enthusiasm for Japanese art, culture, and aesthetics in Europe during the second half of the nineteenth century—Bonnard was singled out by critics for his success in transmuting his inspiration into a decorative style all his own.10Critic Félix Fénéon referred to Bonnard as “très japonard” (very Japanese). Félix Fénéon, “Au pavillon de la ville de Paris: Société des artistes indépendants,” Le Chat noir 11, no. 533 (April 2, 1892): 1932; see also Georges-Albert Aurier, “Beaux-Arts: Les Symbolistes,” Revue Encyclopédique 2, no. 32 (April 1, 1892): 485.

Initially, he applied the lessons he derived from Japanese prints into his own graphic work, but he soon adapted his nascent aesthetic to painting as well. A year before he created the Nelson-Atkins canvas, Bonnard painted an arrangement of guelder roses that demonstrates a more direct interpretation of Japanese prints (Fig. 2). The composition consists of eight clusters of white blooms entwined with leaves and stems. The artist accentuated the flatness of the picture plane with his unmodulated colors; only the slight variations in the shades of green give any suggestion of depth. He further emphasized the two-dimensionality of the canvas with the solid-colored background, a common feature in some of the prints he would have seen at the exhibition the year before. The red butterfly in the top right corner is another motif borrowed from Japanese woodblock prints.11Nicholas Watkins, Bonnard (London: Phaidon, 1994), 25.

Guelder roses are also present in Bonnard’s Design for a Fan: Women and Flowers (Fig. 3). On the right half, the white blossoms and green leaves appear against another solid backdrop in a lighter tone of green. On the left side, three fashionable women—along with two dogs and a cat—present the artist with an opportunity to play with the patterns and shapes of their clothing, hats, and hair. At the center, the smaller figures of a couple and a child provide the only suggestion of spatial recession. This watercolor is one of a handful of designs for fans that Bonnard produced in the early 1890s.12Along with his fellow Nabis, Bonnard sought to merge art and life with forays into the decorative arts, creating fans, screens, stained glass, and more. Stephen Ongpin, An Exhibition of Master Drawings. . . ., exh. cat. (New York: Colnaghi, 1998), 59. For more on the decorative projects of Bonnard and the other Nabis, see Gloria Groom, ed., Beyond the Easel: Decorative Painting by Bonnard, Vuillard, Denis, and Roussel, 1890–1930, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2001). Similar white flowers appear in a multifigural composition from the same year, Afternoon in the Garden (Fig. 4). This canvas demonstrates the progression of Bonnard’s decorative aesthetic, which prioritized color and pattern over naturalistic representation and even legibility. The faces of his sister, nephew, and other family members are obscured by foliage, a red fan, and nebulous shapes along the bottom register.13Katherine M. Kuenzli, “Theorizing the Nabis: Julius Meier-Graefe and the Making of a Modern Aesthetic,” in Bonnard to Vuillard: The Intimate Poetry of Everyday Life, The Nabi Collection of Vicki and Roger Sant, ed. Elsa Smithgall, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: Phillips Collection, 2019), 31. The artist’s exaggerated approach to color and line merged foreground and background to create an overall sense of rhythm. Bonnard exhibited Afternoon in the Garden at his first showing at the Salon des Indépendants (March 20–April 27, 1891), to which he submitted five paintings and four decorative panels.14The other exhibited paintings were Andrée Bonnard with Her Dogs (1889; private collection), On the Parade Ground (1890; private collection), The Good Dog (1891; private collection), and Study of a Cat (1891; private collection). Although he originally envisioned the four panels of Women in the Garden (1891; Musée d’Orsay, Paris) as a screen, Bonnard separated them, framed them individually, and hung them on the wall as a group. See Terrasse, Bonnard: Shimmering Color, 20. Bonnard’s avant-garde works challenged the public, and one critic characterized them as “risky ventures” that “defy all criticism.”15“Les envois de M. Bonnard et de M. Wilhumsen, semblent des gageures et défient toute critique” (The submissions of M. Bonnard and of M. Wilhumsen seem to be risky ventures and defy all criticism). Jules Antoine, “Critique d’art: Pavillon de la Ville de Paris. Exposition des Artistes Indépendants,” La Plume 3, no. 49 (May 1, 1891): 157. At this time, the artist was deliberately seeking to develop new directions in his art. By September of the following year, he wrote to Vuillard that he was finally making progress: “Painting, particularly in oil, has kept me very busy; it is going slowly, very timidly, but I believe I am on the right track.”16“La peinture à l’huile entre autres m’a beaucoup occupé; cela va bien doucement, bien timidement mais je crois être sur la bonne voie.” Pierre Bonnard, Le Grand-Lemps, to Edouard Vuillard, September 19, 1892, in Antoine Terrasse, ed., Bonnard/Vuillard correspondance (Paris: Gallimard, 2001), 23.

The Nelson-Atkins painting and another, very similar canvas of the same year (Fig. 5) belong to the transitional moment when the more linear style of the late 1880s and early 1890s began to give way to a more painterly aesthetic. Bonnard adopted a looser, more varied brushstroke that often did not delineate the contours of his forms but rather blurred the edges. In both works, the artist depicted a large bouquet of guelder roses and leaves bursting from the neck of a white ceramic vase, set against a wash of gray-brown. The two versions employ the same palette of whites, grays, browns, and yellows featured in many of his works from the 1890s, particularly his lithographs.17Examples of this palette in his graphic work can be found in the Nelson-Atkins collection. See, for example, La Revue blanche, 1894, lithograph in four colors on off-white wove paper, framed: 34 1/8 x 26 3/4 x 3/4 in. (86.7 x 67.9 x 1.9 cm), Bequest of Donald D. Jones, 2001.3.168, https://art.nelson-atkins.org/objects/32282/la-revue-blanch; and Street at Night: Rain, 1899, color lithograph, image: 10 1/16 x 13 7/8 in. (25.6 x 35.2 cm), sheet: 16 x 21 in. (40.6 x 53.3 cm), Purchase: acquired through the generosity of an anonymous donor, F78-3/3, https://art.nelson-atkins.org/objects/7673/street-at-night–rain. The painting from a private collection appears even sketchier than Still Life with Guelder Roses. In the former, the gray background does not cover the canvas but rather envelops the bouquet like a halo, surrounded by the exposed, brownish ground. Indistinct shapes in light yellow, silver, and red animate the composition without giving clear form to the setting. The Nelson-Atkins canvas may have once resembled the other version more than it does today; Bonnard returned to it almost forty years later and added strokes of color that increased the sense of dimensionality.

Technical analysis offers insight into the artist’s original working process as well as later changes to the painting. Bonnard initially sketched the still life on the canvas with charcoal, traces of which can be identified under magnification.18While glimpses of charcoal are visible beneath and between paint strokes in certain areas of the composition, infrared reflectography at 1950 nanometers was unable to provide a fuller view of the underlying charcoal sketch. See accompanying technical entry by Mary Schafer and John Twilley, specifically paragraph 1 and figure 10. He then built up the surface all at once, painting the bouquet and the background at the same time. Next, Bonnard used pen and ink on top of the partially dried oils to draw short, curling lines on the blossoms and additional lines on the vase and at the edge of the tablecloth.19Schafer and Twilley, technical entry. Similar lines appear in the blooms of Flowers: Snowballs (see Fig. 2) and Afternoon in the Garden (see Fig. 4), where they remain visible today. In the Nelson-Atkins still life, however, some of the pen-and-ink lines were later covered by gray paint, concealing them. Sometime in 1929, Bonnard added dabs of blue-gray and yellow-gray to the blossoms, making them appear more dimensional, although he did not make any compositional changes.20Schafer and Twilley, technical entry. He also applied a line of orange paint to the contours of the fabric, covering the line of ink and heightening the sense of shadow and modeled form. It was not unusual for the artist to revisit and retouch his canvases, even after a period of four decades. “Bonnard likes to revisit his old paintings,” remarked the critic Georges Besson, in what might be an apocryphal anecdote,

At the Grenoble Museum and then at the Luxembourg, he managed to keep an eye out for a guard passing from one room to another, to take a tiny box filled with two or three paint tubes and a small brush out of his pocket, and to furtively “improve” [one of his paintings] with a few touches.21“Bonnard aime à reprendre ses anciens tableaux. Au musée de Grenoble puis au Luxembourg, il lui arriva de guetter le passage d’un gardien d’une salle à l’autre, de sortir d’une poche une minuscule boîte garnie de deux ou trois tubes et d’un bout de pinceau, ‘d’améliorer’ furtivement de quelques touches.” George Besson, “Lettre à Pierre Betz,” in “Bonnard,” special issue, Le Point: Revue artistique et littéraire 4, no. 24 (1943): 46, quoted in Antoine Terrasse, Bonnard: The Colour of Daily Life (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000), 126.

With the later modifications, Still Life with Guelder Roses speaks to the artist’s painterly style at both the beginning and late stages of his career, as he moved from the flatness of Japonisme to a more dimensional approach.

The still life remained in Bonnard’s studio until he gave it to a collector named Charancle.22Dauberville and Dauberville, Bonnard, no. 31, p. 1:107. It is unclear if the collector’s name is Bonis Charancle, Boris Charancle, or Denis Charancle. Further information and a more complete history of ownership is provided in this object’s provenance entry. It was later sold to financier and entrepreneur Léon-Georges Lévy (1891–1953).23After immigrating to the United States, he changed his name to Georges Lurcy. Frances Brent, “Visual Moment: The Compelling Odysseys of Looted Art,” Moment Magazine, September 9, 2021, https://momentmag.com/odysseys-of-looted-art-pierre-bonnard. In 1933, the painting was sold or traded to Jewish banker and philanthropist David David-Weill (1871–1952), a prolific art collector whose taste ranged from Neolithic Chinese objects to modern French painting. A decade later, the Nazis confiscated the painting and thousands of other artworks from David-Weill, ultimately transferring and storing them underground in a salt mine in Austria. In May 1945, Allied forces recovered the painting, and, by June 1946, it was returned to David-Weill. Still Life with Guelder Roses remained in the family, passing by inheritance to David-Weill’s wife and, subsequently, their heirs. In 1972, the family sold the work to Herman R. (1913–2006) and Helen (1914–2004) Sutherland of Mission Hills, Kansas, who gifted it to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in 2004.

Notes

-

The circle did not publicly refer to itself collectively as “les Nabis” until late in the 1890s. Véronique Serrano, “Chronology: 1867–1947,” in Pierre Bonnard: Painting Arcadia, ed. Guy Cogeval and Isabelle Cahn, exh. cat. (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 2015), 313.

-

“Je ne suis d’aucune école. Je cherche uniquement à faire quelque chose de personnel.” Bonnard quoted in Jacques Daurelle, “Chez les jeunes peintres,” L’Écho de Paris 8, no. 2779 (December 28, 1891): 2.

-

Jean and Henry Dauberville record the painting’s date as 1892, but retouched by the artist in 1929, when Bonnard added the signature. See Jean Dauberville and Henry Dauberville, Bonnard: Catalogue Raisonné de l’Œuvre Peint, 1888–1905 (Paris: Éditions J. et H. Bernheim-Jeune, 1965), no. 31, p. 1:107.

-

Antoine Terrasse, Bonnard: Shimmering Color, trans. Laurel Hirsch (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2000), 15.

-

One of Bonnard’s first biographers, Thadée Natanson, claimed that the artist never participated in the theoretical conversations of the other Nabis, notably Denis and Sérusier. Sarah Whitfield, “Fragments of an Identical World,” in Bonnard, ed. Sarah Whitfield, exh. cat. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998), 9.

-

Elsa M. Smithgall and Lisa Lipinski, “Chronology,” in Pierre Bonnard: Early and Late, ed. Elizabeth Hutton Turner, exh. cat. (London: Philip Wilson in association with the Phillips Collection, 2002), 28.

-

These prints were produced on Japanese paper in the same manner as standard woodblock prints and subsequently pressed to create a crinkled texture, reminiscent of fabric. See, for example, Kosode fragment, 1800–49, white silk crepe (chirimen) with brush drawing and resist dyeing, 9 3/4 × 15 3/4 in. (24.77 × 40.01 cm), Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 31-100/48, https://art.nelson-atkins.org/objects/27676.

-

“C’est là que je trouvais pour un ou deux sous des crépons ou des papiers de riz froissés des couleurs étonnâtes. Je remplis les murs de ma chambre de cette imagerie naïve et criarde. . . . J’avais compris au contact de ces frustes images populaires que la couleur pourrait comme ici exprimer toutes choses sans besoin de relief ou modèle.” Bonnard quoted in Gaston Diehl, “Bonnard dans son univers enchanté,” Comœdia 3, no. 106 (July 10, 1943): 6; translated in Elizabeth Hutton Turner, “The Imaginary Cinema of Pierre Bonnard,” in Turner, ed., Pierre Bonnard: Early and Late, 54.

