![]()

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June/September 1889

| Artist | Vincent van Gogh, Dutch, 1853–1890 |

| Title | Olive Trees |

| Object Date | June/September 1889 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Oliviers; Les Oliviers, effet du matin; Olive Orchard |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 28 3/4 x 36 1/4 in. (73.0 x 92.1 cm) |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 32-2 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June/September 1889,” catalogue entry in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.738.5407

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June/September 1889,” catalogue entry. French Paintings, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.738.5407.

Fig. 1. Vincent van Gogh, Olive Grove, July 1889, oil on canvas, 28 1/2 x 35 15/16 in. (72.4 x 91.9 cm), Collection Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, the Netherlands, KM 104.278. Photo by Rik Klein Gotink

Fig. 1. Vincent van Gogh, Olive Grove, July 1889, oil on canvas, 28 1/2 x 35 15/16 in. (72.4 x 91.9 cm), Collection Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, the Netherlands, KM 104.278. Photo by Rik Klein Gotink

Fig. 2. Vincent van Gogh, The Olive Trees, November 1889, oil on canvas, 28 5/8 x 36 in. (72.6 x 91.4 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1998.325.1. The Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg Collection, Gift of Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg, 1998, Bequest of Walter H. Annenberg, 2002

Fig. 2. Vincent van Gogh, The Olive Trees, November 1889, oil on canvas, 28 5/8 x 36 in. (72.6 x 91.4 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1998.325.1. The Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg Collection, Gift of Walter H. and Leonore Annenberg, 1998, Bequest of Walter H. Annenberg, 2002

While at Saint-Rémy, Van Gogh was under the care of Dr. Théophile Peyron, a former naval doctor. For the first month of the artist’s stay, Peyron insisted he remain inside to rest, so Van Gogh looked out his window to the garden and painted the irises, butterflies, and poppies he saw there.8See Vincent van Gogh, Irises, 1889, oil on canvas, 29 1/4 x 37 1/8 in. (74.3 x 94.3 cm), J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; and Vincent van Gogh, Butterflies and Poppies, May–June 1889, oil on canvas, 13 3/4 x 10 in. (35 cm x 25.5 cm), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. For him, budding flowers symbolized the cycle of life; he saw trees, the landscape, caterpillars, and the emergent cicadas as representative of transformation, something he hoped would happen to him while recuperating.9One year before checking himself in at Saint-Rémy, Van Gogh referenced Émile Zola’s La Faute de l’Abbé Mouret, an 1875 novel about a monk who finds solace in an overgrown garden where a young woman nurses him back to health. This sheds light onto his interest in gardens and his belief in their restorative effect. Jennifer Helvey, Irises: Vincent van Gogh in the Garden (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Publications, 2009), 96. Van Gogh longed to paint outside, beyond the confines of the facility’s enclosed courtyard. By the first week of June, Peyron lifted the restrictions, and Van Gogh got his wish.

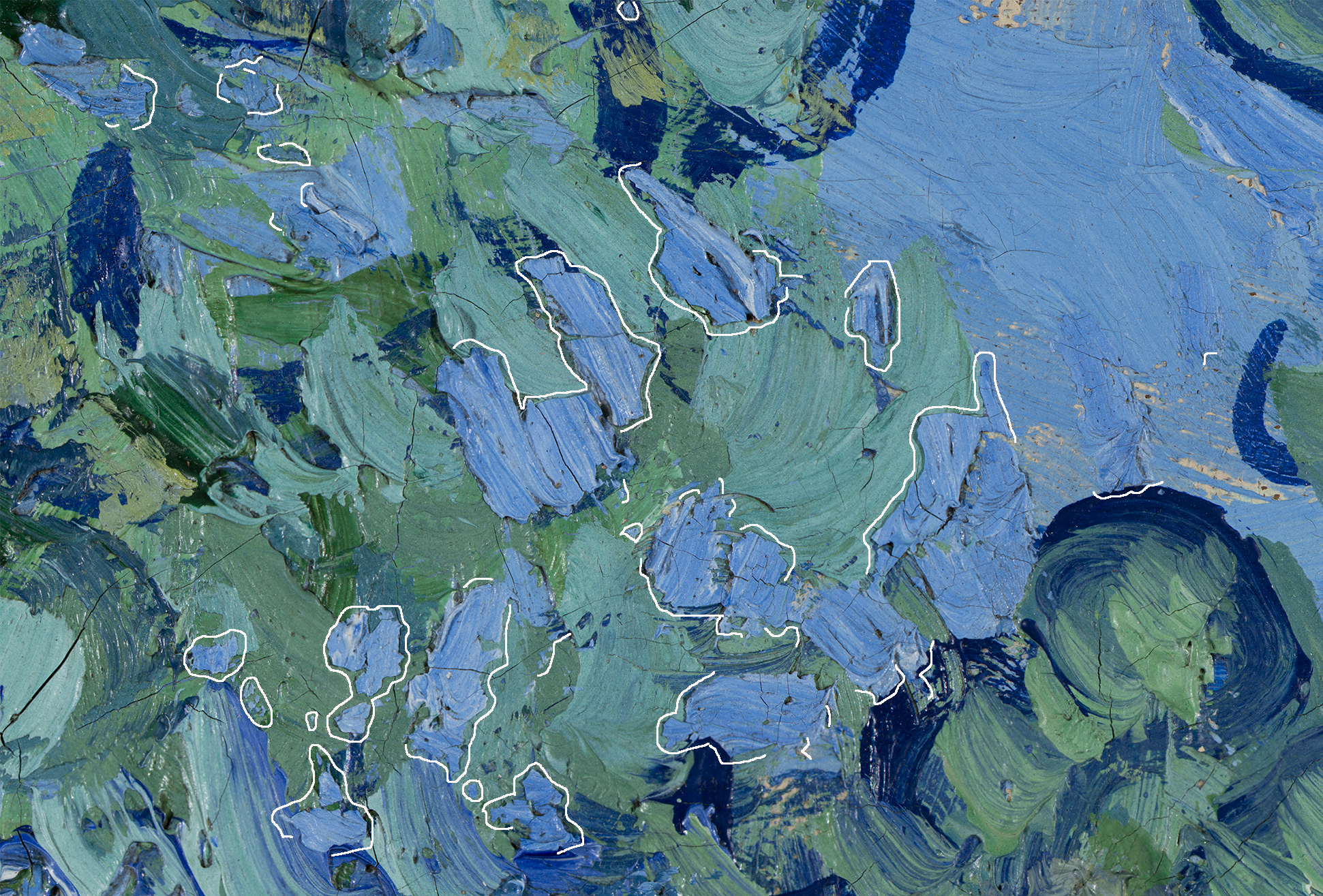

With a fresh supply of materials from his brother, Theo, Van Gogh started at least five paintings featuring olive trees in or around June 1889, including the Nelson-Atkins picture, which he painted on a commercially pre-primed, standard size 30 canvas.10See the accompanying technical entry by Schafer and Twilley. Verdant olive trees and a meandering path rendered in long, curving brushstrokes of gray-green and yellow are bordered by a brilliant row of red poppies. These elements invite viewers into the composition. The vertical wet-into-wet brushstrokes of the path are met by horizontal brushstrokes that articulate the ruggedness of the terrain beneath the trees (Fig. 11 in Conservation Technical Entry). In other areas of the composition, in particular at the far right in the trees (Fig. 17 in Conservation Technical Entry), Van Gogh applied short dabs of fresh yellow paint over longer strokes which had already dried. This is one indication that he painted the composition in two distinct sessions.11For further information on this aspect of Van Gogh’s painting, see the accompanying technical entry by Schafer and Twilley. Dappled spots of sunlight shine between the olive trees, making the heat of southern France feel almost palpable. Without painting the sun, Van Gogh transmitted its energy to his canvas.

The relationships between colors, and how they interact to intensify tones and create harmony, mood, and emotion, were essential to Van Gogh; he was particularly interested in the juxtaposition of complementary colors (red/green, blue/orange, violet/yellow). He learned about these pairings by looking at the work of Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) and reading Charles Blanc’s Grammaire des arts du dessin (1867).12The first color of each pair is a primary: red, yellow, and blue. Mixing them produces a secondary color: for example, red and blue make purple. That secondary color is complementary to the primary color that was not used in the mixture. Those primary and secondary colors, such as red and green, reinforce each other when juxtaposed. This phenomenon, known as the law of “simultaneous contrast,” was first described by the physicist Michel Eugène Chevreul in 1839 and practiced by the artist Eugène Delacroix. It had a tremendous impact on Van Gogh’s palette. See Charles Blanc, The Grammar of Painting and Engraving, trans. Kate Newell Doggett, 3rd ed. (1867; repr., New York, Hurd and Houghton, 1879). See also Michel Eugène Chevreul, The Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colours and their Applications to the Arts, trans. Charles Martel (1839; repr., London: Bell, 1916). Van Gogh cites Delacroix numerous times throughout his letters, referencing his interest in Delacroix’s use of color. Van Gogh wrote to Theo on April 18, 1885 (Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let494) and copied a passage out of Charles Blanc on Delacroix that ties these interests together. The passage Van Gogh copied comes from Blanc, Les artistes de mon temps, 64-66, 69, as cited in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let494, n10. Some of these color relationships appear in the Nelson-Atkins canvas: red poppies are set against or in close proximity to green foliage, and brilliant strokes of yellow/orange run alongside blue outlines of select trees.13Information on the specific pigments was obtained from Schafer and Twilley. See their accompanying technical entry for palette analysis. Seemingly missing in this group of complementary pairings, however, is violet and yellow.