-

Ursula Perucchi-Petri, “Japonisme in Bonnard’s Early and Late Work,” in Turner, Pierre Bonnard: Early and Late, 191.

-

Critic Félix Fénéon referred to Bonnard as “très japonard” (very Japanese). Félix Fénéon, “Au pavillon de la ville de Paris: Société des artistes indépendants,” Le Chat noir 11, no. 533 (April 2, 1892): 1932; see also Georges-Albert Aurier, “Beaux-Arts: Les Symbolistes,” Revue Encyclopédique 2, no. 32 (April 1, 1892): 485.

-

Nicholas Watkins, Bonnard (London: Phaidon, 1994), 25.

-

Along with his fellow Nabis, Bonnard sought to merge art and life with forays into the decorative arts, creating fans, screens, stained glass, and more. Stephen Ongpin, An Exhibition of Master Drawings. . . ., exh. cat. (New York: Colnaghi, 1998), 59. For more on the decorative projects of Bonnard and the other Nabis, see Gloria Groom, ed., Beyond the Easel: Decorative Painting by Bonnard, Vuillard, Denis, and Roussel, 1890–1930, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2001).

-

Katherine M. Kuenzli, “Theorizing the Nabis: Julius Meier-Graefe and the Making of a Modern Aesthetic,” in Bonnard to Vuillard: The Intimate Poetry of Everyday Life, The Nabi Collection of Vicki and Roger Sant, ed. Elsa Smithgall, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: Phillips Collection, 2019), 31.

-

The other exhibited paintings were Andrée Bonnard with Her Dogs (1889; private collection), On the Parade Ground (1890; private collection), The Good Dog (1891; private collection), and Study of a Cat (1891; private collection). Although he originally envisioned the four panels of Women in the Garden (1891; Musée d’Orsay, Paris) as a screen, Bonnard separated them, framed them individually, and hung them on the wall as a group. See Terrasse, Bonnard: Shimmering Color, 20.

-

“Les envois de M. Bonnard et de M. Wilhumsen, semblent des gageures et défient toute critique” (The submissions of M. Bonnard and of M. Wilhumsen seem to be risky ventures and defy all criticism). Jules Antoine, “Critique d’art: Pavillon de la Ville de Paris. Exposition des Artistes Indépendants,” La Plume 3, no. 49 (May 1, 1891): 157.

-

“La peinture à l’huile entre autres m’a beaucoup occupé; cela va bien doucement, bien timidement mais je crois être sur la bonne voie.” Pierre Bonnard, Le Grand-Lemps, to Edouard Vuillard, September 19, 1892, in Antoine Terrasse, ed., Bonnard/Vuillard correspondance (Paris: Gallimard, 2001), 23.

-

Examples of this palette in his graphic work can be found in the Nelson-Atkins collection. See, for example, La Revue blanche, 1894, lithograph in four colors on off-white wove paper, framed: 34 1/8 x 26 3/4 x 3/4 in. (86.7 x 67.9 x 1.9 cm), Bequest of Donald D. Jones, 2001.3.168, https://art.nelson-atkins.org/objects/32282/la-revue-blanch; and Street at Night: Rain, 1899, color lithograph, image: 10 1/16 x 13 7/8 in. (25.6 x 35.2 cm), sheet: 16 x 21 in. (40.6 x 53.3 cm), Purchase: acquired through the generosity of an anonymous donor, F78-3/3, https://art.nelson-atkins.org/objects/7673/street-at-night–rain.

-

While glimpses of charcoal are visible beneath and between paint strokes in certain areas of the composition, infrared reflectography at 1950 nanometers was unable to provide a fuller view of the underlying charcoal sketch. See accompanying technical entry by Mary Schafer and John Twilley, specifically paragraph 1 and figure 10.

-

Schafer and Twilley, technical entry.

-

Schafer and Twilley, technical entry.

-

“Bonnard aime à reprendre ses anciens tableaux. Au musée de Grenoble puis au Luxembourg, il lui arriva de guetter le passage d’un gardien d’une salle à l’autre, de sortir d’une poche une minuscule boîte garnie de deux ou trois tubes et d’un bout de pinceau, ‘d’améliorer’ furtivement de quelques touches.” George Besson, “Lettre à Pierre Betz,” in “Bonnard,” special issue, Le Point: Revue artistique et littéraire 4, no. 24 (1943): 46, quoted in Antoine Terrasse, Bonnard: The Colour of Daily Life (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000), 126.

-

Dauberville and Dauberville, Bonnard, no. 31, p. 1:107. It is unclear if the collector’s name is Bonis Charancle, Boris Charancle, or Denis Charancle. Further information and a more complete history of ownership is provided in this object’s provenance entry.

-

After immigrating to the United States, he changed his name to Georges Lurcy. Frances Brent, “Visual Moment: The Compelling Odysseys of Looted Art,” Moment Magazine, September 9, 2021, https://momentmag.com/odysseys-of-looted-art-pierre-bonnard.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Schafer and John Twilley, “Pierre Bonnard, Still Life with Guelder Roses, 1892; reworked 1929,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.704.2088.

MLA:

Schafer, Mary and John Twilley. “Pierre Bonnard, Still Life with Guelder Roses, 1892; reworked 1929,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.704.2088.