Mapping Van Gogh’s palette in the Kansas City picture—tracking the locations where he used specific pigments—is essential for understanding the artist’s original intent. One of many findings through recent X-ray fluorescence spectrometry elemental mapping (MA-XRF), conducted by Mellon science advisor John Twilley and Nelson-Atkins paintings conservator Mary Schafer, revealed that the artist used a mixture of “geranium lake” and zinc white with cobalt and ultramarine blues in the shadows at the base of the olive trees. Because Van Gogh knew that geranium lake had a propensity to fade, he compensated by applying it in greater concentration.14Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Arles, on or about Wednesday, April 11, 1888, in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let595: “All the colors that Impressionism has made fashionable are unstable, all the more reason boldly to use them too raw, time will only soften them too much.” Original emphasis. This strategy, however, was not sufficient over the long term.15Geranium lake fades more completely when mixed with zinc white, as Van Gogh did at the base of the trees. See the accompanying technical entry by Schafer and Twilley. Only the blue and zinc white components remain visible, thus yielding blue shadows beneath the trees, where violet was intended to serve as a complement to the nearby yellowish orange strokes in the tree trunks.16The more extreme effect of fading occurs in the now mostly white mixtures of the foreground. These and other newly revealed complementary pairings, based on technical analyses of the painting, can be found in the accompanying technical entry by Schafer and Twilley. The discovery of the once-violet shadows connects the painting more firmly to a letter the artist wrote to his sister on June 16, 1889, about a landscape of an olive grove he had “just finished” with gray leaves, “their cast shadows violet on the sun-drenched sand.”17Ronald Pickvance was the first scholar to associate this letter with the Nelson-Atkins painting. See Ronald Pickvance, Van Gogh in Saint-Rémy and Auvers (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, and New York: Abrams, 1986), 293. See also the accompanying technical entry by Schafer and Twilley. Previously, many scholars believed the letter related to an olive tree study the artist painted in June of 1889 (National Gallery of Scotland) that the artist sent to his brother on consignment a month later.

The phrase “just finished” proves troubling.18Van Gogh felt the canvas was finished on June 16. He set it aside, having either rolled it or stacked it with other unstretched work while still somewhat wet, as evidenced by the presence of canvas weave impressions in the impasto. See accompanying technical entry. We know that Van Gogh was only allowed to paint outdoors in the first week of June, and this does not seem to allow enough time for him to have realized two successive campaigns of painting, with the earlier layers of paint left undisturbed and no evidence of intermixing of colors. In other words, evidence of wet-over-dry brushwork indicates that Van Gogh applied paint to the canvas again after it was dry (Fig. 14 in Conservation Technical Entry). While it is impossible to determine precisely how much time would be needed for the paint to dry between the artist’s initial campaign, begun no earlier than the first week of June, and a second campaign, it is highly unlikely this could have occurred by June 16, when he wrote the letter to his sister that he had “just finished” the picture. Determining when Van Gogh may have painted the second campaign of the Nelson-Atkins painting is critical to understanding how the picture fits within the Olive Tree series.

Many scholars argue that Van Gogh’s more stylized approach to the Olive Tree series, associated with the work he undertook in the fall of 1889, was in reaction to a group of imaginative religious paintings recently shared with him by Gauguin and Bernard.19In a letter sent to Émile Bernard on or about November 26, Van Gogh chastises him for his imaginative approach to his subject matter and advises him to start with nature. This is based on a number of religious compositions Bernard had recently shared with Van Gogh. In their respective object labels online, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Van Gogh Museum suggest that their fall Olive Tree paintings, with their stylized brushwork, are in response to Gauguin’s and Bernard’s recent compositions; however, these artists did not send their works to Van Gogh until well after he retouched the Nelson-Atkins composition with short, stippled brushwork. See https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/437998 (accessed August 24, 2020) and https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en/collection/s0045V1962 (accessed August 24, 2020). Vincent van Gogh to Émile Bernard, on or about November 26, 1889, in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let822. It is this author’s contention, however, that Van Gogh’s shift in thinking about approach started earlier. Van Gogh suffered a mental relapse between the first (summer) and second (fall) group of Olive Tree pictures. From July 16 until August 22, he could neither write nor paint. By September 5–6, he still had not set foot outside, but he was back at his easel “retouching some studies from this summer . . . with renewed clarity,” as he wrote to Theo.20Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, Thursday, September 5, to Friday, September 6, 1889, in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let800. This timing could work for a second campaign of paint on the Nelson-Atkins composition, allowing enough drying time for him to include it in the third group of paintings he sent to Theo (his art dealer as well as his brother) on September 28.21Van Gogh sent seven consignments to Theo during his time at Saint-Rémy. The first, on July 15, did not include the Kansas City painting. Scholars including Jansen, Luijten, and Bakker contend that while Van Gogh mentions sending an olive tree composition in this first batch of paintings, it was not a size 30 canvas and therefore could not have been the Nelson-Atkins composition. See Vincent van Gogh, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, to Theo van Gogh, Sunday, July 14, or Monday, July 15, 1889, in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let789. Van Gogh sent the next two batches to Theo in short succession on September 19 and September 28. While it is possible he included the Kansas City painting in the consignment on September 19, this would have only given the canvas a little less than two weeks of drying time, making it more plausible that he included it in the September 28 shipment. See the accompanying technical entry by Schafer and Twilley. Van Gogh’s period of reinvigoration came at the same moment he received an invitation to exhibit with Bernard and Les XX, a group of twenty avant-garde artists founded by attorney Octave Maus, in their next exhibition in Brussels.22He mentions this invitation in the same September 5–6 letter in which he talks about having renewed clarity (Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, September 5–6, 1889, in Jansen et., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let800). The exhibitions of Les XX also included a number of symbolist and Neo-Impressionist painters such as Theo van Rysselberghe (Belgian, 1862–1926), Maximilien Luce (1858–1941), Henri-Edmond Cross (1856–1910), and Georges Seurat (1859–1891), all of whom exhibited in the 1889 exhibition and many of whom painted in a pointillist style, with tiny dabs of pure color.23Theo van Rysselberghe met with Theo van Gogh in Paris in 1889, and Theo showed Van Rysselberghe many of Vincent’s paintings. This may have precipitated the invitation for Vincent to exhibit with Les XX the following year. See letter from Theo van Gogh to Vincent van Gogh, Paris, Tuesday, October 22, 1889, in which he mentions this meeting, in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let813. In that same letter of September 5–6, Van Gogh continued, “I would really like to exhibit there, while feeling my inferiority alongside so many Belgians who have an enormous amount of talent.”24Van Gogh singles out Belgian Symbolist painter Xavier Mellery (1845–1921), who he felt had an enormous amount of talent. Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, September 5–6, 1889, in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let800. A few days later, on September 10, he revealed to Theo how his newfound clarity affected his approach to painting, his brushwork in particular:

What a funny thing the touch is, the brushstroke. Out of doors, exposed to the wind, the sun, people’s curiosity, one works as one can, one fills one’s canvas regardless. Yet then one catches the true and the essential—that’s the most difficult thing. But when one returns to this study again after a time, and orders one’s brushstrokes in the direction of the objects—certainly it’s more harmonious and agreeable to see, and one adds to it whatever one has of serenity and smiles.25Vincent van Gogh, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, to Theo van Gogh, Tuesday, September 10, 1889, in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let801.

All of these ideas, along with the invitation in September to exhibit with Les XX (and his ensuing trepidation about it), were with him at the precise moment he returned to retouch the Nelson-Atkins picture, which includes many passages of short, stippled brushwork. Ordering his brushstrokes “in the direction of the objects,” while a continuation of his earlier approach that summer, became more definitive in the fall Olive Tree paintings. The final state of the Nelson-Atkins composition reflects the artist’s effort to work through these ideas well after initiating the project in early June. This positions the Kansas City picture as a transitional painting within the Olive Tree series, belonging more to the paintings he completed in the fall rather than the summer pictures.