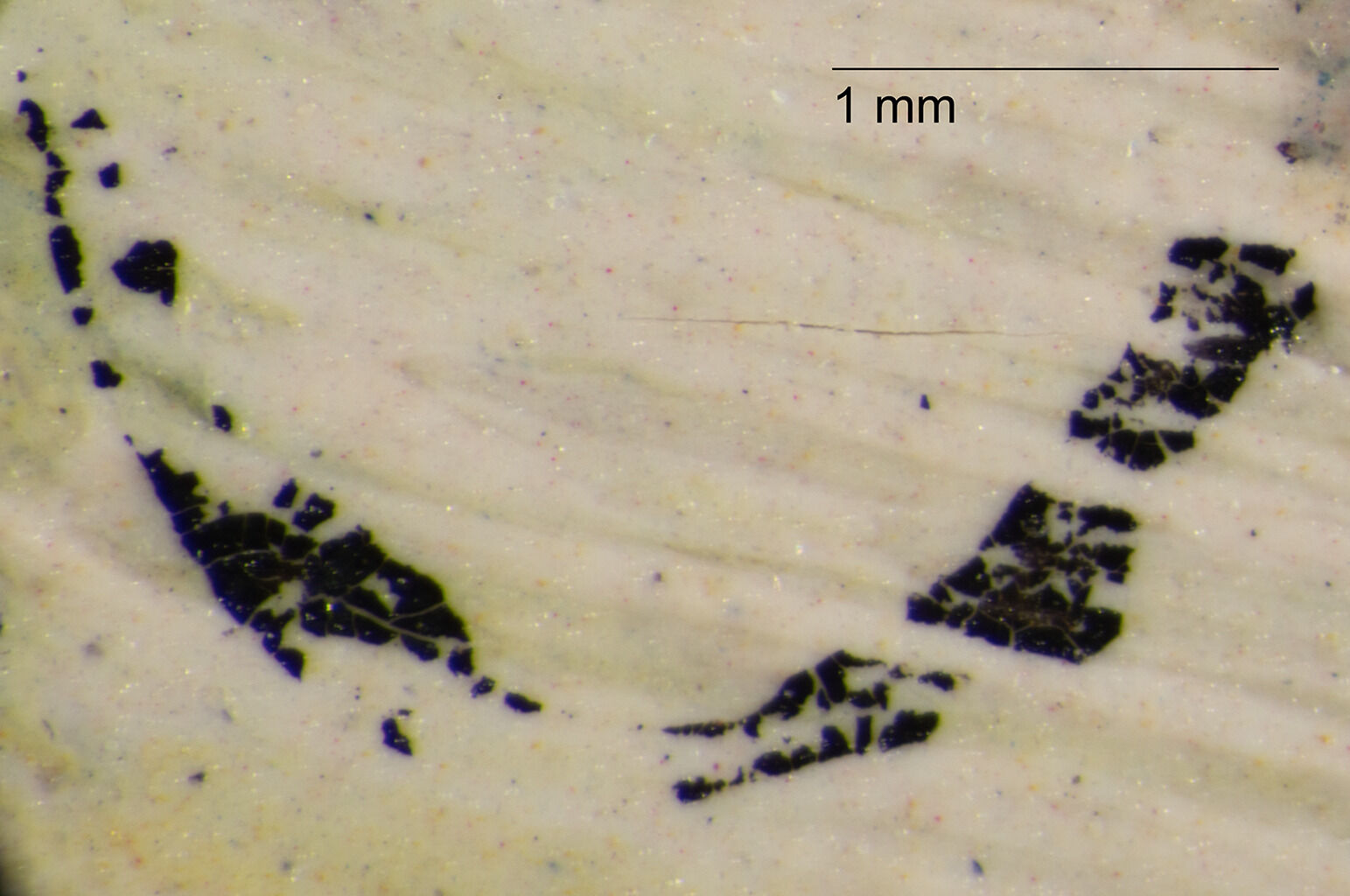

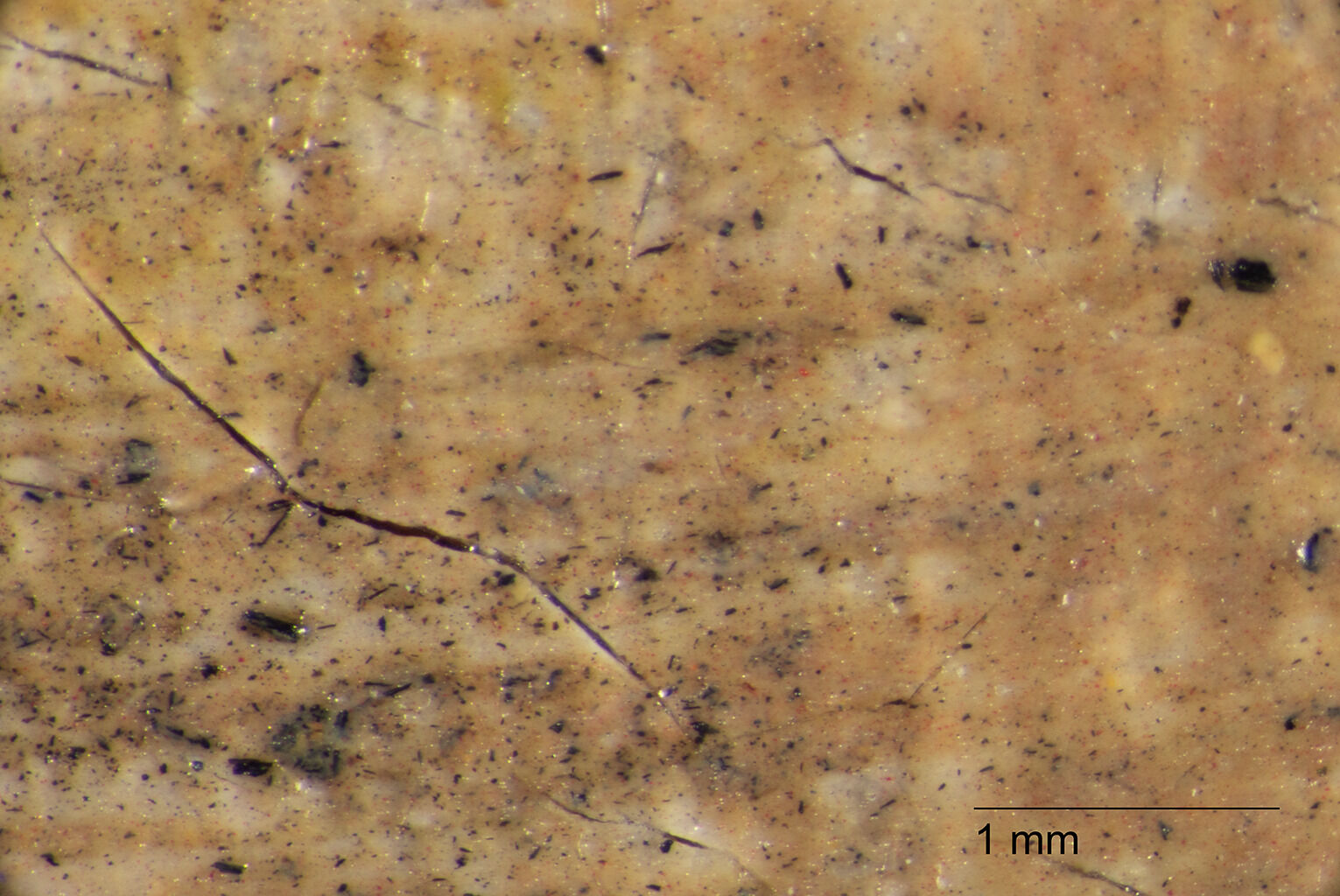

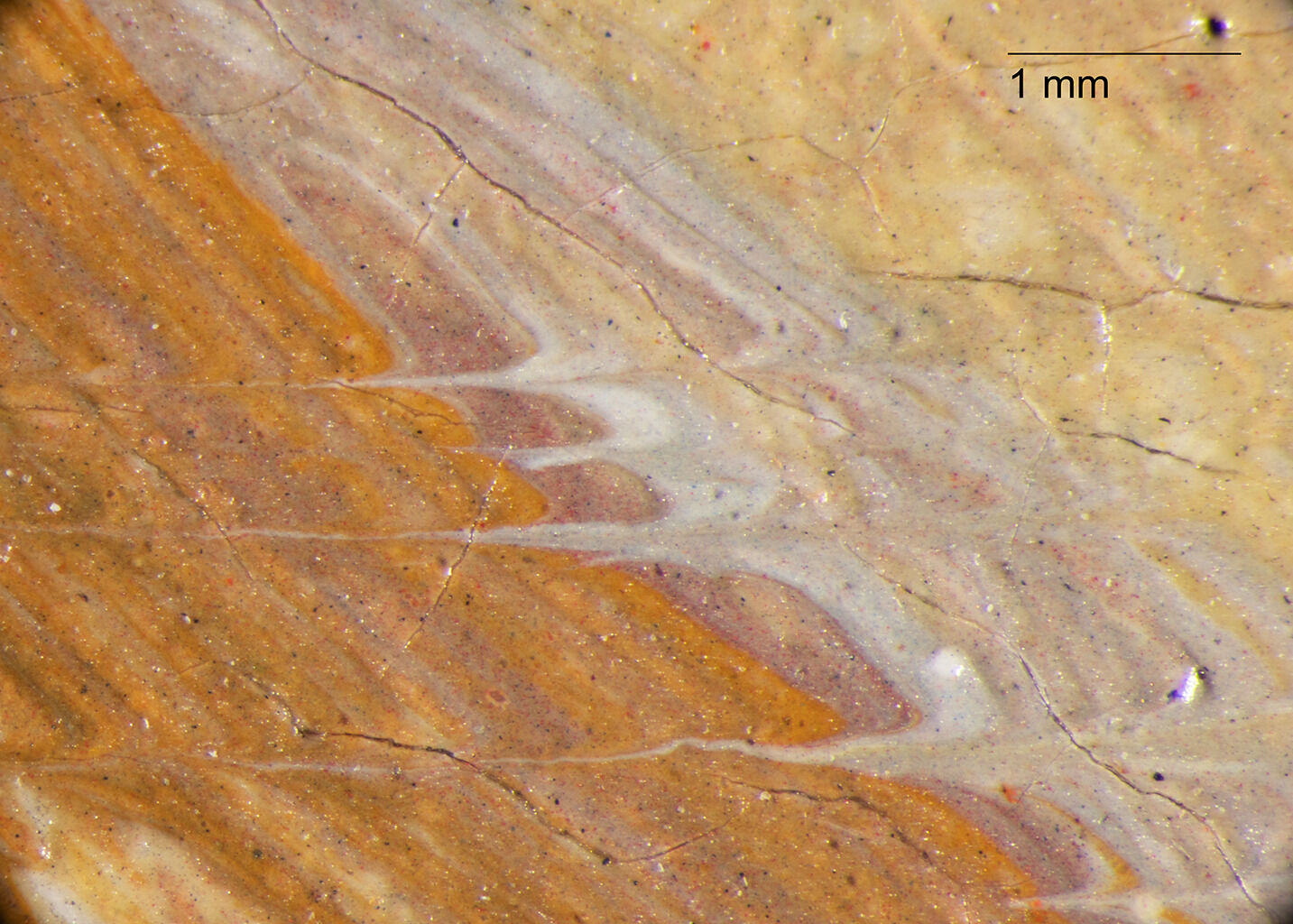

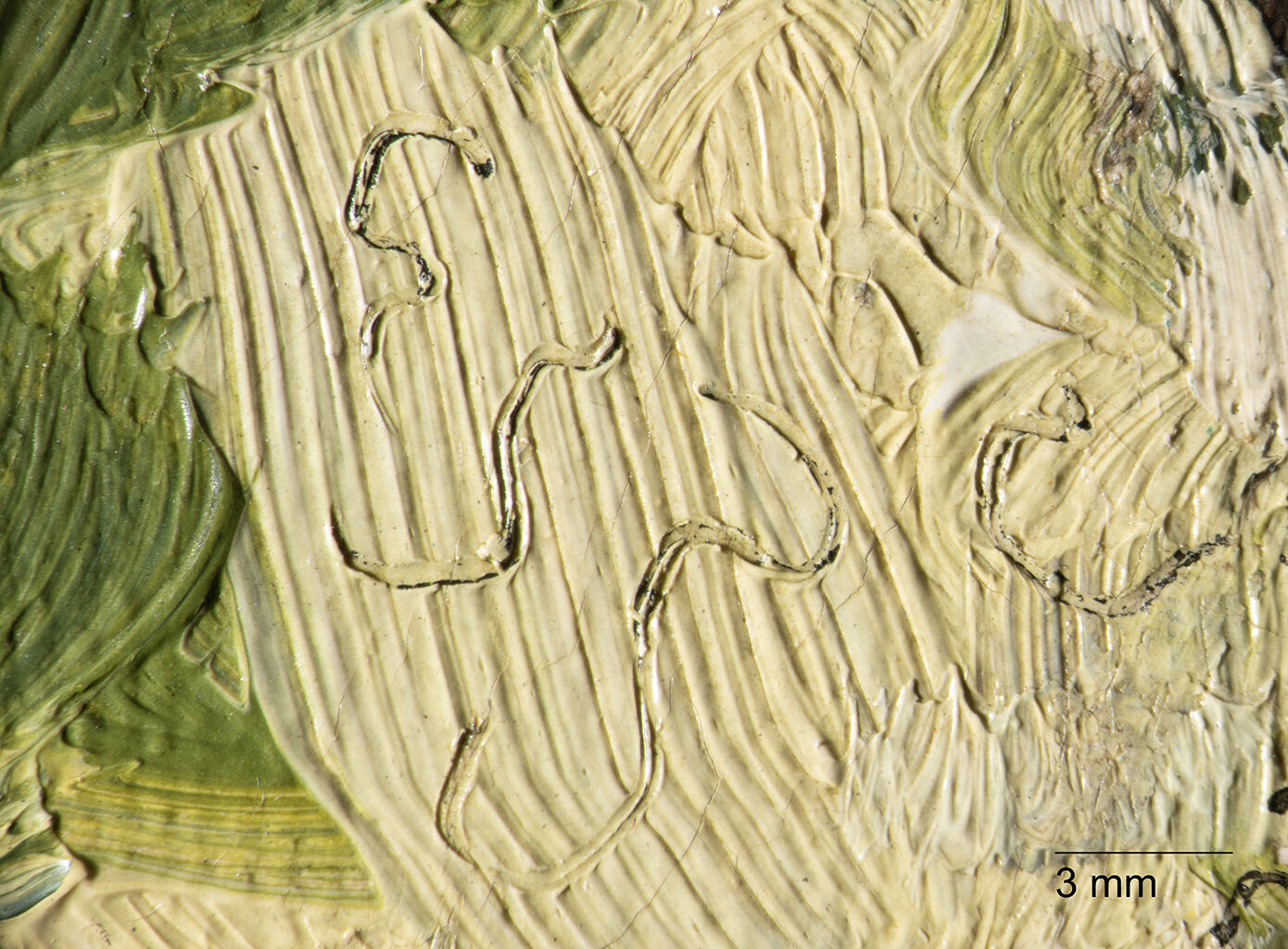

Still Life with Guelder Roses was executed on a plain-weave canvasplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. with a white, commercially applied, lead-based groundground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer..1The elemental composition of the ground layer was confirmed to be lead-based with traces of chloride (not considered original to the ground or paint film), with no barite present. John Twilley, “Analyses Undertaken on Bonnard’s Still Life with Guelder Roses, 2004.12,” unpublished report, February 23, 2025, NAMA conservation file, 2004.12. Over this prepared surface, Pierre Bonnard loosely sketched out the floral motif using charcoal. When the paint surface is studied under the stereomicroscope, splintered particles of charcoal are visible beneath the paint of the cloth (Fig. 6) and along the lower left edge of the vase. A few glimpses of charcoal line are also apparent between the paint strokes of the flowers and greenery (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph of the vase, Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892), revealing charcoal particles dispersed by an overlying stroke of fluid orange paint

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph of the vase, Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892), revealing charcoal particles dispersed by an overlying stroke of fluid orange paint

Fig. 7. Photomicrograph of sketch line visible between paint strokes of the leaves, Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892)

Fig. 7. Photomicrograph of sketch line visible between paint strokes of the leaves, Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892)

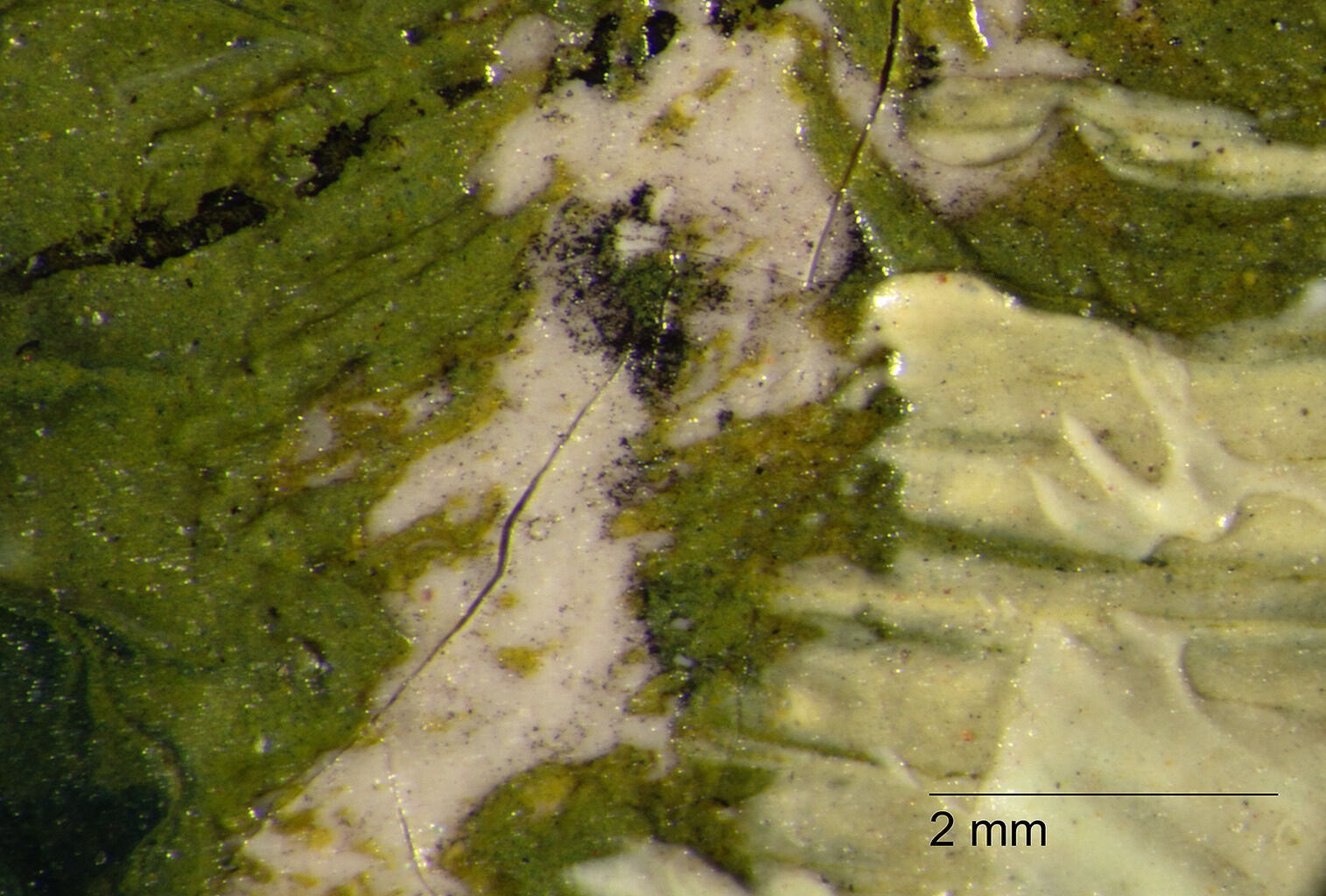

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of the wet-over-wet brushwork between the leaves and background, Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892)