Regardless of his approach in the Olive Trees series, Van Gogh found something eternal in the continuous rhythm of their twisted forms. His undulating brushstrokes of color make the soil come alive with the same energy that animates the branches rustling in the wind. The brushwork in the Nelson-Atkins painting, and in the Olive Tree series in general, communicates in a physical way the living force that Van Gogh found within the trees themselves.26For more on the dynamic force and spiritual essence that Van Gogh saw in trees, see Ralph Skea, Vincent’s Trees: Paintings and Drawings by Van Gogh (London: Thames and Hudson, 2013), 15; and Vincent van Gogh, Auvers-sur-Oise, to Joseph Isaäcson, May 25, 1890, in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/RM21/letter.html.

Notes

-

Vincent van Gogh to Émile Bernard, on or about Tuesday, October 8, 1889, in Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, no. b634 V/1962; published in Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker, eds., Vincent Van Gogh: The Letters, online edition (Amsterdam and The Hague: Van Gogh Museum and Huygens, 2009), http://vangoghletters.org/en/let809. All English translations are from this publication.

-

Eleven of these are on size 30 canvases, including the Nelson-Atkins painting.

-

Van Gogh read about the “ton rompu” (broken tone), the “ton vif” (strong tone) and “les tons voisins” (neighboring tones) in Charles Blanc’s essay on Delacroix: Charles Blanc, Les artistes de mon temps (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1876), 65, 69–71, as cited in Van Gogh’s letter to his brother Theo from mid-June 1884. See Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let450.

-

The initial inquiries into this question began with NAMA former associate curator of European painting Nicole Myers, paintings conservator Mary Schafer, and Mellon science advisor John Twilley.

-

In a letter to Theo in April 1889, Van Gogh remarked “Oh my dear Theo, if you saw the olive trees at this time. . . . It is something completely different from one’s idea of it in the North—it’s a thing of such delicacy—so refined. It is like the looped willows of our Dutch meadows . . . , that is to say, the rustle of an olive grove has something very intimate, something tremendously old about it.” Vincent van Gogh, Arles, to Theo van Gogh, April 28, 1889, in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let763.

-

Vincent van Gogh, Arles, to Theo van Gogh, September 21, 1888, in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let685.

-

Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, September 21, 1888, in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let685. See also Samantha Friedman, Van Gogh, Dalí, and Beyond: The World Reimagined, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2013), 15–17.

-

See Vincent van Gogh, Irises, 1889, oil on canvas, 29 1/4 x 37 1/8 in. (74.3 x 94.3 cm), J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; and Vincent van Gogh, Butterflies and Poppies, May–June 1889, oil on canvas, 13 3/4 x 10 in. (35 cm x 25.5 cm), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

-

One year before checking himself in at Saint-Rémy, Van Gogh referenced Émile Zola’s La Faute de l’Abbé Mouret, an 1875 novel about a monk who finds solace in an overgrown garden where a young woman nurses him back to health. This sheds light onto his interest in gardens and his belief in their restorative effect. Jennifer Helvey, Irises: Vincent van Gogh in the Garden (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Publications, 2009), 96.

-

See the accompanying technical entry by Schafer and Twilley.

-

For further information on this aspect of Van Gogh’s painting, see the accompanying technical entry by Schafer and Twilley.

-

The first color of each pair is a primary: red, yellow, and blue. Mixing them produces a secondary color: for example, red and blue make purple. That secondary color is complementary to the primary color that was not used in the mixture. Those primary and secondary colors, such as red and green, reinforce each other when juxtaposed. This phenomenon, known as the law of “simultaneous contrast,” was first described by the physicist Michel Eugène Chevreul in 1839 and practiced by the artist Eugène Delacroix. It had a tremendous impact on Van Gogh’s palette. See Charles Blanc, The Grammar of Painting and Engraving, trans. Kate Newell Doggett, 3rd ed. (1867; repr., New York, Hurd and Houghton, 1879). See also Michel Eugène Chevreul, The Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colours and their Applications to the Arts, trans. Charles Martel (1839; repr., London: Bell, 1916). Van Gogh cites Delacroix numerous times throughout his letters, referencing his interest in Delacroix’s use of color. Van Gogh wrote to Theo on April 18, 1885 (Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let494) and copied a passage out of Charles Blanc on Delacroix that ties these interests together. The passage Van Gogh copied comes from Blanc, Les artistes de mon temps, 64-66, 69, as cited in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let494, n10.

-

Information on the specific pigments was obtained from Schafer and Twilley. See their accompanying technical entry for palette analysis.

-

Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Arles, on or about Wednesday, April 11, 1888, in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let595: “All the colors that Impressionism has made fashionable are unstable, all the more reason boldly to use them too raw, time will only soften them too much.” Original emphasis.

-

Geranium lake fades more completely when mixed with zinc white, as Van Gogh did at the base of the trees. See the accompanying technical entry by Schafer and Twilley.

-

The more extreme effect of fading occurs in the now mostly white mixtures of the foreground. These and other newly revealed complementary pairings, based on technical analyses of the painting, can be found in the accompanying technical entry by Schafer and Twilley.

-

Ronald Pickvance was the first scholar to associate this letter with the Nelson-Atkins painting. See Ronald Pickvance, Van Gogh in Saint-Rémy and Auvers (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, and New York: Abrams, 1986), 293. See also the accompanying technical entry by Schafer and Twilley. Previously, many scholars believed the letter related to an olive tree study the artist painted in June of 1889 (National Gallery of Scotland) that the artist sent to his brother on consignment a month later.

-

Van Gogh felt the canvas was finished on June 16. He set it aside, having either rolled it or stacked it with other unstretched work while still somewhat wet, as evidenced by the presence of canvas weave impressions in the impasto. See accompanying technical entry.

-

In a letter sent to Émile Bernard on or about November 26, Van Gogh chastises him for his imaginative approach to his subject matter and advises him to start with nature. This is based on a number of religious compositions Bernard had recently shared with Van Gogh. In their respective object labels online, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Van Gogh Museum suggest that their fall Olive Tree paintings, with their stylized brushwork, are in response to Gauguin’s and Bernard’s recent compositions; however, these artists did not send their works to Van Gogh until well after he retouched the Nelson-Atkins composition with short, stippled brushwork. See https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/ 437998 (accessed August 24, 2020) and https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/en/collection/ s0045V1962 (accessed August 24, 2020). Vincent van Gogh to Émile Bernard, on or about November 26, 1889, in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let822.

-

Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, Thursday, September 5, to Friday, September 6, 1889, in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let800.

-

Van Gogh sent seven consignments to Theo during his time at Saint-Rémy. The first, on July 15, did not include the Kansas City painting. Scholars including Jansen, Luijten, and Bakker contend that while Van Gogh mentions sending an olive tree composition in this first batch of paintings, it was not a size 30 canvas and therefore could not have been the Nelson-Atkins composition. See Vincent van Gogh, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, to Theo van Gogh, Sunday, July 14, or Monday, July 15, 1889, in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let789. Van Gogh sent the next two batches to Theo in short succession on September 19 and September

-

While it is possible he included the Kansas City painting in the consignment on September 19, this would have only given the canvas a little less than two weeks of drying time, making it more plausible that he included it in the September 28 shipment. See the accompanying technical entry by Schafer and Twilley.

-

He mentions this invitation in the same September 5–6 letter in which he talks about having renewed clarity (Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, September 5–6, 1889, in Jansen et., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let800).

-

Theo van Rysselberghe met with Theo van Gogh in Paris in 1889, and Theo showed Van Rysselberghe many of Vincent’s paintings. This may have precipitated the invitation for Vincent to exhibit with Les XX the following year. See letter from Theo van Gogh to Vincent van Gogh, Paris, Tuesday, October 22, 1889, in which he mentions this meeting, in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let813.

-

Van Gogh singles out Belgian Symbolist painter Xavier Mellery (1845–1921), who he felt had an enormous amount of talent. Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, September 5–6, 1889, in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let800.

-

Vincent van Gogh, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, to Theo van Gogh, Tuesday, September 10, 1889, in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/en/let801.

-

For more on the dynamic force and spiritual essence that Van Gogh saw in trees, see Ralph Skea, Vincent’s Trees: Paintings and Drawings by Van Gogh (London: Thames and Hudson, 2013), 15; and Vincent van Gogh, Auvers-sur-Oise, to Joseph Isaäcson, May 25, 1890, in Jansen et al., Letters, http://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/RM21/letter.html.

-

The honor of the first goes to the Detroit Institute of Arts, with their 1922 acquisition of Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait in a Straw Hat (1887). For more on the history of the Van Gogh painting entering the Nelson-Atkins collection, see my introductory essay, “The Collecting of French Paintings in Kansas City,” in this publication.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Schafer and John Twilley, “Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June/September 1889,” technical entry in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.738.2088

MLA:

Schafer, Mary and John Twilley. “Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June/September 1889,” technical entry. French Paintings, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.738.2088.

Olive Trees was executed on a tightly woven, plain weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas that corresponds in size to a no. 30 figure standard-format supportstandard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format..1Anthea Callen, The Art of Impressionism: Painting Technique and the Making of Modernity (London: Yale University Press, 2000), 15. While painting in Saint Rémy, Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) would often cut a segment of primed canvas from a larger roll and attach it to a temporary, working frame. Any evidence for this process was removed with the tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. when the Nelson-Atkins painting was glue-linedlining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive., sometime prior to the 1932 acquisition. Paper now covers the outermost edges, and it is unclear if the current six-member stretcherstretcher: A wooden structure to which the painting’s canvas is attached. Unlike strainers, stretchers can be expanded slightly at the joints to improve canvas tension and avoid sagging due to humidity changes or aging. with mortise and tenon joins is original. The thin, off-white ground layerground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. was commercially applied using lead white containing small additions of both crushed natural barite and lithopone, colored by traces of silica and iron oxides (see Table 1).2The scientific study of Olive Trees was supported by an endowment from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for conservation science at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

Fig. 5. Detail of pale mint green layer beneath the foliage on the center left, Olive Trees (1889). Courtesy of R. Bruce North.

Fig. 5. Detail of pale mint green layer beneath the foliage on the center left, Olive Trees (1889). Courtesy of R. Bruce North.

Fig. 6. Detail of blue painted outlines in the upper trees and additions of light blue paint that expand areas of sky, Olive Trees (1889). Courtesy of R. Bruce North.

Fig. 6. Detail of blue painted outlines in the upper trees and additions of light blue paint that expand areas of sky, Olive Trees (1889). Courtesy of R. Bruce North.

Fig. 7. Element maps for cobalt (left) and iron (right). Detail of the central tree of Olive Trees (center). The elemental maps show the use of cobalt blue to define the central and right tree trunks in the early stages of painting, followed by final outlining strokes of Prussian blue that modify the central trunk.

Fig. 7. Element maps for cobalt (left) and iron (right). Detail of the central tree of Olive Trees (center). The elemental maps show the use of cobalt blue to define the central and right tree trunks in the early stages of painting, followed by final outlining strokes of Prussian blue that modify the central trunk.

Fig. 8. Element map for cobalt superimposed on that of zinc (lower left), showing the cobalt blue stroke that marks the lower left path

Fig. 8. Element map for cobalt superimposed on that of zinc (lower left), showing the cobalt blue stroke that marks the lower left path

Fig. 9. Detail of a red-violet stroke in the lower layers, visible beneath the blue-gray outline of a distant tree, Olive Trees (1889). Courtesy of R. Bruce North.

Fig. 9. Detail of a red-violet stroke in the lower layers, visible beneath the blue-gray outline of a distant tree, Olive Trees (1889). Courtesy of R. Bruce North.

Fig. 10. Detail of the energetic, curving paint strokes that make up the upper trees, Olive Trees (1889)

Fig. 10. Detail of the energetic, curving paint strokes that make up the upper trees, Olive Trees (1889)

Fig. 11. Detail of wet-over-wet paint applications in the vermilion poppies at the left edge of Olive Trees (1889). Courtesy of R. Bruce North.

Fig. 11. Detail of wet-over-wet paint applications in the vermilion poppies at the left edge of Olive Trees (1889). Courtesy of R. Bruce North.

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of plant material encased in paint, Olive Trees (1889)

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of plant material encased in paint, Olive Trees (1889)

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph of a grasshopper embedded in the paint of the foreground, Olive Trees (1889)

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph of a grasshopper embedded in the paint of the foreground, Olive Trees (1889)

Over the course of painting, Van Gogh made several modifications to the composition. He applied light blue paint on top of existing trees to add or expand areas of the sky, and the width of the lower right tree was cropped on its left side. Distant trees, located near the left horizon line and continuing toward the central trees, were reinforced and adjusted with gray-blue outlines, applied wet-over-drywet-over-dry: An oil painting technique that involves layering paint over an already dried layer, resulting in no intermixing of paint or disruption to the lower paint strokes. (Fig. 9).

Fig. 15. Detail of numerous paint losses among the right trees, Olive Trees (1889). Courtesy of R. Bruce North.

Fig. 15. Detail of numerous paint losses among the right trees, Olive Trees (1889). Courtesy of R. Bruce North.

Fig. 16. Photomicrograph of a paint loss and the gritty appearance of the second phase paint, Olive Trees (1889), 6x

Fig. 16. Photomicrograph of a paint loss and the gritty appearance of the second phase paint, Olive Trees (1889), 6x

Other significant artist changes occurred during a later stage of painting. Although Van Gogh began this landscape in June of 1889,6See the accompanying catalogue essay by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan. the presence of numerous wet-over-dry additions, paint losses, and a stylistic shift in Van Gogh’s brushwork suggest that Olive Trees was painted in two distinct sessions and completed in the fall.7The findings presented include those from an earlier 2012 study with curatorial contributions by Nicole R. Myers, former associate curator, European paintings and sculpture, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. These later additions had no effect on the impastoimpasto: A thick application of paint, often creating texture such as peaks and ridges. of the earlier paint strokes, indicating that the paint surface was solidly dry by the time Van Gogh returned to the canvas (Fig. 14). Poor adhesion between the first and second phase paint is also prevalent (Fig. 15), resulting in losses which expose underlying paint colors. Light-colored mixtures associated with the second phase paint are also characterized by a gritty texture (Fig. 16).8The underlying cause of this granular appearance has not been definitively identified. This distinctive texture is most prevalent among the lighter paint mixtures, and although zinc-fatty acid soap formations are widespread within the paints of both phases, the formations do not protrude through or disrupt the paint surface in those locations where they have been found inside samples. Zinc-fatty acid soaps, formed by reactions between zinc white and free fatty acids present in the oil paint, have been widely cited as a cause of adhesion loss between successive applications of oil paints based on zinc white, as in the case of Olive Trees. Crystalline zinc soaps have been found at the interface between the delaminating paint layers in various paintings based on zinc white. See for example L. Raven, M. Bisschoff, M. Leeuwestein, M. Geldof, J.J. Hermans, M. Stols-Witlox, and K. Keune, “Delamination Due to Zinc Soap Formation in an Oil Painting by Piet Mondrian (1872–1944): Conservation Issues and Possible Implications for Treatment,” in Metal Soaps in Art: Conservation and Research, ed. F. Casadio, K. Keune, P. Noble, A. Van Loon, E. Hendriks, S.A. Centeno, and G. Osmond (Springer Cultural Heritage Science Series, 2019), 343–58. While second phase painting in the foreground introduced additions of white, pale blue, yellow, and dark teal, there is no noticeable shift in brushwork from one phase to the next. In the trees, however, Van Gogh disrupted the long curving strokes with later dabs or dashes of paint, a manner of painting that resembles the tighter brushwork and smaller dabs of paint found among his later olive tree paintings produced in the fall of 1889 (Fig. 17).

Fig. 17. Detail of the lower right tree, showing the dabs of paint added in the second phase of painting, Olive Trees (1889). Courtesy of R. Bruce North.

Fig. 17. Detail of the lower right tree, showing the dabs of paint added in the second phase of painting, Olive Trees (1889). Courtesy of R. Bruce North.

Fig. 18. Photomicrograph of a weave impression made in the first phase paint, located in the shadow of the central tree, Olive Trees (1889)

Fig. 18. Photomicrograph of a weave impression made in the first phase paint, located in the shadow of the central tree, Olive Trees (1889)

Van Gogh’s palette for Olive Trees included geranium lake,11“Lake” pigment is produced by the combination of a soluble dye color with a soluble, usually colorless inorganic compound to produce a colored precipitate that can be handled like a dry pigment and thereafter combined with oil. In some cases, the precipitation was carried out in the presence of a colored carrier so that the dye precipitate coats a particle of another pigment. In 1889 eosin lakes of several varieties were available, including some that were precipitated on red lead for their combined color. However, Van Gogh employed the “geranium” lake whose color was solely that of its eosin content. Eosin was synthesized in 1871. See M.J. Depierre, “Note on the Application of Eosin,” American Chemist 6–7 (New York: C.F. & W. H. Chandler, 1875), 217. red lead oxide, vermilion, chrome yellow and chrome orange, viridian (hydrated chrome oxide), emerald green (copper acetoarsenite), synthetic ultramarine, cobalt blue, Prussian blue, and zinc white (see Table 1). Although his paint mixtures for works in the olive trees series incorporated both zinc white and lead white,12Kathryn A. Dooley, Annalisa Chieli, Aldo Romani, Stijn Legrand, Costanza Miliani, Koen Janssens, and John K. Delaney, “Molecular Fluorescence Imaging Spectroscopy for Mapping Low Concentrations of Red Lake Pigments: Van Gogh’s Painting The Olive Orchard,” Angewandte Chemie 59, no. 15 (April 6, 2020): 6046–53. he used zinc white almost exclusively in this case. Lead white occurrences are so finely dispersed as to suggest that it was a manufacturer’s additive in some of the tube colors, probably to enhance the drying of the oils with slow drying pigments, such as ultramarine. Calcite, gypsum, and white clay also occur as additives rather than primary white pigments. Charcoal is used very sparingly in drab greens. Several other pigments are notable for their absence. For example, cadmium yellow was not used, and yellow ocher is encountered only in very dilute yellow mixtures. Red lakes involving alizarin or carmine that he used in other works of the period were omitted.13Dooley et al., “Molecular Fluorescence Imaging Spectroscopy,” 6050. Tin and calcium associated with these lakes were not associated with the red lake in the Nelson-Atkins Olive Trees.