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of the wet-over-wet brushwork between the leaves and background, Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892)

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of wet-into-wet mixing of paint colors, Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892)

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of wet-into-wet mixing of paint colors, Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892)

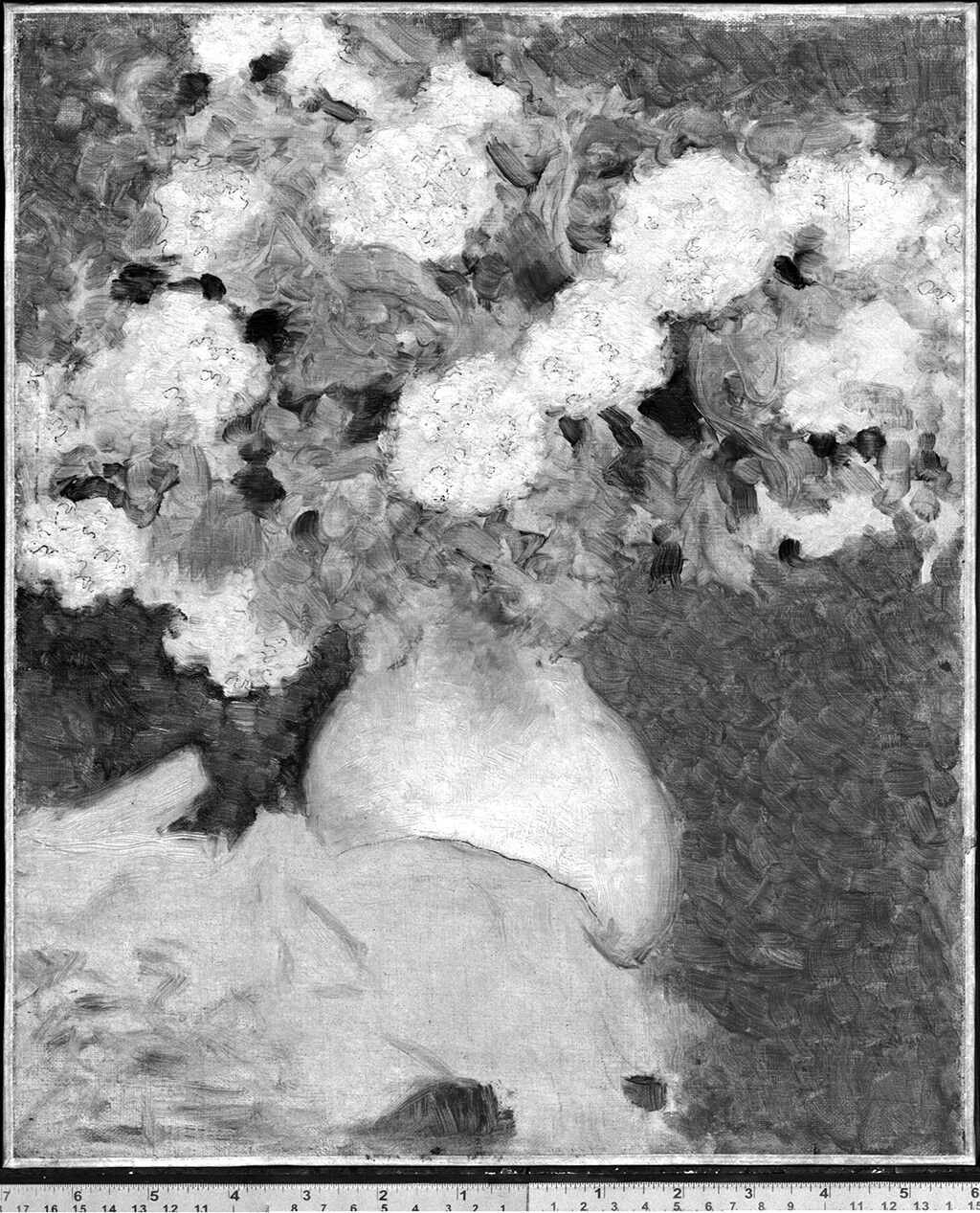

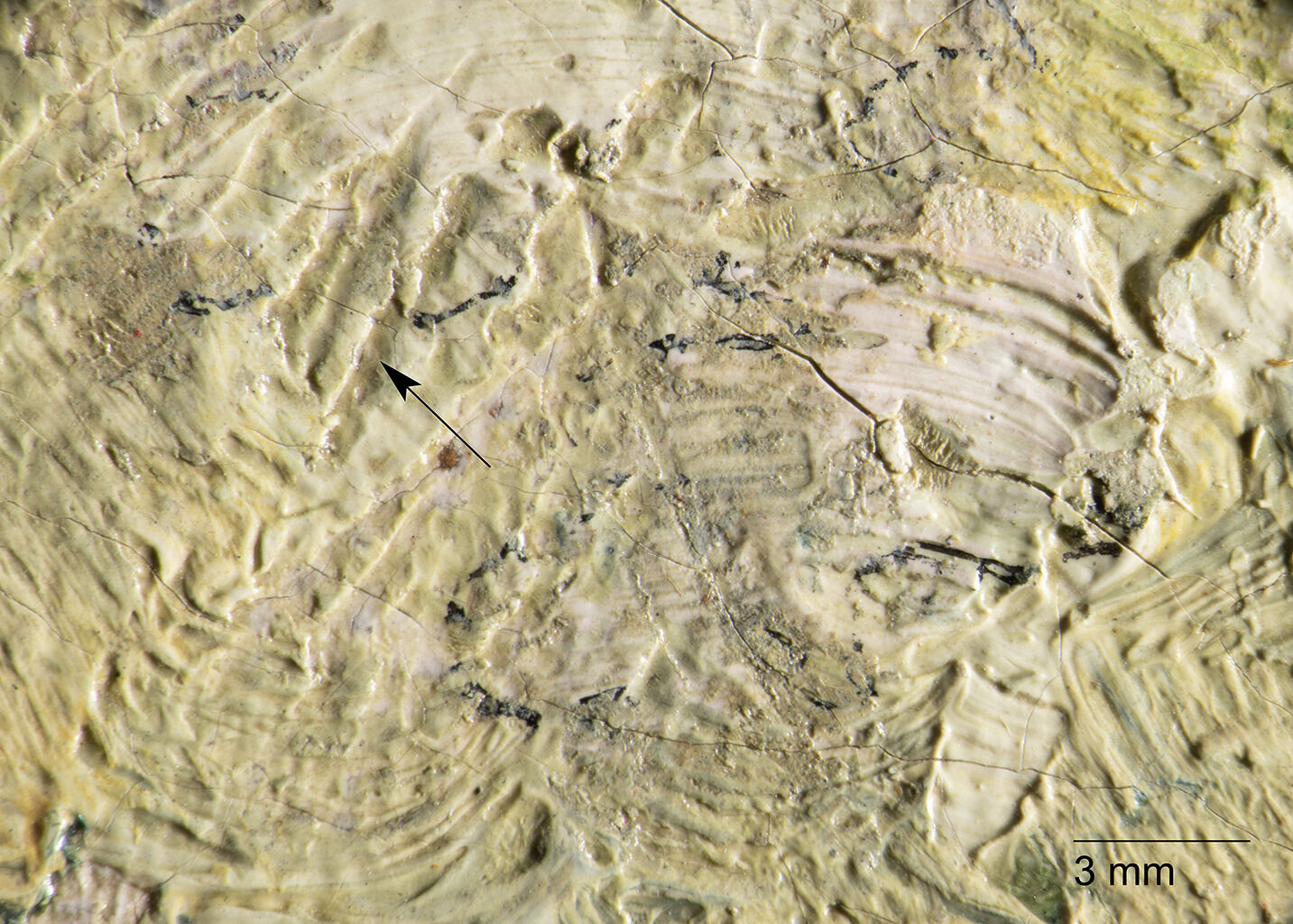

Extensive wet-over-wetwet-over-wet: An oil painting technique which involves drawing a stroke of one color across the wet paint of another color. and wet-into-wetwet-into-wet: An oil painting technique which involves blending of colors on the picture surface. brushwork suggests that the still life was completed over a short period of time and its compositional elements were built up in unison (Figs. 8, 9). The overlapping and intermingling of paint at the borders of leaves, flowers, and background produced a blurring effect at the edges of forms. With a flat 1/4-inch paintbrush, Bonnard defined the blooms and greenery with painterly strokes, while the gray-brown background was constructed using a series of short diagonal and horizontal paint strokes in the lower right and center-left, respectively. Visually the painting’s background appears flat, but its directional brushwork is readily visible in the infrared reflectograminfrared reflectogram: An infrared image captured with an electronic infrared imager, typically in the 1000-2500 nanometer range. See Infrared reflectography (IRR). of Figure 10.

Fig. 10. Infrared reflectogram captured at 1950 nanometers, Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892)

Fig. 10. Infrared reflectogram captured at 1950 nanometers, Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892)

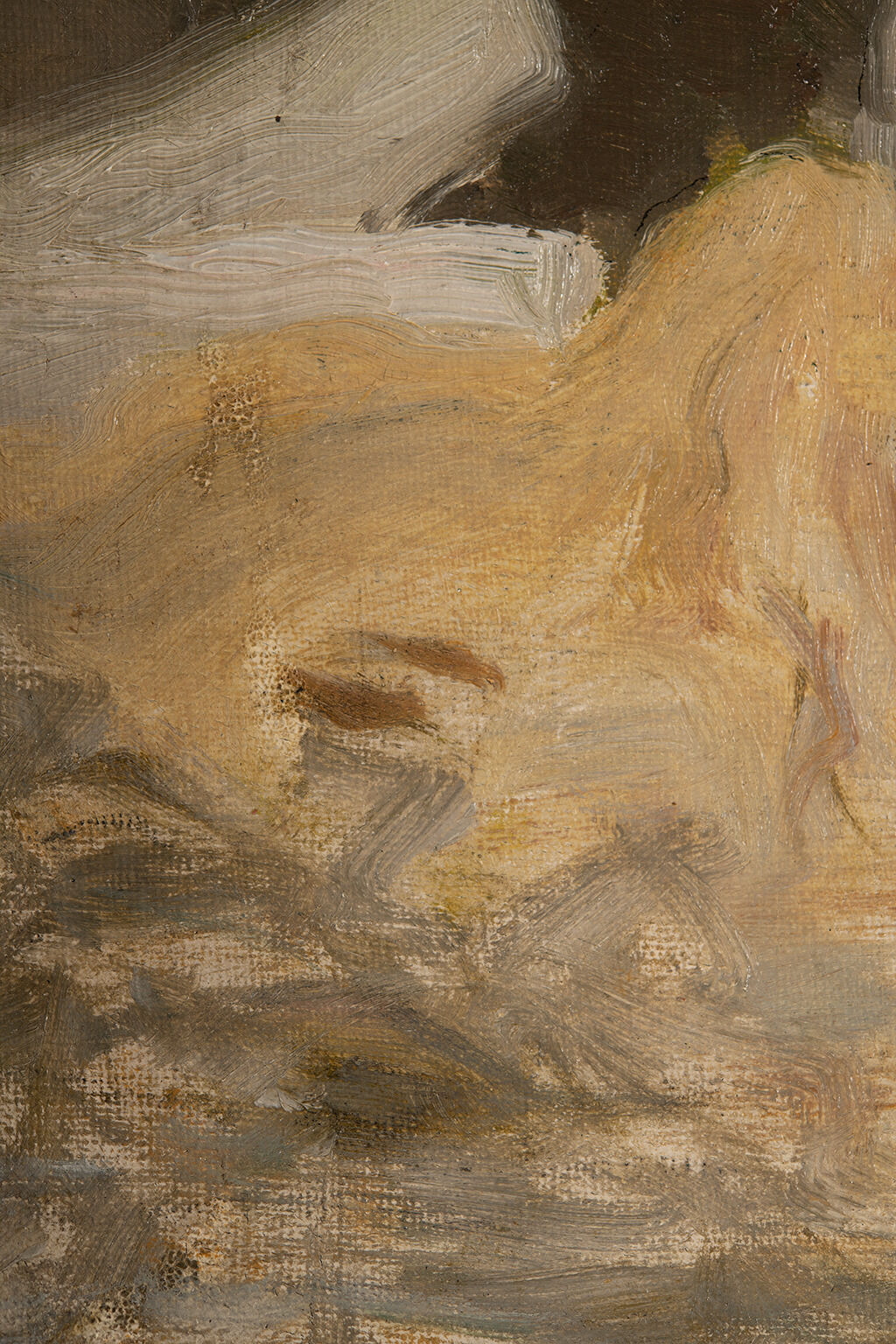

Fig. 11. Detail of the lower left quadrant, Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892)

Fig. 11. Detail of the lower left quadrant, Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892)

In contrast to the rest of the still life, the lower left corner of the painting is sparsely painted with dry brushwork that skips over the surface of the white ground, producing a textural effect (Fig. 11). Cool gray paint strokes and scumblesscumble: A thin layer of opaque or semi-opaque paint that partially covers and modifies the underlying paint. loosely suggest the folds of the yellow-orange cloth, an ambiguous element of the painting that points to the artist’s ruminations on optical blurring in his translation of three-dimensional subjects to paint on canvas.2Bonnard sought to incorporate the “reflexive distortions that come with transforming visual reality into a picture.” See Elizabeth Hutton Turner, Pierre Bonnard: Early and Late (London: Philip Wilson, 2002), 53.

At this early point in his career, Bonnard combined both drawing and painting materials in his process, often incorporating graphite, oil paint, charcoal, and graphic lines drawn with ink and pen. Although charcoal was mainly used for the preliminary sketch, here it is also present in the two dark shapes (shadows?) of the cloth. Charcoal particles on the larger rectangular shape appear to have been covered by subsequent paint, whereas charcoal on the small rectangular shape remained unpainted.

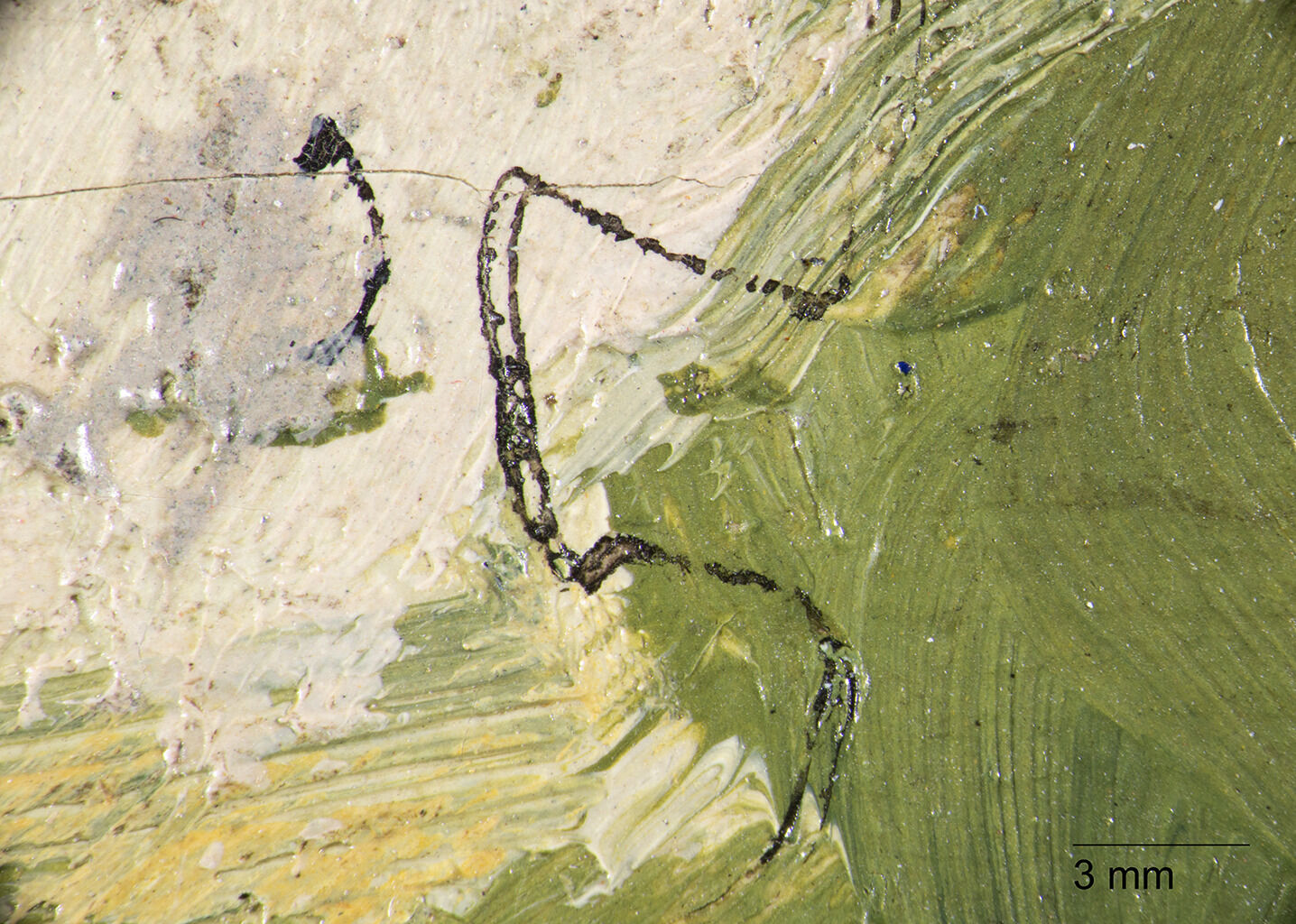

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of the ink drawn onto the painted flowers, Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892), showing the double lines created by the nib of the artist’s pen

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of the ink drawn onto the painted flowers, Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892), showing the double lines created by the nib of the artist’s pen

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph with raking illumination, Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892), showing incised marks made into the wet paint of the flowers

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph with raking illumination, Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892), showing incised marks made into the wet paint of the flowers

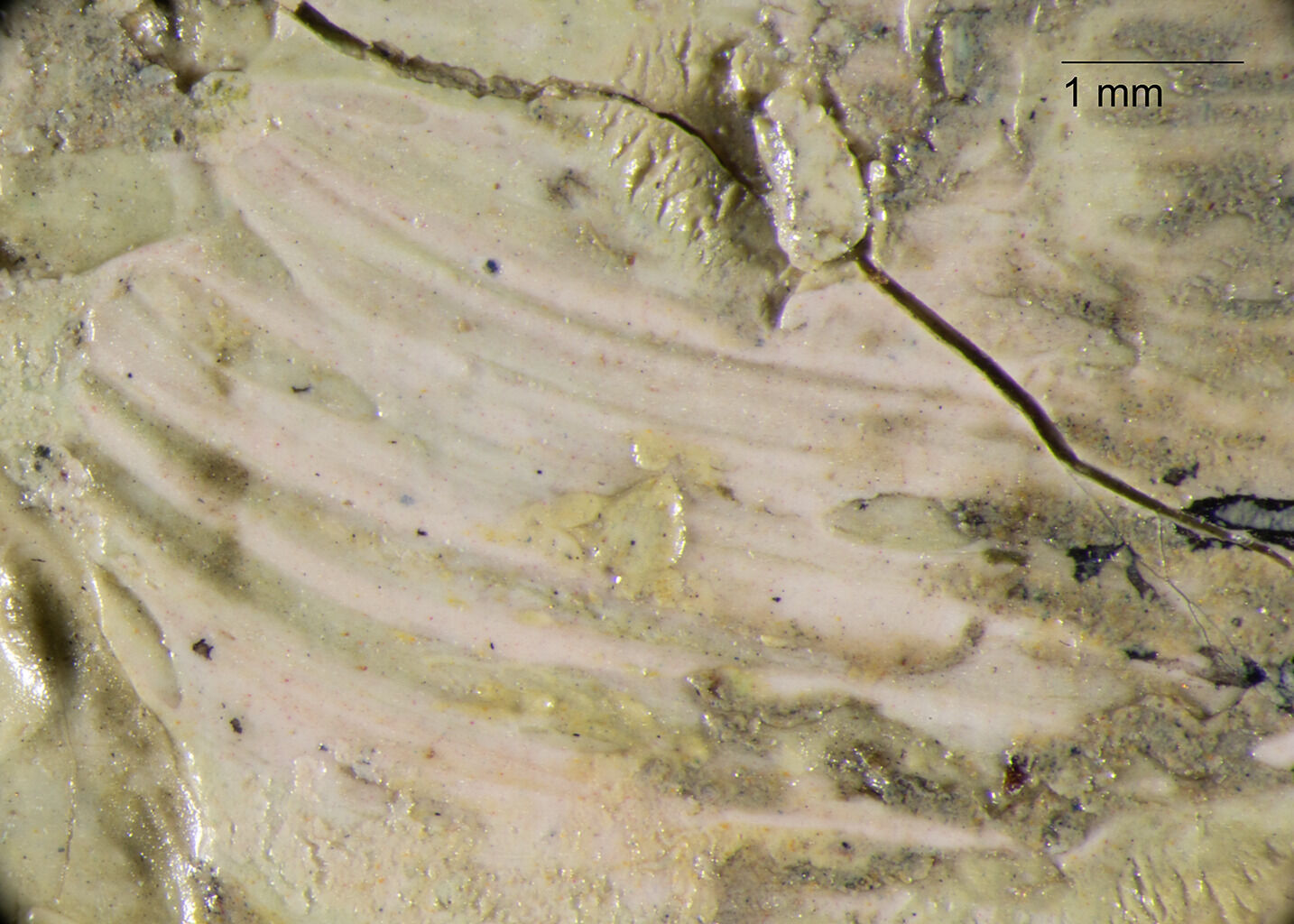

Additionally, Bonnard drew ribbon-like, undulating lines of opaque carbon black ink3Raman spectroscopy confirmed the presence of amorphous carbon black (i.e., not crystalline graphite) in the ink. See Twilley, “Analyses Undertaken on Bonnard’s Still Life with Guelder Roses, 2004.12.” to portray the ruffling petals, outer edges of the flowers, and the contour of the vase. Other paintings produced around this time appear similar in terms of media and technique: Flowers: Snowballs (Fig. 2), Afternoon in the Garden (Fig. 4), and Woman with Dog (1891; Clark Art Institute).4Sandra L. Webber, technical report in Nineteenth-Century Paintings at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, ed. Sarah Lees (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 1:67. In many instances double lines were formed by the pen nib, as the tool splayed in response to the pressure applied (Fig. 12). Most ink lines were drawn across fully dry paint, skipping across the underlying paint textures, although there are a few instances in which the pen incised into still-wet paint (Fig. 13). Many of the ink lines are now partially covered by paint that the artist added years later (see discussion of reworking below).

Bonnard described himself as painting “with a brush in one hand, a rag in the other,” notes scholar Bernard Dunstan. “He would take out paint by wiping and rubbing as well as with a knife, as this could give him a more suggestive, clouded surface to paint into.”5Bernard Dunstan, Painting Methods of the Impressionists, (New York: Watson-Guptill, 1983), 144–45. Indeed there are areas on the Nelson-Atkins painting where he scraped and incised into the partially dry paint of the blooms with a sharp tool (Fig. 14). Similar scraping of the paint surface has been documented on Bonnard’s Nude (1903; Gothenberg Museum of Art, WL84).6Victoria Skalleberg, “Nude (Aprés le Bain): An Inter-Disciplinary Technical Study of an Oil Painting on Cardboard by Pierre Bonnard” (master’s thesis, Department of Conservation, University of Gothenburg, 2020), 37, fig. 19.