In addition to producing violet colors, geranium lake was added to blue-green mixtures to render them nearly black. However, it was not the sole means of producing violet shades in a painting that employed no violet pigments. Red lead, used sparingly in the painting, was mixed to produce dull violet and gray-violet shades that have not faded like those formulated with geranium lake. Often the red lead occurs in the tree trunks in combination with Prussian blue, a mixture that appears flatter, and more opaque, than the mixtures incorporating geranium lake with ultramarine or cobalt blue.

XRF mapping of individual elements offers insights into Van Gogh’s use of mixtures but often must be supplemented by other techniques such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM)scanning electron microscopy (SEM): Performed on a microsample of paint, the SEM provides a means of studying particle shapes beyond the magnification limits of the light microscope. This becomes increasingly important with the painting materials introduced in the early modern era, which are finer and more diverse than traditional artists’ materials. The SEM is routinely used in conjunction with an X-ray spectrometer, so that elemental identifications can be made selectively on the same minute scale as the electron beam producing the images. SEM methods are particularly valuable in studying unstable pigments, adverse interactions between incompatible pigments, and interactions between pigments and surrounding paint medium, all of which can have profound effects on the appearance of a painting., Raman spectroscopyRaman spectroscopy: A microanalytical technique applicable primarily to pigments and minerals, differentiating them based on both chemical bonding and crystal structure, often with extremely high sensitivity for individual particles. For example, traditional indigo and synthetic phthalocyanine blue are both carbon compounds not well differentiated by other methods utilized here, especially when used dilutely. However, they give unique Raman spectra. Calcium carbonates derived from chalk or pulverized oyster shell of identical chemical compositions can be differentiated based on their crystal structures (calcite and aragonite, respectively)., Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR): A broadly applicable microanalysis method for the identification of paint media classes such as oils, polysaccharides (gum arabic, etc.), proteins (glue and casein tempera), waxes (medium additions and restoration treatments), resins (varnish components), and synthetic media (restoration acrylics). FTIR is also very important for identifying pigments and fillers, and for differentiating closely-related compounds (e.g. neutral and basic lead carbonates, both of which may be found in lead white)., and polarized light microscopy (PLM)polarized light microscopy (PLM): A method used for the study and differentiation of pigments based on the optical properties of individual particles, including color, refractive index, birefringence, etc. PLM is particularly useful in identifying the presence of organic pigments such as indigo and Prussian blue, which often cannot be differentiated from paint medium in the scanning electron microscopy (SEM); differentiating synthetic pigments from their natural analogs by particle shape or the presence of extraneous mineral matter; and disclosing the presence of pigments with similar composition but differing color, such as red and yellow iron oxides. to differentiate pigments that either share the same elements or are not detectable by XRF mapping (see Table 1). Chromium is present in both chrome yellow and viridian, for example, and a lead response can originate from red lead, lead white, or chrome yellow. Ultramarine, a very important blue within the landscape, has no heavy elements and cannot be mapped under these conditions. PLM was particularly important in locating unfaded remnants of geranium lake.

Fig. 20. Photomicrograph of a vertical red stroke of pure geranium lake, Olive Trees (1889), 18x

Fig. 20. Photomicrograph of a vertical red stroke of pure geranium lake, Olive Trees (1889), 18x

Fig. 21. Dispersed geranium lake with minor lead white additions, transmitted light with crossed polars, 200x

Fig. 21. Dispersed geranium lake with minor lead white additions, transmitted light with crossed polars, 200x

Fig. 22. Detail of blue paint in the shadow to the right of the central tree, Olive Trees (1889)

Fig. 22. Detail of blue paint in the shadow to the right of the central tree, Olive Trees (1889)

Fig. 23. Dispersed pigments showing ultramarine and geranium lake in zinc white with traces of viridian, used in the shadow strokes in Fig. 22, transmitted light with crossed polars, 200x

Fig. 23. Dispersed pigments showing ultramarine and geranium lake in zinc white with traces of viridian, used in the shadow strokes in Fig. 22, transmitted light with crossed polars, 200x

Fig. 24. Photomicrograph of tree foliage on the lower right corner, Olive Trees (1889), 6x

Fig. 24. Photomicrograph of tree foliage on the lower right corner, Olive Trees (1889), 6x

Fig. 25. Partially dispersed pigment from the intense blue stroke in the foliage shown in Fig. 24, a mixture primarily of ultramarine and geranium lake with minor amounts of zinc white and viridian, transmitted light with crossed polars, 100x

Fig. 25. Partially dispersed pigment from the intense blue stroke in the foliage shown in Fig. 24, a mixture primarily of ultramarine and geranium lake with minor amounts of zinc white and viridian, transmitted light with crossed polars, 100x

Fig. 26. Elemental map for bromine, showing the distribution of geranium lake, both faded and unfaded, where it can be detected in amounts sufficient to differentiate from admixed pigments.

Fig. 26. Elemental map for bromine, showing the distribution of geranium lake, both faded and unfaded, where it can be detected in amounts sufficient to differentiate from admixed pigments.

Fig. 27. Detail of the lower right corner, Olive Trees (1889). A loss in the pale blue paint stroke exposes its original, unfaded pink interior.

Fig. 27. Detail of the lower right corner, Olive Trees (1889). A loss in the pale blue paint stroke exposes its original, unfaded pink interior.

Similarly, the blue shadows at the base of the olive trees were once violet in color, a detail that closely connects the Nelson-Atkins painting to a description in Van Gogh’s June 1889 letter: “I’ve just finished a landscape of an olive grove with gray foliage more or less like that of the willows, their cast shadows violet on the sun-drenched sand.”18Vincent van Gogh to Willemien van Gogh, June 16, 1889 in Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, no. b.712 V/1962; as cited in Jansen et al., Letters, http://www.vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let780/letter.html. These violet shadows would have heightened the yellow tonalities on the adjacent sun-splashed ground.

Fig. 29. Photomicrograph of rightmost trunk of the central tree, Olive Trees (1889), 12x

Fig. 29. Photomicrograph of rightmost trunk of the central tree, Olive Trees (1889), 12x

Fig. 30. Microsample of the gray paint protected by the overlapping orange stroke on the central tree trunk, revealing the unfaded, complementary violet color, reflected light, 200x

Fig. 30. Microsample of the gray paint protected by the overlapping orange stroke on the central tree trunk, revealing the unfaded, complementary violet color, reflected light, 200x

Notes

-

Anthea Callen, The Art of Impressionism: Painting Technique and the Making of Modernity (London: Yale University Press, 2000), 15.

-

The scientific study of Olive Trees was supported by an endowment from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for conservation science at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

-

No underdrawing was detected using magnified inspection or infrared imaging conducted in the infrared spectrum between wavelengths of 700 – 2200 nanometers.

-

X-ray fluorescence spectrometry elemental mapping was undertaken as part of a collaboration with the Laboratory of Molecular and Structural Archaeology, directed by Philippe Walter (CNRS/Pierre and Marie Curie University, Paris) by which their instrument design and operational software was provided to the authors.

-

The authors are grateful to paleo-entomologist, Dr. Michael S. Engel, senior curator and university distinguished professor, University of Kansas, and associate, American Museum of Natural History, NY. Dr. Engel determined that the disarticulated body fragments (head and hind leg) lodged in the wet paint of Olive Trees point to an already dead nymph or a shed exuvium. This fact prohibited the use of the annual seasonal cycle of grasshoppers in the region during 1889 to gain more specificity as to the months in which Van Gogh completed the landscape.

-

See the accompanying catalogue essay by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan.

-

The findings presented include those from an earlier 2012 study with curatorial contributions by Nicole R. Myers, former associate curator, European paintings and sculpture, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

-

The underlying cause of this granular appearance has not been definitively identified. This distinctive texture is most prevalent among the lighter paint mixtures, and although zinc-fatty acid soap formations are widespread within the paints of both phases, the formations do not protrude through or disrupt the paint surface in those locations where they have been found inside samples. Zinc-fatty acid soaps, formed by reactions between zinc white and free fatty acids present in the oil paint, have been widely cited as a cause of adhesion loss between successive applications of oil paints based on zinc white, as in the case of Olive Trees. Crystalline zinc soaps have been found at the interface between the delaminating paint layers in various paintings based on zinc white. See for example L. Raven, M. Bisschoff, M. Leeuwestein, M. Geldof, J.J. Hermans, M. Stols-Witlox, and K. Keune, “Delamination Due to Zinc Soap Formation in an Oil Painting by Piet Mondrian (1872–1944): Conservation Issues and Possible Implications for Treatment,” in Metal Soaps in Art: Conservation and Research, ed. F. Casadio, K. Keune, P. Noble, A. Van Loon, E. Hendriks, S.A. Centeno, and G. Osmond (Springer Cultural Heritage Science Series, 2019), 343–58.