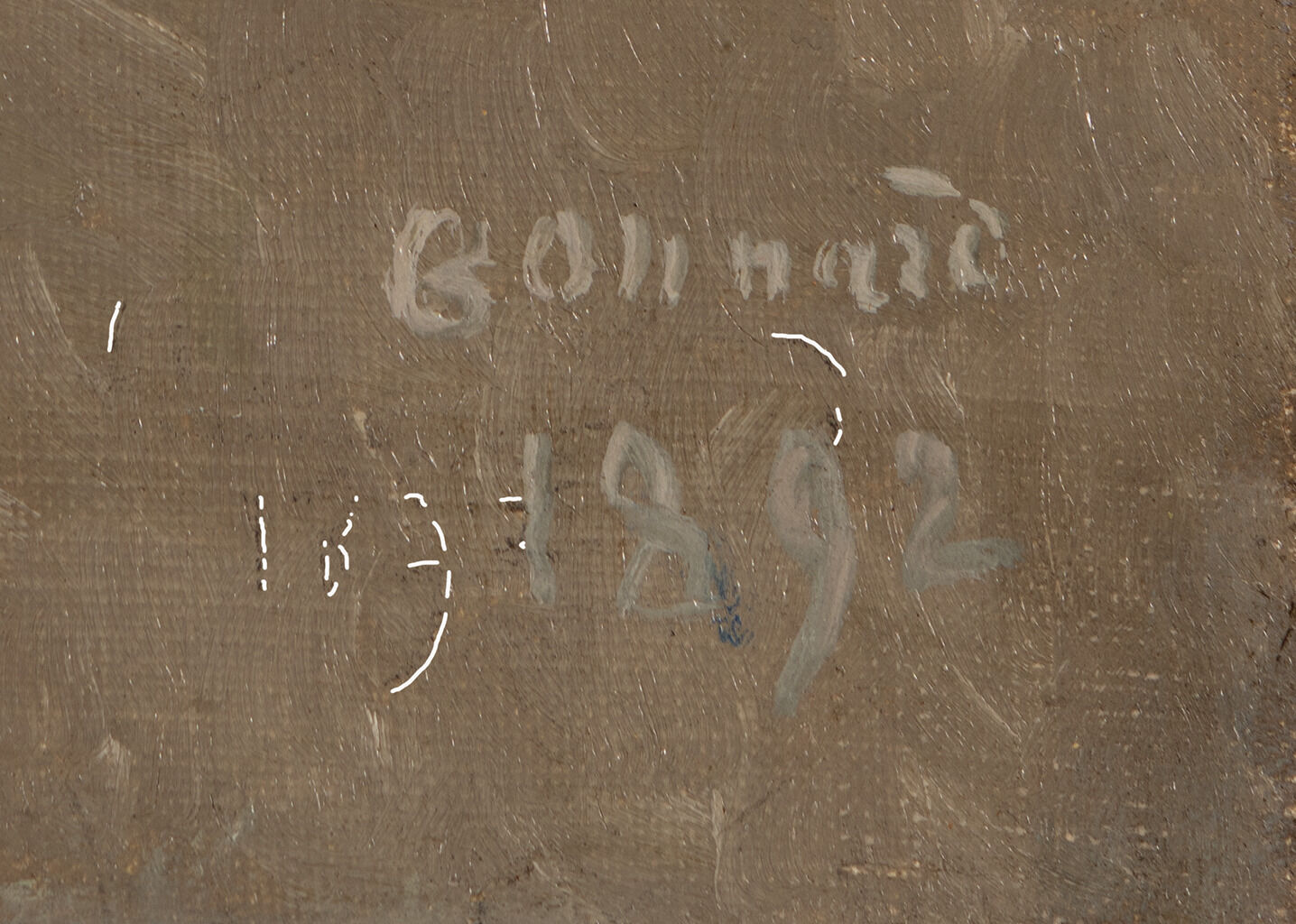

There are many anecdotes about Bonnard’s tendency to modify his paintings years later,7Skalleberg, “Nude (Aprés le Bain),” 55. See also Margrit Hahnloser-Ingold, “‘Promenade en mer’—Image and Portrait,” in Bonnard: The Late Paintings, exh. cat., ed. Sasha M. Newman (London: Thames and Hudson, 1984), 82; Sarah Whitfield, “Fragments of an Identical World,” in Whitfield and John Elderfield, Bonnard, exh. cat. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998), 26, 31n123. and according to the 1965 catalogue raisonné by Jean and Henry Dauberville, Bonnard reworked and re-signed the Nelson-Atkins painting in 1929.8Jean Dauberville and Henry Dauberville, Bonnard: Catalogue raisonńe de l’oeuvre peint (Paris: Éditions J. et H. Bernheim-Jeune, 1965), 1:107. The Nelson-Atkins painting is listed as “retouché et signé par Bonnard en 1929” (retouched and signed by Bonnard in 1929). In this case, the artist appears to have reworked the blooms, using wet-over-drywet-over-dry: An oil painting technique that involves layering paint over an already dried layer, resulting in no intermixing of paint or disruption to the lower paint strokes. touches of gray-green, gray-lavender, and yellow-green paint to partially cover the ink lines (Fig. 15).9Flowers: Snowballs was also listed in the Dauberville catalogue as having been reworked in 1929, although in this case, the artist’s additions do not appear to have disrupted the ink lines. See Dauberville and Dauberville, Bonnard, 1:106. See also Fig. 2 in this catalogue entry. These later additions are made up of coarse pigments that produce a grittier texture when compared to the underlying paint. The paint was applied in dabs but also appears to have been rubbed or scraped across the existing paint. Loss of ink is also present in many areas (Fig. 16), but it is unclear if this is due to the artist’s scraping or past treatment. An orange paint stroke partially covers an ink line at the boundary of the fabric and vase; this paint also covers cracks, indicating that it was added later. The overall impact of the 1929 reworking is a dampening effect of the flat, graphic ink lines and a shift away from his early decorative painting style.

On the lower right, Bonnard signed and dated the painting—“Bonnard 1892”—with light gray paint. Given that the wet-over-dry brushwork caused no disruption to the underlying textures of the background paint (Fig. 17), it is possible that this inscription was added in 1929. Furthermore, traces of dark material raise the possibility of an earlier signature in this same location. Figure 18 reveals the faint “189” as well as an arcing shape that echoes the upward curve of Bonnard’s “d.” This potential modification to the signature does not seem unusual for the artist. A 2020 technical study of Nude revealed a faint date on the top edge, and based on archival photographs and ultravioletultraviolet (UV) radiation: A segment of the electromagnetic spectrum, just beyond the sensitivity of the human eye, with wavelengths ranging from 100–400 nanometers. For a description of its use in the study of art objects, see ultraviolet (UV) fluorescence or UV-induced visible fluorescence. examination, Bonnard appears to have made some minor adjustments to the Gothenberg painting sometime after 1923, which included covering the date with paint.10Skalleberg, “Nude (Aprés le Bain),” 41–42, 59, figs. 31–32.

Fig. 18. Detail of the lower right of Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892), showing traces of brown material which may be associated with an earlier signature

Fig. 18. Detail of the lower right of Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892), showing traces of brown material which may be associated with an earlier signature

Fig. 19. Photomicrograph of a bloom, Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892), revealing a white dab of paint with a subtle pink color

Fig. 19. Photomicrograph of a bloom, Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892), revealing a white dab of paint with a subtle pink color

Fig. 20. Photomicrograph of a leaf on the center right, Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892)

Fig. 20. Photomicrograph of a leaf on the center right, Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892)

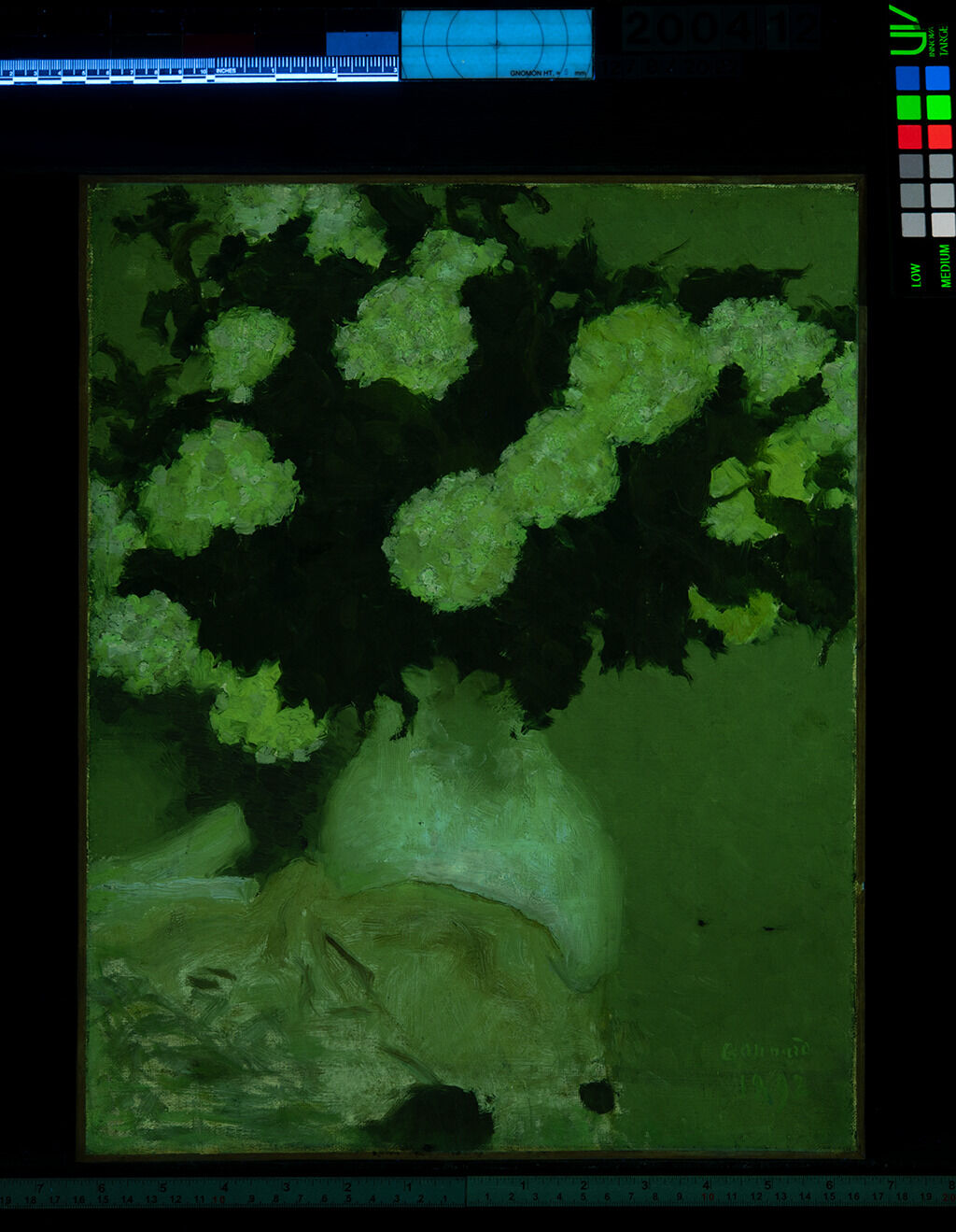

Fig. 21. Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence photograph of Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892)

Fig. 21. Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence photograph of Still Life with Guelder Roses (1892)

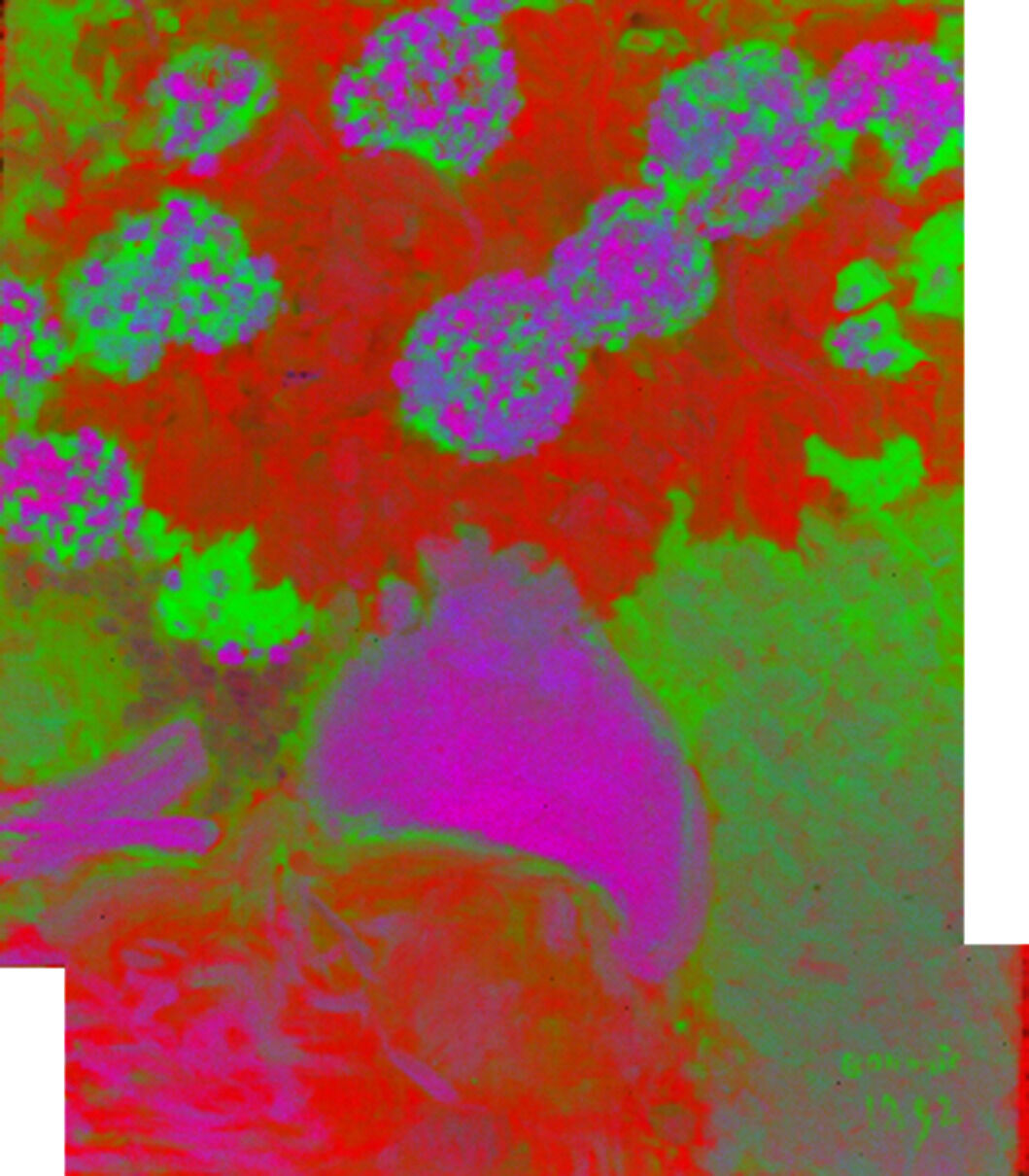

Some of the white paint strokes on the flowers exhibit a faint pink tinge, and the paint mixture of a green leaf on the center right includes pink (Figs. 19, 20). Moreover, the lower center of the vase produces a slight pink UV-induced visible fluorescenceultraviolet (UV) fluorescence or UV-induced visible fluorescence: The reflected visible light produced when painting materials interact with ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Not all materials fluoresce, but the color and intensity of the fluorescence is frequently used to differentiate between original and restoration materials, characterize the varnish layers, or reveal the distribution of pigments across the composition. (Fig. 21), which could signal the use of red lake.11Danielle Measday, Charlotte Walker, and Briony Pemberton, “A Summary of Ultra-violet Fluorescent Materials Relevant to Conservation,” Australian Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Material National Newsletter, no. 137 (March 2017): https://aiccm.org.au/network-news/summary-ultra-violet-fluorescent-materials-relevant-conservation/. Late in his career, Bonnard’s palette included a range of carmine and madder lakes,12Dunstan, Painting Methods of the Impressionists, 145. although there are few pigment studies available for his earlier paintings. Like the Nelson-Atkins still life, analysis of Nude revealed the use of vermilion in the pink flesh tones, but its absence in purple areas raised the possibility of an organic pigment.13See Skalleberg, “Nude (Aprés le Bain),” 49.

Technical analysis of Still Life with Guelder Roses was undertaken to explore whether lake pigments may have impacted the original colors of the still life. A limited number of samples were studied by scanning electron microscopy (SEM)scanning electron microscopy (SEM): Performed on a microsample of paint, the SEM provides a means of studying particle shapes beyond the magnification limits of the light microscope. This becomes increasingly important with the painting materials introduced in the early modern era, which are finer and more diverse than traditional artists’ materials. The SEM is routinely used in conjunction with an X-ray spectrometer, so that elemental identifications can be made selectively on the same minute scale as the electron beam producing the images. SEM methods are particularly valuable in studying unstable pigments, adverse interactions between incompatible pigments, and interactions between pigments and surrounding paint medium, all of which can have profound effects on the appearance of a painting. and polarized light microscopy (PLM)polarized light microscopy (PLM): A method used for the study and differentiation of pigments based on the optical properties of individual particles, including color, refractive index, birefringence, etc. PLM is particularly useful in identifying the presence of organic pigments such as indigo and Prussian blue, which often cannot be differentiated from paint medium in the scanning electron microscopy (SEM); differentiating synthetic pigments from their natural analogs by particle shape or the presence of extraneous mineral matter; and disclosing the presence of pigments with similar composition but differing color, such as red and yellow iron oxides., and a partial understanding of Bonnard’s palette was obtained with X-ray fluorescence spectrometry elemental mapping (MA-XRF)X-ray fluorescence spectrometry elemental mapping (MA-XRF) or XRF elemental mapping: A non-destructive technique that entails collecting thousands of X-ray fluorescence spectra at regular intervals across a painting to build an alternate set of images depicting the locations and amounts of different elements. Although the information is fundamentally the same as measurements gathered from a single-point XRF, the graphical nature of the result is often a more powerful technique for understanding trends in an artist’s use of materials. The high number of spectra allows statistical manipulations of the elemental information to locate correlations between different pigments that would not be possible from a small number of tests. For example, the consistent occurrence of mercury along with chromium, and iron along with copper, could show that vermilion was used to mute the chrome green and red ocher was similarly employed in a mixture that includes emerald green. The resulting correlation maps then serve to show where the two cases occur in the composition. MA-XRF can also reveal preliminary paint applications that became covered as the composition was completed, thereby disclosing aspects of the painter’s method..14It is important to note that ultramarine and Prussian blue, if not used in concentrated form, could be present on the painting but lack distinctive elemental responses for MA-XRF detection. A sample obtained from a white bloom contains lead white, zinc white, and low levels of the following: chromium (likely indicative of viridian), one of the copper acetoarsenite greens, vermilion, lead chromate yellow, and trace levels of fillers, including crushed natural barite, potassium clay, and quartz.

Some of the complexity in the MA-XRF elemental maps relates to the various roles of elements such as barium, which is most concentrated in the blooms, vase, and lower left quadrant. Barium certainly serves here as a colorless extender but could also function as a base for a lake pigment. Sulphur only partially correlates with barium, which indicates another origin. Levels of vermilion (HgS) are too low to contribute to the sulfur map in any meaningful way, as it is present mainly in the red-brown shadows at the center left, neck of the vase, and in the flowers and leaves (trace amounts). The sulfur distribution is tied most closely to the distribution of potassium, where it could occur in a residual alum lake. Potassium is present in abundance throughout the green foliage, individual flower petals, vase, and, to a lesser degree, the background and fabric. Figure 22 illustrates the varying distributions between mercury, sulfur, and potassium across the painting. However, none of the samples confirm a lake pigment, and so additional sampling, SEM-based study, and perhaps other analytical techniques are necessary to produce more definitive answers.

Even though ultramarine and Prussian blue cannot be detected with MA-XRF, there are other pigments that can be extrapolated from this analytical technique. Lead white and zinc white often occur in the same areas, but their usage is inversely related, meaning that if one is elevated, the other is reduced (Fig. 23). Lead white is present in the vase, green leaves, and whitest paint of the flower petals, while zinc white contributes to the background and other parts of the flowers, including the gray paint that is estimated to be later additions made by the artist.

Although copper acetoarsenite green is found in the flower stems, chromium is the greatest contributor to the greenery, probably in the form of viridian, and is also present in the flowers as chrome yellow.15SEM revealed that traces of viridian were identified in the flowers. Copper acetoarsenite green and iron earths (implied by the correlation of iron and silicon) are also present in the leaves and stems. Low levels of cobalt, likely as cobalt blue, match the cool gray paint on the cloth and a paint stroke at the border between the vase and cloth, and it is a major component of the current signature. Cadmium is present in the leaves, where yellow cadmium sulfide may be a component in the greens and in yellow parts of the flowers and fabric. It also occurs in the white vase, although this element was not detected in the pale yellow analyzed with SEM.

The canvas is glue-linedlining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive., the stretcherstretcher: A wooden structure to which the painting’s canvas is attached. Unlike strainers, stretchers can be expanded slightly at the joints to improve canvas tension and avoid sagging due to humidity changes or aging. has been replaced, and the tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. have been removed. However, the painted picture planepicture plane: The two-dimensional surface where the artist applies paint. appears to stop short of the top, left, and right edges, and the current dimensions of the still life are close in size to a standard-formatstandard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format. no. 6 figure canvas.16See the Bourgeois Ainé catalogue of 1888 in David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1990), 46. Although Bonnard is known to have affixed unstretched canvas to a rigid board or his studio wall prior to painting, there are no vacant tack holes at the corners of the Nelson-Atkins painting. His preference for a more rigid painting surface began to increase around 1905.17See Christel Hollevoet, “Unstretched/Stretched: Bonnard’s Work Process Reconsidered,” MoMA 1, no. 2 (May 1998): 5.

The still life is in good condition, with scattered paint losses, loss of ink, and paint abrasionabrasion: A loss of surface material due to rubbing, scraping, frequent touching, or inexpert solvent cleaning.. A vertical crack on the upper right, approximately 3 centimeters long, corresponds to the inner edge of a former stretcher member. A subtle diagonal deformation, roughly 13 centimeters long, is present on the lower right quadrant. There is a small amount of flattened impastoimpasto: A thick application of paint, often creating texture such as peaks and ridges. among the flowers resulting from the lining technique. The synthetic varnish, applied in 1976,18Forrest Bailey, treatment report, June 16, 1976, NAMA conservation file, 2004.12. is likely discolored, and it is possible that Bonnard would have preferred an unvarnished surface.19Anthea Callen, “The The Unvarnished Truth: Mattness, ‘Primitivism,’ and Modernity in French Painting, c. 1870–1907,” Burlington 136, no. 1100 (November 1994): 738n3., 20An inscription on the verso of The Backroom Mirror (1908; Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow)—“n’est pas de vernis—P. B.” (do not varnish—P.B.)—indicates that, sixteen years later, Bonnard favored a matte, unvarnished surface. See Andrea Kirsch and Rustin S. Levenson, Seeing Through Paintings: Physical Examination in Art Historical Studies (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 227, fig. 246. There is a small amount of finely painted retouchingretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch. scattered throughout.

Notes

-

The elemental composition of the ground layer was confirmed to be lead-based with traces of chloride (not considered original to the ground or paint film), with no barite present. John Twilley, “Analyses Undertaken on Bonnard’s Still Life with Guelder Roses, 2004.12,” unpublished report, February 23, 2025, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 2004.12.

-

Bonnard sought to incorporate the “reflexive distortions that come with transforming visual reality into a picture.” See Elizabeth Hutton Turner, Pierre Bonnard: Early and Late (London: Philip Wilson, 2002), 53.

-

Raman spectroscopy confirmed the presence of amorphous carbon black (i.e., not crystalline graphite) in the ink. See Twilley, “Analyses Undertaken on Bonnard’s Still Life with Guelder Roses, 2004.12.”

-

Sandra L. Webber, technical report in Nineteenth-Century Paintings at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, ed. Sarah Lees (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), 1:67.

-

Bernard Dunstan, Painting Methods of the Impressionists (New York: Watson-Guptill, 1983), 144–45.

-

Victoria Skalleberg, “Nude (Aprés le Bain): An Inter-Disciplinary Technical Study of an Oil Painting on Cardboard by Pierre Bonnard” (master’s thesis, Department of Conservation, University of Gothenburg, 2020), 37, fig. 19.

-

Skalleberg, “Nude (Aprés le Bain),” 55. See also Margrit Hahnloser-Ingold, “‘Promenade en mer’—Image and Portrait,” in Bonnard: The Late Paintings, exh. cat., ed. Sasha M. Newman (London: Thames and Hudson, 1984), 82; Sarah Whitfield, “Fragments of an Identical World,” in Whitfield and John Elderfield, Bonnard, exh. cat. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998), 26, 31n123.

-

Jean Dauberville and Henry Dauberville, Bonnard: Catalogue raisonńe de l’oeuvre peint (Paris: Éditions J. et H. Bernheim-Jeune, 1965), 1:107. The Nelson-Atkins painting is listed as “retouché et signé par Bonnard en 1929” (retouched and signed by Bonnard in 1929).

-

Flowers: Snowballs was also listed in the Dauberville catalogue as having been reworked in 1929, although in this case, the artist’s additions do not appear to have disrupted the ink lines. See Dauberville and Dauberville, Bonnard, 1:106. See also Fig. 2 in this catalogue entry.

-

Skalleberg, “Nude (Aprés le Bain),” 41–42, 59, figs. 31–32.

-

Danielle Measday, Charlotte Walker, and Briony Pemberton, “A Summary of Ultra-violet Fluorescent Materials Relevant to Conservation,” Australian Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Material National Newsletter, no. 137 (March 2017): https://aiccm.org.au/network-news/summary-ultra-violet-fluorescent-materials-relevant-conservation/.

-

Dunstan, Painting Methods of the Impressionists, 145.

-

See Skalleberg, “Nude (Aprés le Bain),” 49.

-

It is important to note that ultramarine and Prussian blue, if not used in concentrated form, could be present on the painting but lack distinctive elemental responses for MA-XRF detection.

-

SEM revealed that traces of viridian were identified in the flowers.

-

See the Bourgeois Ainé catalogue of 1888 in David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1990), 46.

-

See Christel Hollevoet, “Unstretched/Stretched: Bonnard’s Work Process Reconsidered,” MoMA 1, no. 2 (May 1998): 5.

-

Forrest Bailey, treatment report, June 16, 1976, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 2004.12.

-

Anthea Callen, “The The Unvarnished Truth: Mattness, ‘Primitivism,’ and Modernity in French Painting, c. 1870–1907,” Burlington 136, no. 1100 (November 1994): 738n3.