-

Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, September 28, 1889, in Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, no. b656 V/1962; published in Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker, eds., Vincent van Gogh: The Letters (Amsterdam and The Hague: Van Gogh Museum and Huygens, 2009), no. 806, http://www.vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let806/letter.html. All English translations are from this publication. In footnote 8, the Nelson-Atkins painting is suggested to be the olive grove described in relation to this shipment.

-

A collaborative research project, led by the Dallas Art Museum and Van Gogh Museum, to study all fifteen paintings that comprise the olive tree series is underway and may clarify the chronology and shipment dates of the entire series. Nienke Bakker and Nicole R. Myers, eds., Van Gogh and the Olive Groves (Dallas: Dallas Museum of Art; Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, forthcoming).

-

“Lake” pigment is produced by the combination of a soluble dye color with a soluble, usually colorless inorganic compound to produce a colored precipitate that can be handled like a dry pigment and thereafter combined with oil. In some cases, the precipitation was carried out in the presence of a colored carrier so that the dye precipitate coats a particle of another pigment. In 1889 eosin lakes of several varieties were available, including some that were precipitated on red lead for their combined color. However, Van Gogh employed the “geranium” lake whose color was solely that of its eosin content. Eosin was synthesized in 1871. See M.J. Depierre, “Note on the Application of Eosin,” American Chemist 6–7 (New York: C.F. & W. H. Chandler, 1875), 217.

-

Kathryn A. Dooley, Annalisa Chieli, Aldo Romani, Stijn Legrand, Costanza Miliani, Koen Janssens, and John K. Delaney, “Molecular Fluorescence Imaging Spectroscopy for Mapping Low Concentrations of Red Lake Pigments: Van Gogh’s Painting The Olive Orchard,” Angewandte Chemie 59, no. 15 (April 6, 2020): 6046–53.

-

Dooley et al., “Molecular Fluorescence Imaging Spectroscopy,” 6050. Tin and calcium associated with these lakes were not associated with the red lake in the Nelson-Atkins Olive Trees.

-

Muriel Geldof, Matthijs de Keijzer, Maarten van Bommel, Kathrin Pilz, Johanna Salvant, Henk van Keulen, and Luc Megens, “Van Gogh’s Geranium Lake,” in Van Gogh’s Studio Practice, ed. Marije Vellekoop, Muriel Geldof, Ella Hendriks, Leo Jansen, and Alberto de Tagle (Brussels: Mercatorfonds, 2013), 285–86.

-

All references to specific pigments are based on identification from samples that were examined in the scanning electron microscope, supported with elemental analysis by X-ray spectrometry. Polarized light microscopy was used to screen for compounds not responsive to other tests and to correlate colors to the proportions of mixtures. Confirmatory pigment identifications were carried out with Raman spectroscopy and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy.

-

Eosin is a water-soluble, synthetic dye invented in 1871 and soon after adapted to painting use in the form of a “lake” pigment of which there were several varieties. The variety found in Olive Trees contains eosin bound to aluminum ions derived from an alum solution. See A. Baeyer, “Ueber eine neue Klasse von Farbstoffen,” Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft 4, no. 2 (1871): 555–58; M. J. Depierre,“Note on the Application of Eosin,” 217; A. H. Allen, Commercial Organic Analysis, 2nd ed., vol. 3, part 1 (Philadelphia: P. Blakiston, Son, 1889), 167–73. This “geranium” lake can be markedly faded by light exposure, a detrimental trait already known when employed by Van Gogh. By 1900 its short-lived commercial success was already being referred to in the past tense. See F. H. Jennison, The Manufacture of Lake Pigments from Artificial Colours (London: Scott, Greenwood & Son; New York: Van Nostrand, 1900).

-

See the accompanying catalogue essay by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan. For an overview of Van Gogh’s experimentation with color, see Maite van Dijk, “Van Gogh and the Laws of Colour: An Introduction,” in Van Gogh’s Studio Practice, 216–25.

-

Vincent van Gogh to Willemien van Gogh, June 16, 1889 in Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, no. b.712 V/1962; as cited in Jansen et al., Letters, http://www.vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let780/letter.html.

-

Scott Heffley, December 8, 2005, treatment report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, no. 32-2.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan Gray, “Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June/September 1889,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.738.4033

MLA:

Gray, Meghan. “Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June/September 1889,” documentation. French Paintings, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.738.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan Gray, “Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June/September 1889,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.738.4033

MLA:

Gray, Meghan. “Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June/September 1889,” documentation. French Paintings, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.738.4033.

With the artist, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, France, until September 20 or 28, 1889 [1];

To his brother, Theo van Gogh (1857–1891), Paris, 1889–January 25, 1891 [2];

Inherited by his widow, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger (1862–1925), Bussum and Amsterdam, The Netherlands, stock no. 147, as Oliviers /30/effet du matin, 1891–May 25/June 1905 [3];

Purchased from Bonger by Kunstsalon Paul Cassirer, Berlin, stock no. 6588, as Olivenbaume, May 25/June 1905 [4];

Purchased from Cassirer by Carl Moll (1861–1945) for the Galerie H. O. Miethke, Vienna, May 25, 1905–at least January 1906 [5];

Purchased from the Galerie Miethke by Baron Adolf Kohner (1865/6–1937), Budapest, inventory no. K. 27, as Olajerdő, by April 24, 1910–October 7, 1930 [6];

[Possibly purchased from Kohner by] Paul Rosenberg and Co., Inc., Paris, London, and New York, no. 2854, as Les oliviers, by October 7, 1930–January 23, 1932 [7];

Purchased half-share from Rosenberg by Durand-Ruel, Paris, for Durand-Ruel, New York, stock no. 5169, as Les Oliviers, October 7, 1930–January 23, 1932 [8];

Purchased remainder of share from Rosenberg by Durand-Ruel, New York, January 23, 1932 [9];

Purchased from Durand-Ruel, through Harold Woodbury Parsons and Effie Seachrest, by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1932 [10].

Notes

[1] The artist may have sent the painting to his brother and dealer on or about September 20 or more likely on September 28, 1889. Letters from Vincent van Gogh, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, to his brother, Theo van Gogh, on or about September 20, 1889, and September 28, 1889, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, inv. nos. b655 a-b V/1962 and b656 V/1962; pub. in Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker, eds., Vincent Van Gogh: The Letters; The Complete Illustrated and Annotated Edition, vol. 5 (London: Thames and Hudson, 2009), letter nos. 805 and 806, pp. 100–11.

[2] Van Gogh viewed the consignments of paintings he sent to his brother and dealer, Theo van Gogh, as remuneration for the latter’s financial support. Letter from Vincent van Gogh, Nuenen, to his brother, Theo van Gogh, on or about March 20, 1884, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, inv. nos. b398 V/1962 (sheet 1) and b397 d V/1962 (sheet 2); pub. in Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker, eds., Vincent Van Gogh: The Letters; The Complete Illustrated and Annotated Edition, vol. 3 (London: Thames and Hudson, 2009), letter no. 440, pp. 138–40.

[3] Although, formally speaking, Vincent Willem van Gogh (1890–1978) was joint owner of the Van Gogh collection from 1891, his mother, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, managed the collection until her death in 1925. See the inventory of van Gogh’s works then in van Gogh-Bonger’s collection, Andries Bonger, “Catalogue des œuvres de Vincent van Gogh,” 1891, Brieven en Documenten, b 3055 V/1962 (document),Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, no. 147, as Oliviers /30/effet du matin. For the Cassirer exhibition, see Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, “List of 30 titles and prices of paintings by Vincent van Gogh, made for Cassirer, April 1905,” Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Brieven en Documenten, 1905 b 2185 V/1982 (document, inkt, potlood, papier), no. 14-147, as Olijfbomen. Cassirer records the purchase of the canvas from Johanna on May 25, 1905 [see note 4], but Johanna records the sale of the canvas to Cassirer in her account book for the month of June 1905; see Theo van Gogh and Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, “Account book of Theo van Gogh and Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, May 21 1889–January 25, 1925,” Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Brieven en Documenten, b 2205 V/1982 (boek, inkt op papier), p. 14 line no. 10, stock no. 4, as Olijven, and p. 89 line no. 21, as “ontvangen van Paul Cassirer te Berlijn voor 8 gr. En 1 kl. schilderij.” Copies in NAMA curatorial files.

[4] See Kunstsalon Paul Cassirer Berlin, Einkaufsbücher (3) 1903–1919 [book of purchases], May 25, 1905, Paul Cassirer-Walter Feilchenfeldt Archiv, Zurich, p. 44, stock no. 6588, as Olivenbäume. Kunstsalon Paul Cassirer Berlin, Verkaufsbuch (1) October 2, 1903–April 28, 1910 [stock book of sales], May 1905, Paul Cassirer-Walter Feilchenfeldt Archiv, Zurich, p. 102?, stock no. 6588?.