-

An inscription on the verso of The Backroom Mirror (1908; Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow)—“n’est pas de vernis—P. B.” (do not varnish—P.B.)—indicates that, sixteen years later, Bonnard favored a matte, unvarnished surface. See Andrea Kirsch and Rustin S. Levenson, Seeing Through Paintings: Physical Examination in Art Historical Studies (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 227, fig. 246.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Pierre Bonnard, Still Life with Guelder Roses, 1892; reworked 1929,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.704.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Pierre Bonnard, Still Life with Guelder Roses, 1892; reworked 1929,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.704.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Pierre Bonnard, Still Life with Guelder Roses, 1892; reworked 1929,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.704.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Pierre Bonnard, Still Life with Guelder Roses, 1892; reworked 1929,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.704.4033.

Given by the artist to Bonis Charancle, Paris [1];

Probably Georges Lurcy (né Léon Georges Levy, 1891–1953), Paris [2];

David David-Weill (1871–1952), Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, inventory no. D.W. 98/33, 1933–September 4, 1943 [3];

Confiscated from David-Weill by German National Socialist (Nazi) forces, by September 4, 1943–May 1945 [4];

Recovered by Allied forces and taken to the Munich Central Collecting Point, May 1945–March 27, 1946 [5];

Returned by Allied forces to France, March 27, 1946;

Restituted by France to David-Weill, by June 1946–July 7, 1952 [6];

Inherited by his wife, Flora (née Raphaël, 1878–1970) David-Weill, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, July 7, 1952–April 3, 1970;

By inheritance to her heirs, April 3, 1970–June 9, 1972 [7];

Purchased from the David-Weill heirs, through Galerie Schmit, Paris, by Herman R. (1913–2006) and Helen (née Delano, 1914–2004) Sutherland, Mission Hills, KS, June 9, 1972–2004;

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2004.

Notes

[1] For constituent, see Jean Dauberville and Henry Dauberville, Bonnard: Catalogue Raisonne de l’Œuvre Peint, 1888–1905 (Paris: Éditions J et H. Bernheim-Jeune, 1965), no. 31, p. 1:107. It is uncertain if the spelling of the collector’s name is Bonis Charancle, Boris Charancle or Denis Charancle.

For “Boris,” see Impressionist and Modern Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture (London: Christie, Manson, and Woods, November 29, 1972), 30. For “Denis,” see Collection D. David-Weill: Dessins et Tableaux, Histoire de Paris et de ses environs . . . Sujets Divers, Dessins, Aquarelles, Gouaches, Peintures des XVIIIe et XIXe siècles; Tableaux Modernes (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, June 9–10, 1971), lot 291.

The collector may have been Paul Marc Joseph Marie Antoine Bonis-Charancle (1884–1929), who was an amateur French artist and exhibited alongside Bonnard at the Société des Artistes Independent in 1905. Bonnard inscribed a painting (Rooftops, ca. 1897; Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, MA https://museums.fivecolleges.edu/detail.php?t=objects&type=ext&id_number=SC+1962.23) with “Bonnard à Paul Bonis,” and this might be the same individual. Another possible candidate is French playwright Marc Bonis-Charancle (1859–1939), who ran in the same circle as Bonnard’s brother-in-law and composer, Claude Terrasse (1867–1923).

[2] When the painting was removed from the salt mines at Alt Aussee and inventoried at the Munich Central Collecting Point on June 26, 1945 (see note 4 below), it was recorded as bearing the following identifying mark, which is no longer extant: Georges Levy [sic] / 42, Bd de Clichy. See Bundesarchiv, Koblenz, Germany, B323/649, MCCP Restitution card file, Munich no. 887.

In 1940, the Lurcys moved from Paris to the United States, where they continued to collect art. Documentation and paperwork regarding their art collection during this period appears to be lost; see correspondence from Aaron Smithers, Special Collections Research and Instruction Librarian, Wilson Special Collections Library, Chapel Hill, NC, to Danielle Hampton Cullen, NAMA, September 9, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

[3] The date of the David-Weill purchase was provided by Nathalie Petitdidier on behalf of Michel David-Weill in an email to MacKenzie Mallon, NAMA, October 22, 2015, NAMA curatorial file.

[4] See Rose Valland, “Recueil des rapports de Rose Valland au directeur des musées nationaux, 1941–1944 (Précédé d’un texte de J. Jaujard sur ‘les activités dans la Résistance de Mlle Valland’),” September 4, 1943, Ministré de la Culture, D.M.F., Archives des Musées Nationaux, Paris, Folder 93, R.32.1.

The painting was inventoried at the Jeu de Paume, Paris, by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg and assigned number D.W. Mod. 38. It was later transferred to the Nazi warehouse in Nikolsburg Castle on November 15, 1943, and subsequently moved to the salt mine at Alt Aussee, Austria, where it was assigned number 772. See Bundesarchiv, Koblenz, Germany, B323/300, Transporte des Einsatzstabes Reichsleiter Rosenberg in Bergungsdepots nach Schloss Kogl, Amstetten/Seisenegg, Nikolsburg, Füssen, Buxheim, Lager Peter/Alt-Aussee: Kisten–Verzeichnesse David Weill. See also Rose Valland, “Recueil des rapports de Rose Valland au directeur des musées nationaux, 1941–1944 (Précédé d’un texte de J. Jaujard sur ‘les activités dans la Résistance de Mlle Valland’),” November 15, 1943, Ministré de la Culture, D.M.F., Archives des Musées Nationaux, Paris, Folder 126, R.32.1.

[5] Following the discovery of the artworks in the Alt Aussee salt mine by Allied forces in May 1945, the painting entered the Munich Central Collecting Point on June 26, 1945, where it was assigned inventory number 887. It was repatriated to France on March 27, 1946. Copies of the ERR and Munich property cards are also available in the NAMA curatorial file.

[6] David-Weill lent the painting to the exhibition, Les chefs-d’oeuvre des collections privées françaises retrouvés en Allemagne par la Commission de Récupération Artistique et les services alliés, held at the Orangerie des Tuileries, June–August 1946.

[7] The painting was offered for sale at Collection D. David-Weill: Dessins et Tableaux, Histoire de Paris et de ses environs . . . Sujets Divers . . . Tableaux Modernes, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, June 9–10, 1971, lot 295, as Fleurs dans un vase, Boules de neige, but it failed to sell. See email from Laurence Mille, Drouot Documentation, to MacKenzie Mallon, August 31, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Pierre Bonnard, Still Life with Guelder Roses, 1892; reworked 1929,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.704.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Pierre Bonnard, Still Life with Guelder Roses, 1892; reworked 1929,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.704.4033.

Pierre Bonnard, Flowers: Snowballs, 1891, oil on canvas, 16 1/8 x 12 5/8 in. (41 x 32 cm), private collection; illustrated in Jean Dauberville and Henry Dauberville, Bonnard: Catalogue Raisonne de l’Œuvre Peint, 1888–1905 (Paris: Éditions J. et H. Bernheim-Jeune, 1965), no. 30, p. 1: 106.

Pierre Bonnard, Flowers, Snowballs, 1892, oil on canvas, 16 1/8 x 13 in. (41 x 33 cm.), private collection; illustrated in Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale (New York: Sotheby’s, June 20, 2013), 27.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Pierre Bonnard, Still Life with Guelder Roses, 1892; reworked 1929,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.704.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Pierre Bonnard, Still Life with Guelder Roses, 1892; reworked 1929,” documentation entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.704.4033.

Possibly Exposition de Tableaux et Dessins: Quelques Maîtres du 18e et du 19e siècle au profit de la Société des Amis du Louvre et de l’Œuvre de l’Enfance malheureuse, Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, 1938, no. 5, as Vase de fleurs.

Les chefs-d’Œuvre des Collections Françaises retrouvés en Allemagne par la Commission de Récupération Artistique et les Services Alliés, Orangerie des Tuileries, Paris, June–August 1946, no. 50, as Les Boules de neige.

Discriminating Thieves: Nazi-Looted Art and Restitution, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, January 26, 2019– January 26, 2020, no cat.

Afterlives: Recovering the Lost Stories of Looted Art, The Jewish Museum, New York, August 20, 2021–January 9, 2022, no. 2, as Still Life with Guelder Roses.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Pierre Bonnard, Still Life with Guelder Roses, 1892; reworked 1929,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.704.4033.

MLA:

Hampton Cullen, Danielle. “Pierre Bonnard, Still Life with Guelder Roses, 1892; reworked 1929,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.704.4033.

Possibly Exposition de Tableaux et Dessins: Quelques Maîtres du 18e et du 19e siècle au profit de la Société des Amis du Louvre et de l’Œuvre de l’Enfance malheureuse, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Durand-Ruel, 1938), unpaginated, as Vase de fleurs.

Les Chefs-d’Œuvre des Collections Françaises retrouvés en Allemagne par la Commission de Récupération Artistique et les Services Alliés, exh. cat. (Paris: Ministère de l’éducation nationale, 1946), 20, as Les Boules de neige.

Jean Dauberville and Henry Dauberville, Bonnard: Catalogue Raisonné de l’Œuvre Peint, 1888–1905 (Paris: Éditions J. et H. Bernheim-Jeune, 1965), no. 31, p. 1:107, (repro.), as Fleurs: Boules de neige.

Collection D. David-Weill: Dessins et Tableaux, Histoire de Paris et de ses environs . . . Sujets Divers, Dessins-Aquarelles-Gouaches-Peintures des XVIIIe et XIXe siècles; Tableaux Modernes (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, June 9–10, 1971), unpaginated, (repro.), as Fleurs dans un vase, Boules de neige.

Jean-Jacques Lévêque, Les Années de la Belle Époque: 1890–1914 (Paris: ACR, 1991), 254, (repro.), as Boules de neige.

Michel Dauberville and Guy-Patrice Dauberville, Bonnard: Catalogue Raisonné de l’Œuvre Peint, Révisé et Augmente, 1888–1905, 2nd rev. ed. (Paris: Éditions Bernheim-Jeune, 1992), p. 1:107, (repro.), as Fleurs: Boules de neige.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 96, (repro.), as Still Life with Guelder Roses.

“Discriminating Thieves: Nazi-Looted Art and Restitution at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art,” artguidemag.com (ca. January 2019): https://www.artguidemag.com/art-news/discriminating-thieves-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art.

“‘Discriminating Thieves: Nazi-Looted Art and Restitution’ opens at Nelson-Atkins,” ArtDaily.org (January 27, 2019): http://artdaily.com/news/110834/-Discriminating-Thieves–Nazi-Looted-Art-and-Restitution–opens-at-Nelson-Atkins#.XFB_Ns17laR.

Luke X. Martin, “Meet The Kansas City Gumshoe Who Uncovers The Stories Of The Nelson-Atkins’ Nazi-Looted Art,” KCUR (March 17, 2020): https://www.kcur.org/show/up-to-date/2019-03-17/meet-the-kansas-city-gumshoe-who-uncovers-the-stories-of-the-nelson-atkins-nazi-looted-art.

Darsie Alexander et al., Afterlives: Recovering the Lost Stories of Looted Art, exh. cat. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2022), 200–01, as Still Life with Guelder Roses.

Jordan Hoffman, “Afterlives: The incredible stories behind recovered Nazi-looted art,” Guardian (August 23, 2021): https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2021/aug/23/nazi-looted-art-stories-jewish-museum-new-york-city-exhibition.

Frances Brent, “Visual Moment: The Compelling Odysseys of Looted Art,” Moment Magazine (September/October 2021): https://momentmag.com/odysseys-of-looted-art-pierre-bonnard/.

Chloe Sarbib, “What happened to all the art that Nazis looted,” Sun Sentinel (September 8, 2021): https://www.sun-sentinel.com/florida-jewish-journal/fl-jj-what-happened-to-nazi-looted-art-20210908-lrx35de6yjgujea66vzjtl7u4e-story.html.

Eli Anapur, “The Jewish Museum Tells the Lost Stories of Nazi Looted Art,” Widewalls (September 25, 2021): https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/jewish-museum-nazi-looted-art.

Jason Farago, “In ‘Afterlives,’ about looted art, why are the victims an afterthought,” New York Times (September 30, 2021): https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/30/arts/design/afterlives-looted-art-jewish-museum.html.

Jason Farago, “The Stories Promised Are Not Told,” New York Times 171, no. 59,198 (October 1, 2021): C12.

Jason Farago, “In ‘Afterlives,’ about looted art, why are the victims an afterthought,” artdaily.org (October 2, 2021): https://artdaily.cc/news/139860/In–Afterlives—about-looted-art–why-are-the-victims-an-afterthought-#.YVsbVLhKhdh.