[5] Call Moll was the artistic director of Galerie H. O. Miethke from 1904–1912.

[6] According to the verso of Kohner’s stock card (in a private collection, Hungary), the painting was “Vétetett a bécsi Galerie Miethke-cégtől.” We take this to mean that Kohner bought the painting from Galerie Miethke in Vienna. See correspondence from Péter Molnos, art historian, Budapest, to Meghan Gray, NAMA, October 4, 2017, NAMA curatorial file. See also inventory case K. 27, inventory loose card reproduced in Judit Geskó, ed., Van Gogh in Budapest, exh. cat. (Budapest: Museum of Fine Arts, 2006), 149. Kohner was a regular patron of Galerie Miethke and sold his Old Master collection in March 1908 in order to collect modern artists.

Kohner’s birthdate is unclear: The year 1866 is given in Péter Molnos, Lost Heritage: Hungarian Art Collectors in the Twentieth Century (Budapest: Kieselbach Gallery and Auction House, 2018), 92; the year 1865 is given in Ilona Sármány-Parsons, “Notes on Patronage of Modernism in the Fine Arts in Vienna and Budapest at the Turn of the Century,” CEU History Department Yearbook (1993): 151.

In his 1928 catalogue raisonné, J. B. de la Faille erroneously lists Galerie d’Art Barbazanges, Paris, as a constituent, an error that has persisted in other catalogues. See L’Œuvre de Vincent Van Gogh: Catalogue Raisonné (Paris: Éditions G. Van Oest, 1928), no. 715, pp. 1:203. The Galerie operated from ca. 1910/1911 until ca. 1929, during the time that Adolf Kohner is documented to have owned the painting.

[7] According to Péter Molnos, the painting was exported from Budapest on October 8, 1930, and was likely sent to Paul Rosenberg in Paris. See Péter Molnos, Aranykorok Romjain: Tanulmányok A Modern Magyar Festészet és Műgyűjtés Történetéből a Kieselbach Galéria Alapításának Huszadik Évfordulójá (Budapest: Kieselbach Galéria Kereskedelmi Kft., 2015), 107. See also no. 362, Central Archives, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, list of items exported from Budapest, no. 1930/ 3-23., 8 October 1930. Thanks to Péter Molnos for providing a scan of this document, which says, “Bejelentése alapján / K. föigazgató ni. 362. Dr. Kohner Adolf br. (Damjanich-n. / 20.) Izignálatlan Van Gogh-féle Olajerdő / c. festményre (Franciaországba ?) x/8”. See The Paul Rosenberg Archives, a Gift of Elaine and Alexandre Rosenberg, III.D, Rosenberg Galleries: Miniature Photo and Card Index, ca. 1910–1987, and IV.A.I.a, Liste de Photographies, Paris, [1917–1939] [1940–present], The Museum of Modern Art, New York. According to Ilda François, secretary to Elaine Rosenberg, Paul Rosenberg must have purchased the painting between June 1929 and November 1930; the exact purchase date is unknown. See also email from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie., Paris, to Nicole Myers, NAMA, January 11, 2016, NAMA curatorial file. Durand-Ruel says that Rosenberg purchased the painting for 104,000 Pengos, which was the official Hungarian currency; therefore it is possible that Rosenberg purchased the painting directly from Kohner.

[8] See email from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie., Paris, to Nicole Myers, NAMA, January 11, 2016, NAMA curatorial file. Durand-Ruel erroneously records the purchase of the painting by the Kansas City Art Institute. Actually, the painting was sent on approval to NAMA from March 18, 1931 until its purchase in January 1932, where it was placed on view at the Kansas City Art Institute since the museum was not yet built. At this time, a petition spearheaded by local dealer Effie Seachrest (1869–1952) was signed by about 135 people encouraging the museum to purchase the work. See “Petition to purchase Van Gogh Olive Orchards,” ca. April 21, 1931, NAMA Archives, William Rockhill Nelson Trust Office Records (RG 80/05), Series II: Objects Offered, 1926–33, box 7, folder 12, Durand-Ruel, 1931–32; and letter from J. C. Nichols to Sybil Brelsford, July 21, 1931, NAMA Archives, William Rockhill Nelson Trust Office Records (RG 80/05), Series I: General Correspondence and Records, 1926–33, box 6, folder 21, University Trustees 1931, f. 2. See also “Pictures remaining in the Art Institute after May 20, 1932,” May 20, 1932, NAMA Archives, William Rockhill Nelson Trust Office Records 1926–33, RG 80/05, Series I, box 02, folder 17, Exhibition at the Kansas City Art Institute, 1932.

[9] See email from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie., Paris, to Meghan Gray, NAMA, February 5, 2016, NAMA curatorial file.

[10] “The offer [to Durand-Ruel] was made in answer to petitions to the Trustees signed by at least two hundred admirers urging the purchase of this picture” [see footnote 8]. See “University Trustees Meeting Minutes,” January 12, 1932, NAMA Archives, William Rockhill Nelson Trust Office Records (RG 80/05), Series I: General Correspondence and Records, 1926–33, box 6, folder 20, University Trustees 1932.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan Gray, “Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June/September 1889,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.738.4033

MLA:

Gray, Meghan. “Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June/September 1889,” documentation. French Paintings, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.738.4033.

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Grove, June 1889, oil in canvas, 28 3/8 x 36 1/4 in. (72 x 92 cm), Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo.

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Grove, June 1889, oil on canvas, 17 3/8 x 23 1/4 in. (44 x 59 in.), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Vincent van Gogh, The Olive Trees, June-July, 1889, oil on canvas, 28 5/8 x 36 in. (72.6 x 91.4 cm), Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Orchard, September 1889, oil on canvas, 21 1/4 x 25 5/8 in. (53.5 x 64.5 cm), private collection, Switzerland.

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, November 1889, oil on canvas, 28 5/8 x 36 1/4 in. (72.7 x 92.1 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, November 1889, oil on canvas, 19 1/4 x 24 3/4 in. (51 x 65.2 cm), National Galleries Scotland, Edinburgh.

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Grove, Saint-Rémy, second half of November 1889, oil on canvas, 29 1/8 x 36 5/8 in. (74 x 93 cm), Göteborgs Konstmuseum, Göteborg, Sweden.

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, second half of November 1889, oil on canvas, 29 x 36 1/2 in. (73.7 x 92.7 cm), The Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Grove, November–December 1889, oil on canvas, 28 5/8 x 36 5/8 in. (73 x 92.5 cm), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees on a Hillside, November–December 1889, oil on canvas, 13 x 15 3/4 in. (33 x 40 cm), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Grove with Two Olive Pickers, December 1889, oil on canvas, 28 3/4 x 36 1/4 in. (73 x 92 cm), Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo.

Vincent van Gogh, Women Picking Olives, December 15–20, 1889, oil on canvas, 28 3/4 x 35 in. (73 x 89 cm), Basil P. and Elise Goulandris, Lausanne.

Vincent van Gogh, Women Picking Olives, ca. December 20, 1889, oil on canvas, 28 5/8 x 36 in. (72.7 x 91.4 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Vincent van Gogh, The Olive Orchard, ca. December 20, 1889, oil on canvas, 28 3/4 × 36 1/4 in. (73 × 92 cm ), National Gallery of Art, Washington DC.

Preparatory Works

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan Gray, “Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June/September 1889,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.738.4033

MLA:

Gray, Meghan. “Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June/September 1889,” documentation. French Paintings, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.738.4033.

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Grove, June 1889, reed pen and brown ink on paper, 19 5/8 x 25 5/8 in. (50 x 65 cm), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees in a Mountain Landscape, second half of June 1889, pencil, pen, and reed pen on paper, 18 1/2 x 24 5/8 in. (47 x 62.5 cm), Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees with the Alpilles in the Background, before June 18, 1889, reed pen, brush and black and brown inks over black graphite on bluish laid paper, 9 5/8 x 15 9/16 in. (24.5 x 39.5 cm), Private Collection, France.

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees with the Alpilles in the Background, June 17 or 18, 1889, black chalk, brush, brown ink on paper, 19 5/8 x 25 5/8 in. (50 x 65 cm), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Vincent van Gogh Three Olive Trees with the Alpilles and Rising Sun I, October–November 1889, reed pen and brown ink on bluish laid paper, 9 5/8 x 15 9/16 in. (24.5 x 39.5 cm), Private Collection, France.

Vincent van Gogh, Three Olive Trees with the Alpilles and Rising Sun II, October–November 1889, reed pen and brown ink on bluish laid paper, 9 11/16 x 15 9/16 in. (24.6 x 39.5 cm), Private Collection, France.

Vincent van Gogh, Three Olive Trees with the Alpilles and Rising Sun III, October–November 1889, reed pen and brown ink on bluish laid paper, 9 5/8 x 15 9/16 in. (24.5 x 39.5 cm), Private Collection, France.

Vincent van Gogh, Olive Grove with Four Pickers, December 1889, reed pen and brown ink on bluish laid paper, 9 11/16 x 15 9/16 in. (24.6 x 39.5 cm), Private collection, France.

Vincent van Gogh, Women Picking Olives, May–June 1890, pencil on paper, 5 1/4 x 3 3/8 in. (13.4 x 8.5 cm), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan Gray, “Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June/September 1889,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.738.4033

MLA:

Gray, Meghan. “Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June/September 1889,” documentation. French Paintings, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.738.4033.

Possibly paintings by Vincent van Gogh, Theo van Gogh’s apartment, 8, Cité Pigalle, Paris, end of 1890.

Vincent Van Gogh, Museum van Oudheden, Groningen, Netherlands, February 21–26, 1896, no. 40, as Oliviers.

van Gogh exhibition, Galerie Vollard, Paris, ca. December 1896–February 1897, no cat., no. 21, as Jardin des Oliviers.

VII. Jahrgang Frühjahr 1905: VII. Ausstellung, Galerie Paul Cassirer, Berlin, April 29–ca. May 25, 1905, no. 23, as Olivenbäume.

Vincent van Gogh: Kollektiv-Ausstellung, Galerie H. O. Miethke, Vienna, January 6–31, 1906, no. 44, as Olivenhain.

Internationalen Kunstschau, Vienna, May–October 1909, room 14, no. 2, as Olivenhain.

Művészház nemzetközi impresszionista kiállításához, Művészház, Budapest, April 24–June 19, 1910, room 7, no. 4, as Oliva-erdő.

Die Neue Kunst, Galerie Miethke, Vienna, January–February 9, 1913, no. 19, as Olivenbäume.

A Köztulajdonba vett Műkincsek Elsö Kiállitása, Műcsarnok, Budapest, May–July 1919, room 6, no. 7, as Olajerdö.

One Hundred Years of French Painting 1820–1920, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, March 31–April 28, 1935, no. 64, as The Olive Grove.

Possibly Vincent Van Gogh, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 12–July 10, 1936, hors cat., as Olive Grove.

The Art and Life of Vincent van Gogh: A Loan Exhibition in Aid of American and Dutch War Relief, Wildenstein, New York, October 6–November 7, 1943, no. 48, as The Olive Trees.

Paintings by Vincent Van Gogh, John Herron Museum of Art, Indianapolis, November 14–December 12, 1943, hors cat.

Loan Exhibition of Great Paintings: Five Centuries of Dutch Art [Exposition de Tableaux Célèbres: Cinq Siècles d’Art Hollandais], Art Association of Montreal, Canada, March 9–April 9, 1944, no. 129, as The Olive Trees, Les Oliviers.

Revolutionaries in Art: 1846–1946, Denver Art Museum, November 8–30, 1946, no cat.

A Loan Exhibition of Six Masters of Post-Impressionism: Benefit of Girl Scout Council of Greater New York, Wildenstein, New York, April 8–May 8, 1948, no. 67, as The Olive Grove.

Work by Vincent Van Gogh, Cleveland Museum of Art, November 3–December 12, 1948, no. 22, as The Olive Trees (Les Oliviers).

Twentieth Anniversary Exhibition: The Beginnings of Modern Painting, France 1800–1910, Joslyn Memorial Art Museum, Omaha, NE, October 4–November 4, 1951, unnumbered, as The Olive Grove.

Twenty Years of Collecting, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 11–31, 1953, no cat.

Painters’ Painters, Buffalo Fine Arts Academy, Albright Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY, April 16–May 30, 1954, no. 29, as The Olive Grove.

Van Gogh: Loan Exhibition For the Benefit of The Public Education Association, Wildenstein, New York, March 24–April 30, 1955, no. 51, as The Olive Trees.

Possibly Cubists, Fauves, and Impressionists, Denver Art Museum, October 1–November 18, 1956, no cat.

Vincent Van Gogh: A Loan Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings, Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery, July 3–August 4, 1957, no. 14, as The Olive Trees.

An Inaugural Exhibition: El Greco, Rembrandt, Goya, Cézanne, Van Gogh, Picasso, Milwaukee Art Institute, September 12–October 20, 1957, no. 79, as Olive Grove.

Twenty–fifth Anniversary Exhibition, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 1958, hors cat.

The Logic of Modern Art: An Exhibition Tracing the Evolution of Modern Painting from Cezanne to 1960, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, January 19–February 26, 1961, no. 7, as The Olive Grove.

Homage to Effie Seachrest, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, August 25–October 9, 1966, no. 10, as The Olive Grove.

Vincent van Gogh Exhibition, The National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo, October 12–December 8, 1985; Nagoya-City Museum, December 19, 1985–February 2, 1986, no. 82, as Olive Orchard.

Van Gogh in Saint-Rémy and Auvers, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, November 25, 1986–March 22, 1987, no. 12, as Olive Orchard.

Impressionism: Selections from Five American Museums, The Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, November 4–December 31, 1989; The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, January 27–March 25, 1990; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, April 21–June 17, 1990; The Saint Louis Art Museum, July 14–September 9, 1990; The Toledo Museum of Art, September 30–November 25, 1990, no. 36, as Olive Orchard.

Vincent van Gogh and the Painters of the Petit Boulevard, The Saint Louis Art Museum, February 17–May 13, 2001; Städelsches Kunstinstitut und Städtische Galerie, Frankfurt, June 8–September 2, 2001, unnumbered, as Olive Orchard.

l’Oro e l’Azzurro: I colori del Sud da Cézanne a Bonnard, Casa dei Carraresi, Treviso, October 10, 2003–March 7, 2004, no. 23, as Ulivi.

Gauguin and the Origins of Symbolism, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, September 28, 2004–January 9, 2005, no. 70, as Olive Grove [Les oliviers].

Van Gogh: Heartfelt Lines, Albertina, Vienna, September 5–December 8, 2008, no. 115, as Olive Orchard.

Vincent Van Gogh: Between Earth and Heaven; The Landscapes, Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland, April 26–September 27, 2009, no. 51, as Olive Orchard.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan Gray, “Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June/September 1889,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.738.4033

MLA:

Gray, Meghan. “Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, June/September 1889,” documentation. French Paintings, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.738.4033.

Possibly Frederik van Eeden, “Kunst: Vincent van Gogh,” De Nieuwe Gids, year 6, vol. 1, issue 2 (December 1890): 268–69 [repr. in Frederik van Eeden, Studies, tweede reeks (Amsterdam: W. Versluys, 1894), 107].

Vincent van Gogh, exh. cat. ([Groningen: Museum van Oudheden], 1896), 2, as Oliviers.

VII. Jahrgang Frühjahr 1905: VII. Ausstellung, exh. cat. (Berlin: Paul Cassirer, 1905), unpaginated, as Olivenbäume.

E[gbert] D[elpy], “Salon Cassirer,” Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger, no. 233 (May 16, 1905), as Olivenbäume.

August Endell, “Vincent van Gogh,” Freistatt, no. 24 (June 17, 1905): 379, as Olivenwald [repr. in Susan Alyson Stein, ed., Van Gogh: A Retrospective (New York: Hugh Lauter Levin Associates, 1986), 331].

Hugo von Habermann, Vincent van Gogh: Kollektiv-Ausstellung, exh. cat. (Vienna: Galerie H. O. Miethke, 1906), 15, as Olivenhain.

L[udwig] H[eves]i, “Aus dem Wiener kunstleben: Vincent van Gogh; Die Scholle,” Pester Lloyd, no. 15 (January 18, 1906): 5, as Olivenhain.

Ludwig Hevesi, Altkunst-Neukunst: Wien 1894–1908 (1909; repr., Klagenfurt, Austria: Ritter Verlag, 1986), 527–29, as Olivenhain.

Katalog der Internationalen Kunstschau Wien 1909, exh. cat. (Vienna: Arbeitsausschuss der Internationalen Kunstschau, 1909), 27, as Olivenhain.

Miklós Rózsa, ed., Kalauz a Művészház nemzetközi impresszionista kiállításához, exh. cat. (Budapest: Művészház, 1910), 51, (repro.), as Oliva-erdő.

h. ö, “Budapesti magángyűjtemények. I. Dr. Kohner Adolf [Private Collections in Budapest. I. Dr. Adolf Kohner],” Pesti Napló (April 22, 1910): 12, as Tájkép [repr., Péter Molnos, Lost Heritage: Hungarian Art colelctors in the Twentieth Century (Budapest: Kieselbach Gallery and Auction House, 2018), 136, as Landscape].

Simon Meller, “Kohner Adolf Művészeti Gyűjteménye,” Vasárnapi Ujság 58, no. 18 (April 30, 1911): 354, 363, (repro.), as olivaerdejével.